Alchemy

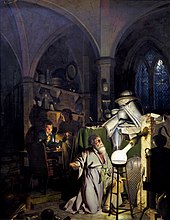

Alchemy (from the Arabic word al-kīmīā, الكیمیاء) is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practised in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe.[7] Modern discussions of alchemy are generally split into an examination of its exoteric practical applications and its esoteric spiritual aspects, despite criticisms by scholars such as Eric J. Holmyard and Marie-Louise von Franz that they should be understood as complementary.[8][9] The former is pursued by historians of the physical sciences, who examine the subject in terms of early chemistry, medicine, and charlatanism, and the philosophical and religious contexts in which these events occurred.[15] Others trace its roots to the Egyptian name kēme (hieroglyphic 𓆎𓅓𓏏𓊖 kmt ), meaning 'black earth', which refers to the fertile and auriferous soil of the Nile valley, as opposed to red desert sand.The start of Western alchemy may generally be traced to ancient and Hellenistic Egypt, where the city of Alexandria was a center of alchemical knowledge, and retained its pre-eminence through most of the Greek and Roman periods.[16] Following the work of André-Jean Festugière, modern scholars see alchemical practice in the Roman Empire as originating from the Egyptian goldsmith's art, Greek philosophy and different religious traditions.[34] An important example of alchemy's roots in Greek philosophy, originated by Empedocles and developed by Aristotle, was that all things in the universe were formed from only four elements: earth, air, water, and fire.In the late ninth and early tenth centuries, the Arabic works attributed to Jābir ibn Hayyān (Latinized as "Geber" or "Geberus") introduced a new approach to alchemy.The efforts of Berthelot and Ruelle to put a little order in this mass of literature led only to poor results, and the later researchers, among them in particular Mrs. Hammer-Jensen, Tannery, Lagercrantz, von Lippmann, Reitzenstein, Ruska, Bidez, Festugière and others, could make clear only few points of detail ....An even surface examination of the Greek texts shows that a very small part only was organized according to true experiments of laboratory: even the supposedly technical writings, in the state where we find them today, are unintelligible nonsense which refuses any interpretation.The relatively clear description of the processes and the alchemical apparati, the methodical classification of the substances, mark an experimental spirit which is extremely far away from the weird and odd esotericism of the Greek texts.Jabir developed an elaborate numerology whereby the root letters of a substance's name in Arabic, when treated with various transformations, held correspondences to the element's physical properties.[57] From the 9th to 14th centuries, alchemical theories faced criticism from a variety of practical Muslim chemists, including Alkindus,[58] Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī,[59] Avicenna[60] and Ibn Khaldun.Discovered in BC China, the "magic square of three" was propagated to followers of Abū Mūsā Jābir ibn Ḥayyān at some point over the proceeding several hundred years.[66] In his work Inner Chapters of the Book of the Master Who Embraces Spontaneous Nature (317 AD), Hong argued that alchemical solutions such as elixirs were preferable to traditional medicinal treatment due to the spiritual protection they could provide.[64] In the early Song dynasty, followers of this Taoist idea (chiefly the elite and upper class) would ingest mercuric sulfide, which, though tolerable in low levels, led many to suicide.The translation of Arabic texts concerning numerous disciplines including alchemy flourished in 12th-century Toledo, Spain, through contributors like Gerard of Cremona and Adelard of Bath.[77] Albertus Magnus, a Dominican friar, is known to have written works such as the Book of Minerals where he observed and commented on the operations and theories of alchemical authorities like Hermes Trismegistus, pseudo-Democritus and unnamed alchemists of his time.They believed in the four elements and the four qualities as described above, and they had a strong tradition of cloaking their written ideas in a labyrinth of coded jargon set with traps to mislead the uninitiated.The 14th century saw the Christian imagery of death and resurrection employed in the alchemical texts of Petrus Bonus, John of Rupescissa, and in works written in the name of Raymond Lull and Arnold of Villanova.[88][89] A common idea in European alchemy in the medieval era was a metaphysical "Homeric chain of wise men that link[ed] heaven and earth"[90] that included ancient pagan philosophers and other important historical figures.Although better known for angel summoning, divination, and his role as astrologer, cryptographer, and consultant to Queen Elizabeth I, Dee's alchemical[97] Monas Hieroglyphica, written in 1564 was his most popular and influential work.[100] Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, in the late 16th century, famously received and sponsored various alchemists at his court in Prague, including Dee and his associate Edward Kelley.Michael Sendivogius (Michał Sędziwój, 1566–1636), a Polish alchemist, philosopher, medical doctor and pioneer of chemistry wrote mystical works but is also credited with distilling oxygen in a lab sometime around 1600.Early modern European alchemy continued to exhibit a diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: "Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian, Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and more—plus virtually every combination and compromise thereof.[109][110] The esoteric or occultist school that arose during the 19th century held the view that the substances and operations mentioned in alchemical literature are to be interpreted in a spiritual sense, less than as a practical tradition or protoscience.[126] As the language of the alchemists is analysed, historians are becoming more aware of the connections between that discipline and other facets of Western cultural history, such as the evolution of science and philosophy, the sociology and psychology of the intellectual communities, kabbalism, spiritualism, Rosicrucianism, and other mystic movements.[130] At the opposite end of the spectrum, focusing on the esoteric, scholars, such as Florin George Călian[131] and Anna Marie Roos,[132] who question the reading of Principe and Newman, interpret these same Decknamen as spiritual, religious, or psychological concepts.[134] According to this view, early alchemists such as Zosimos of Panopolis (c. 300 AD) highlighted the spiritual nature of the alchemical quest, symbolic of a religious regeneration of the human soul.The volumes of work he wrote shed new light onto understanding the art of transubstantiation and renewed alchemy's popularity as a symbolic process of coming into wholeness as a human being where opposites are brought into contact and inner and outer, spirit and matter are reunited in the hieros gamos, or divine marriage.

