Bulgarian Orthodox Church

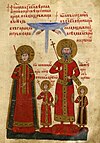

Towns such as Serdica (Sofia), Philipopolis (Plovdiv), Odessus (Varna), Dorostorum (Silistra) and Adrianople (Edirne) were significant centres of Christianity in the Roman Empire.[3] The raids and incursions into the Roman provinces in the 4th and the 5th centuries brought considerable damage to the ecclesiastical organisation of the Christian Church in the Bulgarian lands, yet did not destroy it.Boris I believed that cultural advancement and the sovereignty and prestige of a Christian Bulgaria could be achieved through an enlightened clergy governed by an autocephalous church.Following the Byzantine theory of "Imperium sine Patriarcha non staret", which said that a close relation should exist between an Empire and Patriarchate, Boris I greeted the arrival of the disciples of the recently deceased Saints Cyril and Methodius in 886 as an opportunity.Following Bulgaria's two decisive victories over the Byzantines at Acheloos (near the present-day city of Pomorie) and Katasyrtai (near Constantinople), the government declared the autonomous Bulgarian Archbishopric as autocephalous and elevated it to the rank of Patriarchate at an ecclesiastical and national council held in 919.On April 5, 972, Byzantine Emperor John I Tzimisces conquered and burned down Preslav, and captured Bulgarian Tsar Boris II.After Bulgaria fell under Byzantine domination in 1018, Emperor Basil II Bulgaroktonos (the “Bulgar-Slayer”) acknowledged the autocephalous status of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.To a large extent the archbishopric preserved its national character, upheld Slavonic liturgy, and continued its contribution to the development of Bulgarian literature.As a result of the successful uprising of the brothers Peter IV and Ivan Asen I in 1185/1186, the foundations of the Second Bulgarian Empire were laid with Tarnovo as its capital.Following Boris I’s principle that the sovereignty of the state is inextricably linked to the autocephaly of the Church, the two brothers immediately took steps to restore the Bulgarian Patriarchate.Under the reign of Tsar Ivan Asen II (1218–1241), conditions were created for the termination of the union with Rome and for the recognition of the autocephalous status of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church.Despite a reduction in size of the boundaries of the diocese of the Tarnovo Patriarchate at the end of the 13th century, its authority in the Eastern Orthodox world remained high.The millet system in the Ottoman Empire granted a number of important civil and judicial functions to the Patriarch of Constantinople and the diocesan metropolitans.Although the status and the guiding principles of the Exarchate reflected the canons, the Patriarchate argued that “surrender of Orthodoxy to ethnic nationalism” was essentially a manifestation of heresy.His successor, Joseph I, managed to develop and considerably extend its church and school network in the Bulgarian Principality, Eastern Rumelia, Macedonia and the Adrianople Vilayet.In 1913, Exarch Joseph I transferred his offices from Istanbul to Sofia; he died in 1915, a few months before Bulgaria fatefully opted to participate in World War I alongside the Central Powers.Bishop Boris was assassinated; Egumenius Kalistrat, administrator of the Rila Monastery, was imprisoned; and various other clergy were murdered or charged with crimes against the state.The 1970 commemoration served to recall that the exarchate (which retained its jurisdictional borders until after World War I) included Macedonia and Thrace in addition to present-day Bulgaria.The supreme clerical, judicial and administrative power for the whole domain of the Bulgarian Orthodox Church is exercised by the Holy Synod, which includes the Patriarch and the diocesan prelates, who are called metropolitans.

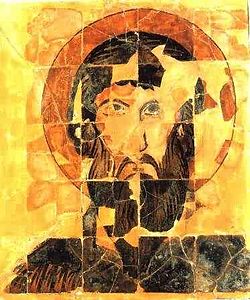

Eastern OrthodoxEastern ChristianityScriptureSeptuagintNew TestamentEastern Orthodox theologyDaniilBulgarianOld Church SlavonicAlexander Nevsky CathedralBulgariaUnited StatesCanadaAustraliaEuropean UnionArgentinaRussiaGreeceTurkeyBoris I of BulgariaAnthim IBulgarian ExarchateStefan I of BulgariaOld Calendar Bulgarian Orthodox ChurchBulgarian Orthodox Church – Alternative synodEastern Orthodox ChurchChrist PantocratorHagia SophiaStructureTheologyHistory of theologyLiturgyChurch historyView of salvationView of MaryCrucifixionResurrectionAscensionof JesusChristianityChristian ChurchApostolic successionFour Marks of the ChurchOrthodoxyOrganizationAutonomyAutocephalyPatriarchateEcumenical PatriarchCanon lawBishopsPriestsDegreesBratstvoAutocephalousConstantinopleAlexandriaAntiochJerusalemSerbiaRomaniaGeorgiaCyprusPolandAlbaniaCzech Lands and SlovakiaNorth MacedoniaAmericaUkraine (OCU)Ukraine (UOC)AutonomousFinlandEstonia (EP)Japan (MP)China (MP)Americas (RP)Bessarabia (RP)Moldova (MP)Crete (EP)Estonia (MP)ROCOR (MP)Australia, New Zealand, and OceaniaAustriaBelgium, Holland, and LuxembourgFranceGermanyGreat Britain and IrelandItaly and MaltaLatin AmericaScandinaviaSpain and PortugalSwitzerland and LiechtensteinUnited States of AmericaOld BelieversSpiritual ChristianityTrue OrthodoxyCatacomb ChurchOld CalendaristsAmerican Orthodox Catholic ChurchAmerican World PatriarchsAbkhaziaBelarusLatviaMontenegroUOC–KPEvangelical OrthodoxEcumenical councilsFirst Seven Ecumenical CouncilsSecondFourthSeventhEighthQuinisext CouncilMoscowConstantinople (1872)HistoryChurch FathersPentarchyByzantine EmpireChristianization of GeorgiaChristianization of BulgariaChristianization of Kievan Rus'Great SchismOttoman EmpireNorth America15th–16th c.History of Eastern Orthodox theology