Logogram

Non-logographic writing systems, such as alphabets and syllabaries, are phonemic: their individual symbols represent sounds directly and lack any inherent meaning.[1][2] All logographic scripts ever used for natural languages rely on the rebus principle to extend a relatively limited set of logograms: A subset of characters is used for their phonetic values, either consonantal or syllabic.[citation needed] All historical logographic systems include a phonetic dimension, as it is impractical to have a separate basic character for every word or morpheme in a language.In the case of Chinese, the vast majority of characters are a fixed combination of a radical that indicates its nominal category, plus a phonetic to give an idea of the pronunciation.Due to the long period of language evolution, such component "hints" within characters as provided by the radical-phonetic compounds are sometimes useless and may be misleading in modern usage.Specifically, reaction times were shorter when participants were presented with a phonologically related picture before being asked to read a target character out loud.Instead, the authors hypothesize that the difference in latency times is due to additional processing costs in Japanese, where the reader cannot rely solely on a direct orthography-to-phonology route, but information on a lexical-syntactical level must also be accessed in order to choose the correct pronunciation.This hypothesis is confirmed by studies finding that Japanese Alzheimer's disease patients whose comprehension of characters had deteriorated still could read the words out loud with no particular difficulty.Therefore, in China, Vietnam, Korea, and Japan before modern times, communication by writing (筆談) was the norm of East Asian international trade and diplomacy using Classical Chinese.Conversely, a phonetic character set is written precisely as it is spoken, but with the disadvantage that slight pronunciation differences introduce ambiguities.Many alphabetic systems such as those of Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, and Finnish make the practical compromise of standardizing how words are written while maintaining a nearly one-to-one relation between characters and sounds.Orthographies in some other languages, such as English, French, Thai and Tibetan, are all more complicated than that; character combinations are often pronounced in multiple ways, usually depending on their history.Hangul, the Korean language's writing system, is an example of an alphabetic script that was designed to replace the logogrammatic hanja in order to increase literacy.

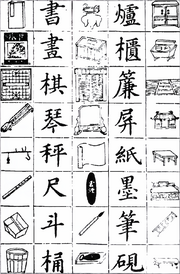

Logography (printing)lexicographywritten languageAncient Greekwritten charactersemanticmorphemeChinese charactersChineseEgyptian hieroglyphscuneiform scriptwriting systemalphabetssyllabariesrebus principleideographsnatural languageshieroglyphsdeterminativesradicalhieraticdemoticAncient EgyptiangraphemesAnatolian hieroglyphsCretan hieroglyphsLinear ALinear BMaya scriptAztec scriptMixtec scriptBamum scriptPahlavi scriptsAramaicMiddle PersianSassanid periodhozwārishnheterogramsArab conquest of PersiavariantArabic alphabetDeterminativeideogramChinese character classificationhànzìpictogramsideogramsconceptsorthographicJapaneseOld ChineseMiddle ChineseobstruentspalatalizationpharyngealizationStandard MandarinWilliam H. BaxterLaurent Sagartsound changesmorphographiclanguage processingAlzheimer's diseaselexical decision tasksvarieties of ChineseStandard Chinese筆談East AsianClassical ChineseItalianSpanishFinnishEnglishFrenchTibetanHangulKorean languagePeople's Republic of ChinaChart of Common Characters of Modern ChineseChart of Standard Forms of Common National CharactersRepublic of ChinaList of Graphemes of Commonly-Used Chinese CharactersHong Kongelementaryjunior secondaryinput methodsCangjieWubi methodsBopomofoPinyinISO 8859Basic Multilingual PlaneVariable-width encodingsUnicodeDongba symbolsSymbolSyllabogramWingdingsSitelen PonaconstructedBaxter, William H.Sagart, LaurentÉcole des Hautes Études en Sciences SocialesDeFrancis, JohnWriting systemsIndex of language articlesLanguageHistory of writingHistory of the alphabetScripts in Unicodeby first written accountAncient languages corpuses by sizeUndeciphered writing systemsCreators of writing systemsAbjadsAbugidasFeaturalIdeogrammicNumeralPhonogrammicPictographicSemi-syllabariesShorthandArabicCanadian syllabicsDevanagariMongolian