Periodic table

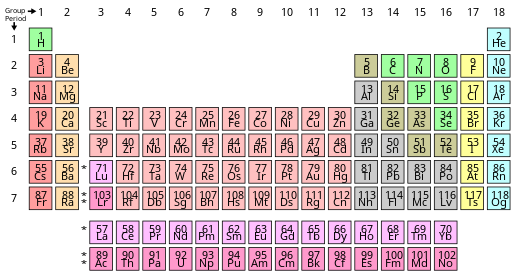

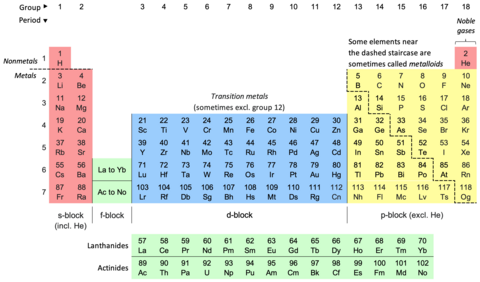

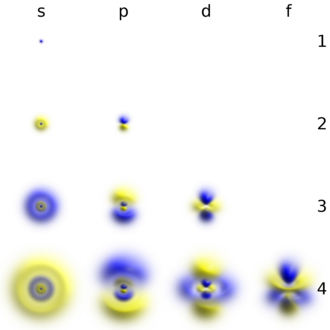

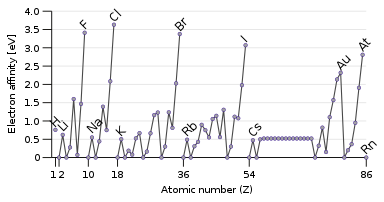

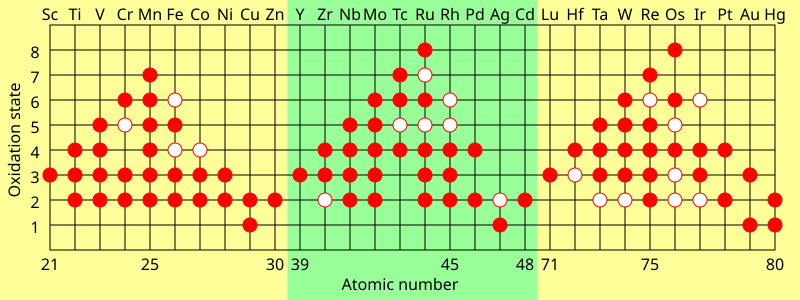

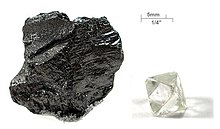

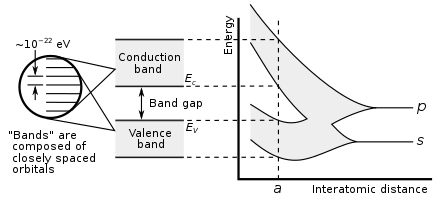

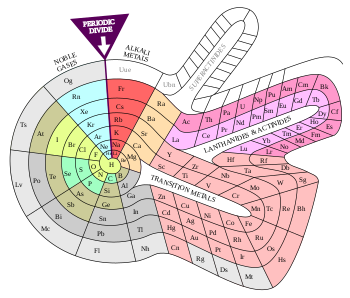

The single exception is helium, which has two valence electrons like beryllium and magnesium, but is typically placed in the column of neon and argon to emphasise that its outer shell is full.[61] As there are now not only 4f but also 5d and 6s subshells at similar energies, competition occurs once again with many irregular configurations;[50] this resulted in some dispute about where exactly the f-block is supposed to begin, but most who study the matter agree that it starts at lanthanum in accordance with the Aufbau principle.[87][88][57] This last option has nonetheless been criticized by the chemist and philosopher of science Eric Scerri on the grounds that it appears to imply that hydrogen is above the periodic law altogether, unlike all the other elements.This relates to the electronic argument, as the reason for neon's greater inertness is repulsion from its filled p-shell that helium lacks, though realistically it is unlikely that helium-containing molecules will be stable outside extreme low-temperature conditions (around 10 K).[25] A third form can sometimes be encountered in which the spaces below yttrium in group 3 are left empty, such as the table appearing on the IUPAC web site,[6] but this creates an inconsistency with quantum mechanics by making the f-block 15 elements wide (La–Lu and Ac–Lr) even though only 14 electrons can fit in an f-subshell.[24][33][101][102][103] While the 2021 IUPAC report noted that 15-element-wide f-blocks are supported by some practitioners of a specialized branch of relativistic quantum mechanics focusing on the properties of superheavy elements, the project's opinion was that such interest-dependent concerns should not have any bearing on how the periodic table is presented to "the general chemical and scientific community".Thus higher s-, p-, d-, and f-subshells experience strong repulsion from their inner analogues, which have approximately the same angular distribution of charge, and must expand to avoid this.[118] The 4p and 5d atoms, coming immediately after new types of transition series are first introduced, are smaller than would have been expected,[122] because the added core 3d and 4f subshells provide only incomplete shielding of the nuclear charge for the outer electrons.The shielding effect of adding an extra 3d electron approximately compensates the rise in nuclear charge, and therefore the ionisation energies stay mostly constant, though there is a small increase especially at the end of each transition series.[135] (They can form metastable resonances if the incoming electron arrives with enough kinetic energy, but these inevitably and rapidly autodetach: for example, the lifetime of the most long-lived He− level is about 359 microseconds.[112] However, towards the right side of the d- and f-blocks, the theoretical maximum corresponding to using all valence electrons is not achievable at all;[137] the same situation affects oxygen, fluorine, and the light noble gases up to krypton.[140] The lanthanides and late actinides generally show a stable +3 oxidation state, removing the outer s-electrons and then (usually) one electron from the (n−2)f-orbitals, that are similar in energy to ns.The stable elements of group 14 comprise a nonmetal (carbon), two semiconductors (silicon and germanium), and two metals (tin and lead); they are nonetheless united by having four valence electrons.In a metal, the bonding and antibonding orbitals have overlapping energies, creating a single band that electrons can freely flow through, allowing for electrical conduction.Those forming discrete molecules are held together mostly by dispersion forces, which are more easily overcome; thus they tend to have lower melting and boiling points,[173] and many are liquids or gases at room temperature.