Special relativity

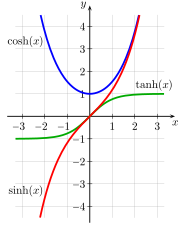

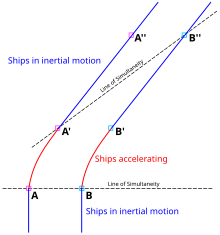

[p 1] Maxwell's equations of electromagnetism appeared to be incompatible with Newtonian mechanics, and the Michelson–Morley experiment failed to detect the Earth's motion against the hypothesized luminiferous aether.Special relativity corrects the hitherto laws of mechanics to handle situations involving all motions and especially those at a speed close to that of light (known as relativistic velocities).[3][4] Even so, the Newtonian model is still valid as a simple and accurate approximation at low velocities (relative to the speed of light), for example, everyday motions on Earth.As long as the universe can be modeled as a pseudo-Riemannian manifold, a Lorentz-invariant frame that abides by special relativity can be defined for a sufficiently small neighborhood of each point in this curved spacetime.In his initial presentation of special relativity in 1905 he expressed these postulates as:[p 1] The constancy of the speed of light was motivated by Maxwell's theory of electromagnetism[13] and the lack of evidence for the luminiferous ether.The derivation of special relativity depends not only on these two explicit postulates, but also on several tacit assumptions (made in almost all theories of physics), including the isotropy and homogeneity of space and the independence of measuring rods and clocks from their past history.The term reference frame as used here is an observational perspective in space that is not undergoing any change in motion (acceleration), from which a position can be measured along 3 spatial axes (so, at rest or constant velocity).An event is an occurrence that can be assigned a single unique moment and location in space relative to a reference frame: it is a "point" in spacetime.Although it is not as easy to perform exact computations using them as directly invoking the Lorentz transformations, their main power is their ability to provide an intuitive grasp of the results of a relativistic scenario.are related to the unprimed coordinates through the Lorentz transformations and could be approximately measured from the graph (assuming that it has been plotted accurately enough), but the real merit of a Minkowski diagram is its granting us a geometric view of the scenario., there are three cases to note:[21][27]: 25–39 The interweaving of space and time revokes the implicitly assumed concepts of absolute simultaneity and synchronization across non-comoving frames.Among his numerous contributions to the foundations of special relativity were independent work on the mass–energy relationship, a thorough examination of the twin paradox, and investigations into rotating coordinate systems.His name is frequently attached to a hypothetical construct called a "light-clock" (originally developed by Lewis and Tolman in 1909[32]), which he used to perform a novel derivation of the Lorentz transformation.The concept of time dilation is frequently taught using a light-clock that is traveling in uniform inertial motion perpendicular to a line connecting the two mirrors.Although observer A is traveling rapidly along a train, from her point of view the emission and receipt of the pulse occur at the same place, and she measures the interval using a single clock located at the precise position of these two events.[39] The reciprocity of time dilation between two observers in separate inertial frames leads to the so-called twin paradox, articulated in its present form by Langevin in 1911.This result appears puzzling because both the traveler and an Earthbound observer would see the other as moving, and so, because of the reciprocity of time dilation, one might initially expect that each should have found the other to have aged less.These time intervals (which can be, and are, actually measured experimentally by relevant observers) are different in another coordinate system moving with respect to the first, unless the events, in addition to being co-local, are also simultaneous.Interpreted in such a fashion, they are commonly referred to as the relativistic velocity addition (or composition) formulas, valid for the three axes of S and S′ being aligned with each other (although not necessarily in standard configuration).The classical calculation of the displacement takes two forms and makes different predictions depending on whether the receiver, the source, or both are in motion with respect to the medium.Nevertheless, relativistic Doppler shift for the longitudinal case, with source and receiver moving directly towards or away from each other, can be derived as if it were the classical phenomenon, but modified by the addition of a time dilation term, and that is the treatment described here.Although, as discussed above, subsequent scholarship has established that his arguments fell short of a broadly definitive proof, the conclusions that he reached in this paper have stood the test of time.Besides the vigorous debate that continues until this day as to the formal correctness of his original derivation, the recognition of special relativity as being what Einstein called a "principle theory" has led to a shift away from reliance on electromagnetic phenomena to purely dynamic methods of proof.The γ factor can be written as Transformations describing relative motion with uniform velocity and without rotation of the space coordinate axes are called boosts.For instance, demonstrating relativistic invariance of Maxwell's equations in their usual form is not trivial, while it is merely a routine calculation, really no more than an observation, using the field strength tensor formulation.Equations generalizing the electromagnetic effects found that finite propagation speed of the E and B fields required certain behaviors on charged particles.But at macroscopic scales and in the absence of strong gravitational fields, special relativity is experimentally tested to extremely high degree of accuracy (10−20)[84] and thus accepted by the physics community.Basically, special relativity can be stated as the invariance of any spacetime interval (that is the 4D distance between any two events) when viewed from any inertial reference frame.The notation makes it clear the equations are manifestly covariant under the Poincaré group, thus bypassing the tedious calculations to check this fact.Given the four-dimensional nature of spacetime the Minkowski metric η has components (valid with suitably chosen coordinates), which can be arranged in a 4 × 4 matrix:

Albert EinsteinAnnus Mirabilis papersPrinciple of relativityTheory of relativityFormulationsEinstein's postulatesInertial frame of referenceSpeed of lightMaxwell's equationsLorentz transformationTime dilationLength contractionRelativistic massMass–energy equivalenceRelativity of simultaneityRelativistic Doppler effectThomas precessionRelativistic diskBell's spaceship paradoxEhrenfest paradoxSpacetimeMinkowski spacetimeSpacetime diagramWorld lineLight coneDynamicsProper timeProper massFour-momentumHistoryGalilean relativityGalilean transformationAether theoriesEinsteinSommerfeldMichelsonMorleyFitzGeraldHerglotzLorentzPoincaréMinkowskiFizeauAbrahamPlanckvon LaueEhrenfestTolmanphysicsspace and timetwo postulateslaws of physicsinvariantinertial frames of referenceframes of referenceaccelerationvacuumGalileo GalileiGalilean invarianceHistory of special relativityelectromagnetismNewtonian mechanicsMichelson–Morley experimentluminiferous aetherLorentz transformationsHendrik LorentzDoppler effectspatialspacetime intervalenergyGalilean transformationsa single continuum known as "spacetime"general relativityHenri PoincaréHermann Minkowskispecial casecurvature of spacetimeenergy–momentum tensorgravityaccelerationsaccelerating frames of referencegravitational fieldstidal forcesfree fallnon-Euclidean geometryMinkowski spacepseudo-Riemannian manifoldcurved spacetimeprivileged reference framesGalileo's principle of relativityelectrodynamicsPostulates of special relativityMaxwell's theory of electromagnetismluminiferous ethermade in almost all theories of physicsisotropyhomogeneityPoincaré groupReference framesGalilean reference framesinertial reference frameGalileoelectromagnetic wavesaetherabsolute reference frameDerivations of the Lorentz transformationsMinkowski diagramLorentz factorone-parameter grouplinear mappingsrapidityLorentz scalarMinkowski diagramsCartesian planeTwin paradoxRelativistic mechanicscounterintuitivePoincaré transformationisometryLorentz booststranslationsreflectionsrotationsLadder paradoxabsolute simultaneitySagnac effect