Alchemist (disambiguation)Alchemy (disambiguation)OuroborosAurora consurgensZentralbibliothek ZürichWestern esotericismEastern esotericismAstrologyGnosisHermeticismKabbalahMetaphysicsMystical theologyMysticismOccultThelemaTheosophyTraditionalismAstral projectionBody of lightDivinationEsoteric transmissionEvocationExorcismInitiationInvocationMeditationPropitiationRite of passageRitual purificationSacrificeA∴A∴Élus CoënsFreemasonryGolden DawnMartinismRosicrucianismTariqaTyphonian OrderList of magical organizationsBrotherhood of MyriamBlavatskyBöhmeBurckhardtCrowleyDionysiusFaivreGuénonGurdjieffHermes TrismegistusIbn ArabiMathersOldmeadowParacelsusPythagorasSchuonSteinerGiuliano KremmerzAnthroposophyEsoteric HitlerismGnosticismArabicnatural philosophyphilosophicalprotoscientificMuslim worldEuropepseudepigraphicalGreco-Roman Egyptchrysopoeiabase metalsnoble metalselixir of immortalitypanaceasmagnum opusphilosophers' stonelaboratory techniquesAncient Greek philosophicalfour elementscyphers12th-century translationsmedieval Islamic works on sciencerediscovery of Aristotelian philosophyearly modernchemistrymedicineesotericEric J. HolmyardMarie-Louise von Franzhistorians of the physical sciencesearly chemistrycharlatanismreligiousesotericismpsychologistsspiritualistsEtymology of chemistryold FrenchMedieval LatinLate GreektransmutationEgyptianWallis BudgeCopticBohairicDemoticChinese alchemyIndian alchemyIndian subcontinentMediterraneanIslamic worldmedieval EuropeTaoismDharmic faithsWestern religionsHermetic writingsLiber Hermetis (astrological)Definitions of Hermes TrismegistusCorpus HermeticumPoimandresAsclepiusDiscourse on the Eighth and NinthPrayer of ThanksgivingKorē kosmouCyranidesThe Book of the Secrets of the Stars