[52] IUPAC recommends the names lanthanoids and actinoids to avoid ambiguity, as the -ide suffix typically denotes a negative ion; however lanthanides and actinides remain common.Mendeleev predicted the properties of three of these unknown elements in detail: as they would be missing heavier homologues of boron, aluminium, and silicon, he named them eka-boron, eka-aluminium, and eka-silicon ("eka" being Sanskrit for "one").[209][210]: 45 In 1875, the French chemist Paul-Émile Lecoq de Boisbaudran, working without knowledge of Mendeleev's prediction, discovered a new element in a sample of the mineral sphalerite, and named it gallium.[212] In 1889, Mendeleev noted at the Faraday Lecture to the Royal Institution in London that he had not expected to live long enough "to mention their discovery to the Chemical Society of Great Britain as a confirmation of the exactitude and generality of the periodic law".[33] After the internal structure of the atom was probed, amateur Dutch physicist Antonius van den Broek proposed in 1913 that the nuclear charge determined the placement of elements in the periodic table.[215] Although Moseley was soon killed in World War I, the Swedish physicist Manne Siegbahn continued his work up to uranium, and established that it was the element with the highest atomic number then known (92).The contemporarily accepted discovery of element 75 came in 1925, when Walter Noddack, Ida Tacke, and Otto Berg independently rediscovered it and gave it its present name, rhenium.[33] The exact position of the lanthanides, and thus the composition of group 3, remained under dispute for decades longer because their electron configurations were initially measured incorrectly.In particular, ytterbium completes the 4f shell and thus Soviet physicists Lev Landau and Evgeny Lifshitz noted in 1948 that lutetium is correctly regarded as a d-block rather than an f-block element;[26] that bulk lanthanum is an f-metal was first suggested by Jun Kondō in 1963, on the grounds of its low-temperature superconductivity.[100] This clarified the importance of looking at low-lying excited states of atoms that can play a role in chemical environments when classifying elements by block and positioning them on the table.[63][65][25] Many authors subsequently rediscovered this correction based on physical, chemical, and electronic concerns and applied it to all the relevant elements, thus making group 3 contain scandium, yttrium, lutetium, and lawrencium[63][23][92] and having lanthanum through ytterbium and actinium through nobelium as the f-block rows:[63][23] this corrected version achieves consistency with the Madelung rule and vindicates Bassett, Werner, and Bury's initial chemical placement.As such, IUPAC and the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP) created a Transfermium Working Group (TWG, fermium being element 100) in 1985 to set out criteria for discovery,[247] which were published in 1991.The LBNL in the United States, the JINR in Russia, and the Heavy Ion Research Facility in Lanzhou (HIRFL) in China also plan to make their own attempts at synthesizing the first few period 8 elements.[59][264][265][266][267] Elements 121 through 156 thus do not fit well as chemical analogues of any previous group in the earlier parts of the table,[128] although they have sometimes been placed as 5g, 6f, and other series to formally reflect their electron configurations.[289][288] Janet's left-step table is being increasingly discussed as a candidate for being the optimal or most fundamental form; Scerri has written in support of it, as it clarifies helium's nature as an s-block element, increases regularity by having all period lengths repeated, faithfully follows Madelung's rule by making each period correspond to one value of n + ℓ,[g] and regularises atomic number triads and the first-row anomaly trend.

