Religion in Switzerland

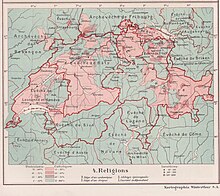

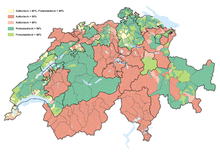

[4] Other religions present in the country include Hinduism and Buddhism, practised by both local Swiss who have nurtured interest in Eastern doctrines and by immigrants from Asia.[19] In the country there are also various new religious movements, among which one of the most influential has been the Theosophy-derived Anthroposophy; the Anthroposophical Society was established by the Austrian occultist Rudolf Steiner in the 1920s and 1930s in Dornach, Solothurn, and it is known for its promotion of the well-reputed Waldorf schools.[21] A Roman inscription with the Chi Rho symbol in Sion, dated 377, is the earliest datable record of Christianity in the territory of modern Switzerland.[18] At the beginning of the 13th century, the Old Swiss Confederacy began to emerge within the Holy Roman Empire from a pact between the cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden to resist the power of the House of Habsburg; the pact was soon joined by other territories and by the cities of Zürich, Bern and Basel, who wanted to remain independent from the Habsburgs and from the Dukes of Burgundy.[18] The Alemannic cantons of Zürich, Bern, Basel and Schaffhausen were the first to officially adopt the new religion under the influence of Huldrych Zwingli, while Geneva became the centre of the movement under the sway of John Calvin, who was French in origin.[24] During the Counter-Reformation enacted by the Catholic Church in the Council of Trent (1545–1563) to thwart the spread of Protestant movements, Geneva and other Protestant cantons became havens of refuge for Calvinists from elsewhere, and in the 17th century Switzerland welcomed French Huguenots who fled France after the Edict of Nantes (1598), through which Henry IV had granted them freedom in France, was revoked by Louis XIV with the Edict of Fontainebleau (1685).[6] To avoid the laceration of the system of alliances between territories, the confederacy adopted the principle of territorial exclusivity of religion (cuius regio, eius religio), thereby recognising the plurality of Christian denominations on a constitutional level, although in areas of mixed religious affiliation, including Aargau, Thurgau, the surroundings of St. Gallen, the Grisons and Geneva, armed conflicts between Catholics and Protestants continued.[26] After the end of the Helvetic Republic and the restoration of Switzerland as a confederation of states, conflicts between Catholics and Protestants arose again, although popular uprisings after 1830 led many cantons to adopt liberal constitutions which granted religious freedom.[26] In 1845, two Catholic cantons of central Switzerland, namely Fribourg and Valais, formed a separate league, the Sonderbund, which opposed Protestants and liberals.[29] Over the following decades, freedom of worship and secular principles, combined with free movement of the population, gradually loosened the system of territorial exclusivity of religions which was characteristic of old Switzerland.[34] After the World War II, the religious composition of the country began to change significantly; the immigration of workers from Italy and Spain sustained a growth of the Catholic population until 1970.[18] Starting in the mid-1970s, new waves of migration brought to Switzerland Orthodox Christian and Islamic populations from the Balkans, which increased in the 1990s with the welcoming of refugees fleeing the Yugoslav Wars.

UnaffiliatedCatholicismSwiss ProtestantismOther ChristianJudaismSt. PeterFraumünsterZürichSwitzerlandChristianitySwiss Federal Statistical Officeresident populationCatholicsSwiss ProtestantsChristian denominationsOrthodoxProtestantsProtestant Church of SwitzerlandGaulishHelvetiiGermanicAlemannilate Roman dominationFrankish dominationGallo-RomanGermanic paganismsOld Swiss Confederacyone of the centresProtestant ReformationCalvinismSonderbund Warstate religioncantonsGenevaNeuchâtelLandeskirchenOld Catholic ChurchJewish congregationstaxation of their adherentsJewish Museum of Switzerlandmunicipalityabsolute majorityAargauSt. GallenLuzernTicinoValaisFribourgBasel-LandschaftThurgauSolothurnGrisonsBasel-StadtSchwyzSchaffhausenAppenzell AusserrhodenInnerrhodenNidwaldenGlarusObwaldenSwiss nationalsItalianPortugueseGermanFrenchmenBalkansAlbaniaSerbiaBosnia and HerzegovinaMontenegroNorth MacedoniaKosovoCatholic Church in SwitzerlandSerbian Orthodox Eparchy of Austria and SwitzerlandThe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in SwitzerlandLutheransEvangelicalsJehovah's WitnessesEinsiedeln AbbeyBenedictinesEinsiedelncanton of SchwyzChurch of Saint PaulRussian OrthodoxArmenian ApostolicBern Switzerland Templethe Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day SaintsSeventh-day AdventistIslam in SwitzerlandHinduism in SwitzerlandBuddhism in SwitzerlandSikhism in SwitzerlandHistory of the Jews in SwitzerlandBalkanTurkishIranianHinduismBuddhismTaoistBulletfeng shuiTaoist traditionInfinityMin MountainsSichuannew religious movementsTheosophyAnthroposophyAnthroposophical SocietyoccultistRudolf SteinerDornachWaldorf schoolscanton of St. GallenTrimbachcanton of SolothurnTheravadaGretzenbachLa Chaux-de-Fondscanton of NeuchâtelMasonicLindenhof hillGoetheanumMuri statuette groupMuri bei BernJupiter