Christianity in the ante-Nicene period

There was an explicit rejection of then-modern Judaism and Jewish culture by the end of the second century, with a growing body of adversus Judaeos literature.Fourth- and fifth-century Christianity experienced pressure from the government of the Roman Empire and developed strong episcopal and unifying structure.[3] Various local and provincial ancient church councils were held during this period, with the decisions meeting varying degrees of acceptance by different Christian groups.[4][5] The predominant eschatological view in the Ante-Nicene period was Premillennialism, the belief of a visible reign of Christ in glory on earth with the risen saints for a thousand years, before the general resurrection and judgment.[11] Other early premillennialists included Pseudo-Barnabas,[12] Papias,[13] Methodius, Lactantius,[14] Commodianus[15] Theophilus, Tertullian,[16] Melito,[17] Hippolytus of Rome and Victorinus of Pettau.If it was written by Hippolytus of Rome, Apostolic Tradition could be dated about 215, but recent scholars believe it to be material from separate sources ranging from the middle second to the fourth century,[30][31] being gathered and compiled about 375–400.[35] Instituted in the New Testament, in the early Church, "the verbal exchange of 'peace' with a kiss appears to be a Christian innovation, there being no clear example in pre-Christian literature."[46] The Holy Kiss was seen as an essential part of preparing to partaking in the Eucharist:[46] Peace, reconciliation, and unity were the very essence of the church's life; without them communion would have been a sham.[49] The early Church Father Clement of Alexandria linked the new sandals given by to Prodigal Son with feetwashing, describing "non-perishable shoes that are only fit to be worn by those who have had their feet washed by Jesus, the Teacher and Lord.Since the Nicene Creed came to define the Church, the early debates have long been regarded as a unified orthodox position against a minority of heretics.[54] While Bauer's original thesis has been criticised, Elaine Pagels and Bart Ehrman have further explicated the existence of variant Christianities in the first centuries.In addition to the broad spectrum of general branches of Christianity, there was constant change and diversity that variably resulted in both internecine conflicts and syncretic adoption.Some of the major movements were: In the middle of the second century, the Christian communities of Rome, for example, were divided between followers of Marcion, Montanism, and the gnostic teachings of Valentinus.Proto-orthodox Christianity, on the other hand, held that both the material and spiritual worlds were created by God and were therefore both good, and that this was represented in the unified divine and human natures of Christ.[65] (see Pastoral Epistles, c. 90–140[65]) Robert Williams posits that the "origin and earliest development of episcopacy and monepiscopacy and the ecclesiastical concept of (apostolic) succession were associated with crisis situations in the early church.One of these structures is the tri-partite form of church leadership consisting of episkopoi (overseers); presbyteroi (elders),[67] as was the case with Jewish communities; and diakonoi (ministerial servants).The Catholic Encyclopedia argues that although evidence is scarce in the second century, the primacy of the Church of Rome is asserted by Irenaeus of Lyons' document Against Heresies (AD 189).[68] In response to second century Gnostic teaching, Irenaeus created the first known document considered to be describing apostolic succession,[69] including the immediate successors of Peter and Paul: Linus, Anacleutus, Clement, Evaristus, Alexander, and Sixtus.[74] It had the prestige of being the city of Jesus's death and reported resurrection,[75] and was the center of the Apostolic Age, but it experienced decline during the years of the Jewish–Roman wars (66-135).The First Council of Nicaea recognized and confirmed the tradition by which Jerusalem continued to be given "special honour", but did not assign to it even metropolitan authority within its own province, still less the extraprovincial jurisdiction exercised by Rome and the other sees mentioned above.[78] William Kling states that by the end of second century that Rome was a significant, if not unique, early center of Christianity, but held no convincing claim to primacy.A bishop from Caesarea named Firmilian sided with Cyprian in his dispute, seething against Stephen's "insulting arrogance" and claims of authority based on the See of Peter.[80] By the end of the early Christian period, the church within the Roman Empire had hundreds of bishops, some of them (Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, "other provinces") holding some form of jurisdiction over others.Since the end of the 4th century, the title "Fathers of the Church" has been used to refer to a more or less clearly defined group of ecclesiastical writers who are appealed to as authorities on doctrinal matters.[92] His views of a hierarchical structure in the Trinity, the temporality of matter, "the fabulous preexistence of souls," and "the monstrous restoration which follows from it" were declared anathema in the 6th century.[102][106] Tertullian is said to have introduced the Latin term "trinitas" with regard to the Divine (Trinity) to the Christian vocabulary[107] (but Theophilus of Antioch already wrote of "the Trinity, of God, and His Word, and His wisdom", which is similar but not identical to the Trinitarian wording),[108] and also probably the formula "three Persons, one Substance" as the Latin "tres Personae, una Substantia" (itself from the Koine Greek "treis Hypostases, Homoousios"), and also the terms "vetus testamentum" (Old Testament) and "novum testamentum" (New Testament).[110] Elizabeth A. Clark says that the Church Fathers regarded women both as "God's good gift to men" and as "the curse of the world", both as "weak in both mind and character" and as people who "displayed dauntless courage, undertook prodigious feats of scholarship".[112] Although lasting only a year,[113] the Decian persecution was a severe departure from previous imperial policy that Christians were not to be sought out and prosecuted as inherently disloyal.[114] Even under Decius, orthodox Christians were subject to arrest only for their refusal to participate in Roman civic religion, and were not prohibited from assembling for worship.[120] Dag Øistein Endsjø argues that Christianity was helped by its promise of a general resurrection of the dead at the end of the world which was compatible with the traditional Greek belief that true immortality depended on the survival of the body.

