Inorganic chemistry

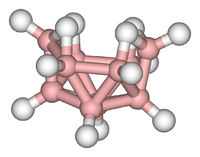

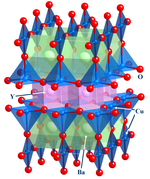

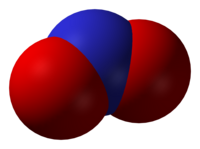

It has applications in every aspect of the chemical industry, including catalysis, materials science, pigments, surfactants, coatings, medications, fuels, and agriculture.[3][4] Inorganic compounds are also found multitasking as biomolecules: as electrolytes (sodium chloride), in energy storage (ATP) or in construction (the polyphosphate backbone in DNA).The stereochemistry of coordination complexes can be quite rich, as hinted at by Werner's separation of two enantiomers of [Co((OH)2Co(NH3)4)3]6+, an early demonstration that chirality is not inherent to organic compounds.These species feature elements from groups I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, 0 (excluding hydrogen) of the periodic table.Experiments on oxygen, O2, by Lavoisier and Priestley not only identified an important diatomic gas, but opened the way for describing compounds and reactions according to stoichiometric ratios.Conversely, organic compounds lacking (many) hydrogen ligands can be classed as "inorganic", such as the fullerenes, buckytubes and binary carbon oxides.This interface is the chemical basis of nanoscience or nanotechnology and specifically arise from the study of quantum size effects in cadmium selenide clusters.By definition, these compounds occur in nature, but the subfield includes anthropogenic species, such as pollutants (e.g., methylmercury) and drugs (e.g., Cisplatin).[12] The field, which incorporates many aspects of biochemistry, includes many kinds of compounds, e.g., the phosphates in DNA, and also metal complexes containing ligands that range from biological macromolecules, commonly peptides, to ill-defined species such as humic acid, and to water (e.g., coordinated to gadolinium complexes employed for MRI).Medicinal inorganic chemistry includes the study of both non-essential and essential elements with applications to diagnosis and therapies.Spectroscopic features are analyzed and described with respect to the symmetry properties of the, inter alia, vibrational or electronic states.Knowledge of the symmetry properties of the ground and excited states allows one to predict the numbers and intensities of absorptions in vibrational and electronic spectra.A classic concept in inorganic thermodynamics is the Born–Haber cycle, which is used for assessing the energies of elementary processes such as electron affinity, some of which cannot be observed directly.Elements heavier than C, N, O, and F often form compounds with more electrons than predicted by the octet rule, as explained in the article on hypervalent molecules.Elements lighter than carbon (B, Be, Li) as well as Al and Mg often form electron-deficient structures that are electronically akin to carbocations.The large and industrially important area of catalysis hinges on the ability of metals to modify the reactivity of organic ligands.Older methods tended to examine bulk properties such as the electrical conductivity of solutions, melting points, solubility, and acidity.Commonly encountered techniques are: Although some inorganic species can be obtained in pure form from nature, most are synthesized in chemical plants and in the laboratory.Volatile compounds and gases are manipulated in "vacuum manifolds" consisting of glass piping interconnected through valves, the entirety of which can be evacuated to 0.001 mm Hg or less.

Inorganic Chemistry (journal)potassium oxidesynthesisinorganicorganometallicchemical compoundsorganic chemistryorganometallic chemistrycatalysismaterials sciencepigmentssurfactantscoatingsmedicationsagriculturemineralsiron sulfidepyritegypsumbiomoleculessodium chloridepolyphosphateInorganic compoundsionic compoundscationsanionsionic bondingmagnesium chloridemagnesiumchloridesodium hydroxidesodiumhydroxidesulfur dioxideiron pentacarbonylpolar covalentoxidescarbonateshalidesmelting pointshydrogen atomsacid-base chemistryLewis acidLewis baseHSAB theorypolarizabilityorganic synthesiscluster chemistrymetal–metal bondsbridging ligandsbioinorganic chemistrymedicinal chemistrymaterials chemistrysolid state chemistryceramicssulfuric acidammonium nitrateHaber processportland cementcatalystsvanadium(V) oxidetitanium(III) chloridepolymerization of alkenesreagentslithium aluminium hydridechelatesCoordination chemistrylone pairslanthanidesactinidesenantiomers[Co((OH)2Co(NH3)4)3]6+[Co(NH3)6]3+titanium tetrachloridecisplatinTetrasulfur tetranitridegroupssulfurphosphorusLavoisierPriestleydiatomicstoichiometricammoniaCarl BoschFritz HaberphosphatebuckytubesdiboranesiliconesbuckminsterfullereneNoble gas compoundskryptonxenon hexafluoridexenon trioxidekrypton difluorideOrganolithium reagentsn-butyllithiumlipophilicmetal carbonylsalkoxidesCyclopentadienyliron dicarbonyl dimerferrocenemolybdenum hexacarbonyltriethylboraneTris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium(0)Decaboranecluster compoundIron–sulfur clustersiron–sulfur proteinsmetabolismnanotechnologyquantum size effectscadmium selenideFe3(CO)12B10H14[Mo6Cl14]2−4Fe-4ScobaltVitamin B12Bioorganometallic chemistrymethylmercurypeptideshumic acidgadoliniumessential elements