(In grey tin, the band gap vanishes and metallization occurs. [ 148 ] Tin has another allotrope, white tin, whose structure is even more metallic.)

Periodic table (disambiguation)sets of elementsdividing line between metals and nonmetalsgroups 2AlternativeextendedPeriodic table historyD. Mendeleev1869 predictionsDiscovery of elementsNamingetymologyfor peoplefor placescontroversiesin East AsiaSystematic element namesGroupsalkali metals2 (alkaline earth metals)15 (pnictogens)16 (chalcogens)17 (halogens)18 (noble gases)PeriodsBlocksAtomic orbitalsAufbau principlemetallic classificationMetalsalkalialkaline earthtransitionpost-transitionlanthanideactinideMetalloidsdividing metals and nonmetalsNonmetalsnonmetal halogennoble gasCoinage metalsPlatinum-group metalsPrecious metalsRefractory metalsHeavy metalsLight metalsNative metalsNoble metalsMain-group elementsRare-earth elementsTransuraniumtrans-ElementsList of chemical elementsby abundancein human bodyby atomic propertiesby isotope stabilityby symbolRelative atomic massCrystal structureaffinityconfigurationElectronegativityGoldschmidt classificationNutritionValenceAbundanceAtomic radiusBoiling pointCritical pointDensityElasticityElectrical resistivityHardnesscapacityof fusionof vaporizationIonization energyMelting pointOxidation stateSpeed of soundconductivityexpansion coefficientVapor pressurechemical elementschemistryphysicsperiodic lawatomic numbersrecurrence of their propertiestrendsMetallicNonmetallicDmitri Mendeleevatomic masspredict some properties of some of the missing elementsquantum mechanicsGlenn T. Seaborgactinidessynthesizebeyond these seven rowsalternative representationsPeriodHydrogen1H1.0080Helium2He4.0026Lithium3Li6.94Beryllium4Be9.0122Boron5B10.81Carbon6C12.011Nitrogen7N14.007Oxygen8O15.999Fluorine9F18.998Neon10Ne20.180Sodium11Na22.990Magnesium12Mg24.305Aluminium13Al26.982Silicon14Si28.085Phosphorus15P30.974Sulfur16S32.06Chlorine17Cl35.45Argon18Ar39.95Potassium19K39.098Calcium20Ca40.078Scandium21Sc44.956