Conservation of energy

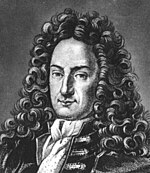

However, this is believed to be possible only under the most extreme of physical conditions, such as likely existed in the universe very shortly after the Big Bang or when black holes emit Hawking radiation.[3] In quantum mechanics, Noether's theorem is known to apply to the expected value, making any consistent conservation violation provably impossible, but whether individual conservation-violating events could ever exist or be observed is subject to some debate.Empedocles (490–430 BCE) wrote that in his universal system, composed of four roots (earth, air, water, fire), "nothing comes to be or perishes";[5] instead, these elements suffer continual rearrangement.Epicurus (c. 350 BCE) on the other hand believed everything in the universe to be composed of indivisible units of matter—the ancient precursor to 'atoms'—and he too had some idea of the necessity of conservation, stating that "the sum total of things was always such as it is now, and such it will ever remain."[6] In 1605, the Flemish scientist Simon Stevin was able to solve a number of problems in statics based on the principle that perpetual motion was impossible.[7] In his Horologium Oscillatorium, Huygens gave a much clearer statement regarding the height of ascent of a moving body, and connected this idea with the impossibility of perpetual motion.However, the researchers were quick to recognize that the principles set out in the book, while fine for point masses, were not sufficient to tackle the motions of rigid and fluid bodies.Inspired by the theories of Gottfried Leibniz, she repeated and publicized an experiment originally devised by Willem 's Gravesande in 1722 in which balls were dropped from different heights into a sheet of soft clay.The deformation of the clay was found to be directly proportional to the height from which the balls were dropped, equal to the initial potential energy.[10][11] Engineers such as John Smeaton, Peter Ewart, Carl Holtzmann [de; ar], Gustave-Adolphe Hirn, and Marc Seguin recognized that conservation of momentum alone was not adequate for practical calculation and made use of Leibniz's principle.The recalibration of vis viva to which can be understood as converting kinetic energy to work, was largely the result of Gaspard-Gustave Coriolis and Jean-Victor Poncelet over the period 1819–1839.In the paper Über die Natur der Wärme (German "On the Nature of Heat/Warmth"), published in the Zeitschrift für Physik in 1837, Karl Friedrich Mohr gave one of the earliest general statements of the doctrine of the conservation of energy: "besides the 54 known chemical elements there is in the physical world one agent only, and this is called Kraft [energy or work].In the middle of the eighteenth century, Mikhail Lomonosov, a Russian scientist, postulated his corpusculo-kinetic theory of heat, which rejected the idea of a caloric.The mechanical equivalence principle was first stated in its modern form by the German surgeon Julius Robert von Mayer in 1842.[14] Mayer reached his conclusion on a voyage to the Dutch East Indies, where he found that his patients' blood was a deeper red because they were consuming less oxygen, and therefore less energy, to maintain their body temperature in the hotter climate.He discovered that heat and mechanical work were both forms of energy, and in 1845, after improving his knowledge of physics, he published a monograph that stated a quantitative relationship between them.In one of them, now called the "Joule apparatus", a descending weight attached to a string caused a paddle immersed in water to rotate.In 1844, the Welsh scientist William Robert Grove postulated a relationship between mechanics, heat, light, electricity, and magnetism by treating them all as manifestations of a single "force" (energy in modern terms).[16] In 1847, drawing on the earlier work of Joule, Sadi Carnot, and Émile Clapeyron, Hermann von Helmholtz arrived at conclusions similar to Grove's and published his theories in his book Über die Erhaltung der Kraft (On the Conservation of Force, 1847).[18] In 1877, Peter Guthrie Tait claimed that the principle originated with Sir Isaac Newton, based on a creative reading of propositions 40 and 41 of the Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica.The produced electromagnetic radiant energy contributes just as much to the inertia (and to any weight) of the system as did the rest mass of the electron and positron before their demise.[20][21] This problem was eventually resolved in 1933 by Enrico Fermi who proposed the correct description of beta-decay as the emission of both an electron and an antineutrino, which carries away the apparently missing energy.Each of the four components (one of energy and three of momentum) of this vector is separately conserved across time, in any closed system, as seen from any given inertial reference frame.Thus, the rule of conservation of energy over time in special relativity continues to hold, so long as the reference frame of the observer is unchanged.If the metric under consideration is static (that is, does not change with time) or asymptotically flat (that is, at an infinite distance away spacetime looks empty), then energy conservation holds without major pitfalls.[33] In the context of perpetual motion machines such as the Orbo, Professor Eric Ash has argued at the BBC: "Denying [conservation of energy] would undermine not just little bits of science - the whole edifice would be no more.From the point of view of modern general relativity, the lab environment can be well approximated by Minkowski spacetime, where energy is exactly conserved.Given all the experimental evidence, any new theory (such as quantum gravity), in order to be successful, will have to explain why energy has appeared to always be exactly conserved in terrestrial experiments.[36] In some speculative theories, corrections to quantum mechanics are too small to be detected at anywhere near the current TeV level accessible through particle accelerators.[37] Some interpretations of quantum mechanics claim that observed energy tends to increase when the Born rule is applied due to localization of the wave function.

Energy conservationContinuum mechanicsFick's laws of diffusionMomentumClausius–Duhem (entropy)Solid mechanicsDeformationElasticitylinearPlasticityHooke's lawStressStrainFinite strainInfinitesimal strainCompatibilityBendingContact mechanicsfrictionalMaterial failure theoryFracture mechanicsFluid mechanicsFluidsStaticsDynamicsArchimedes' principleBernoulli's principleNavier–Stokes equationsPoiseuille equationPascal's lawViscosityNewtoniannon-NewtonianBuoyancyMixingPressureLiquidsAdhesionCapillary actionChromatographyCohesion (chemistry)Surface tensionAtmosphereBoyle's lawCharles's lawCombined gas lawFick's lawGay-Lussac's lawGraham's lawPlasmaRheologyViscoelasticityRheometryRheometerSmart fluidsElectrorheologicalMagnetorheologicalFerrofluidsBernoulliCauchyCharlesGay-LussacGrahamNewtonNavierPascalStokesTruesdellenergyisolated systemconservedchemical energyconvertedkinetic energydynamitepotential energyconservation of massspecial relativitymass–energy equivalencevery shortly after the Big Bangblack holesHawking radiationstationary-action principleNoether's theoremcontinuoustime translation symmetrygeneral relativityquantum mechanicsexpected valueobservedAncient philosophersThales of MiletusEmpedoclesfour rootsEpicurusSimon Stevinperpetual motionGalileoChristiaan Huygenslinear momentaHorologium OscillatoriumTorricelli's Principlecenter of gravitycenter of oscillationGottfried Leibnizmassesvelocityvis vivaphysicistsIsaac Newtonconservation of momentumelastic collisionPrincipialaws of motioninteractionist dualismcausal closureDaniel BernoulliJohannvirtual workHydrodynamicahydraulicD'Alembert's principleLagrangianHamiltonianEmilie du ChateletÉmilie du Châtelet