Spread of Christianity to AD 325

Spread of Christianity to

AD 600

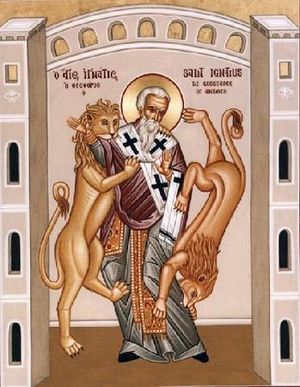

Christianity in the 4th centuryHistory of ChristianityChristianityChristNativityBaptismMinistryCrucifixionResurrectionAscensionOld TestamentNew TestamentGospelChurchNew CovenantTheologyTrinityFatherHoly SpiritApologeticsChristologyHistory of theologyMissionSalvationUniversalismHistoryTraditionApostlesEarly ChristianityChurch FathersConstantineCouncilsAugustineIgnatiusEast–West SchismCrusadesAquinasReformationLutherDenominations(full list)NiceneCatholicEasternOld CatholicPalmarian CatholicIndependent CatholicSedevacantismEastern OrthodoxOriental OrthodoxChurch of the EastProtestantAdventistAnabaptistAnglicanBaptistFree EvangelicalLutheranMethodistMoravian [Hussite]PentecostalPlymouth BrethrenQuakerReformedUnited ProtestantWaldensianNondenominational ChristianityRestorationistChristadelphiansIglesia ni CristoIrvingiansJehovah's WitnessesLatter Day SaintsMembers Church of God InternationalThe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day SaintsThe New Church (Swedenborgian)Unitarians and UniversalistsCivilizationCriticismCultureEcumenismGlossaryLiturgyOther religionsPrayerSermonSymbolismWorshipOutlineNational Roman MuseumVaticannecropolisDis ManibusIchthysChristian historyFirst Council of NicaeaApostolic Agefirst centuryproto-orthodoxyGreat ChurchApostolic FathersPauline ChristianityGnostic ChristianityJewish Christian churchancient church councilshereticsMarcionValentinusMontanusChristianActs of the ApostlesIgnatius of AntiochChristian eschatologyPremillennialismJustin MartyrIrenaeusAgainst HeresiesPseudo-BarnabasPapiasMethodiusLactantiusCommodianusTheophilusTertullianMelitoHippolytus of Rome