Kepler orbit

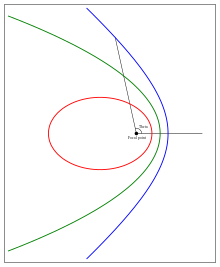

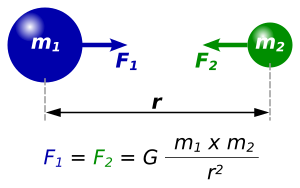

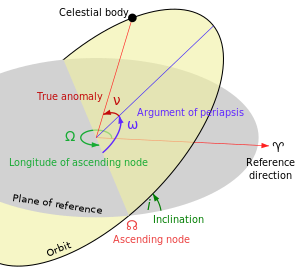

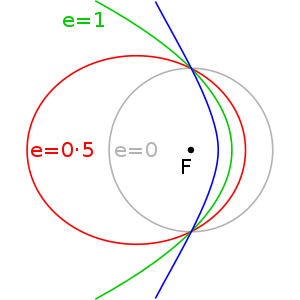

It considers only the point-like gravitational attraction of two bodies, neglecting perturbations due to gravitational interactions with other objects, atmospheric drag, solar radiation pressure, a non-spherical central body, and so on.As a theory in classical mechanics, it also does not take into account the effects of general relativity.As measurements of the planets became increasingly accurate, revisions to the theory were proposed.In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus published a heliocentric model of the Solar System, although he still believed that the planets traveled in perfectly circular paths centered on the Sun.[1] In 1601, Johannes Kepler acquired the extensive, meticulous observations of the planets made by Tycho Brahe.Kepler would spend the next five years trying to fit the observations of the planet Mars to various curves.The first law states: The orbit of every planet is an ellipse with the sun at a focus.More generally, the path of an object undergoing Keplerian motion may also follow a parabola or a hyperbola, which, along with ellipses, belong to a group of curves known as conic sections.This form of the equation is particularly useful when dealing with parabolic trajectories, for which the semi-major axis is infinite.[2] Between 1665 and 1666, Isaac Newton developed several concepts related to motion, gravitation and differential calculus.Where: Strictly speaking, this form of the equation only applies to an object of constant mass, which holds true based on the simplifying assumptions made below.Since Kepler's laws were well-supported by observation data, this consistency provided strong support of the validity of Newton's generalized theory, and unified celestial and ordinary mechanics.These laws of motion formed the basis of modern celestial mechanics until Albert Einstein introduced the concepts of special and general relativity in the early 20th century.By symmetry, the net gravitational force attracting a mass point towards a homogeneous sphere must be directed towards its centre.The shell theorem (also proven by Isaac Newton) states that the magnitude of this force is the same as if all mass was concentrated in the middle of the sphere, even if the density of the sphere varies with depth (as it does for most celestial bodies).From this immediately follows that the attraction between two homogeneous spheres is as if both had its mass concentrated to its center.Smaller objects, like asteroids or spacecraft often have a shape strongly deviating from a sphere.But the gravitational forces produced by these irregularities are generally small compared to the gravity of the central body.Planets rotate at varying rates and thus may take a slightly oblate shape because of the centrifugal force.Planetary motions in the Solar System can be computed with sufficient precision if they are treated as point masses.Even Jupiter's mass is less than the Sun's by a factor of 1047,[3] which would constitute an error of 0.096% in the value of α.Under these assumptions the differential equation for the two body case can be completely solved mathematically and the resulting orbit which follows Kepler's laws of planetary motion is called a "Kepler orbit".The orbits of the artificial satellites around the Earth are, with a fair approximation, Kepler orbits with small perturbations due to the gravitational attraction of the Sun, the Moon and the oblateness of the Earth.In high accuracy applications for which the equation of motion must be integrated numerically with all gravitational and non-gravitational forces (such as solar radiation pressure and atmospheric drag) being taken into account, the Kepler orbit concepts are of paramount importance and heavily used.Each vector has three components, so the total number of values needed to define a trajectory through space is six.These elements are convenient in that of the six, five are unchanging for an unperturbed orbit (a stark contrast to two constantly changing vectors).are simply angular measurements defining the orientation of the trajectory in the reference frame, they are not strictly necessary when discussing the motion of the object within the orbital plane.Since the cross product of the position vector and its velocity stays constant, they must lie in the same plane, orthogonal toAs by definition of p one has this can be written For a hyperbolic orbit one uses the hyperbolic functions for the parameterisation for which one has and the angular momentum H is Integrating with respect to time t gets i.e. To find what time t that corresponds to a certain true anomalythe Kepler orbit corresponding to the solution of this initial value problem can be found with the following algorithm: Define the orthogonal unit vectorsis a small "perturbing force" due to for example a faint gravitational pull from other celestial bodies.

celestial mechanicsJohannes Keplerellipseparabolahyperbolaorbital planestraight lineperturbationsatmospheric dragsolar radiation pressuresphericaltwo-body problemKepler problemclassical mechanicsgeneral relativityparametrizedorbital elementsbarycentergeocentricAristotlePtolemyepicycleNicolaus CopernicusheliocentricSolar SystemTycho Brahelaws of planetary motionconic sectionssemi-major axiseccentricitytrue anomalyperiapsisIsaac NewtonPrincipialaws of motionlaw of universal gravitationaccelerationgravitational constantpoint massproportionalAlbert Einsteinspecialgeneralastronomyastrodynamicstwo body systemshell theoremasteroidsspacecraftinertial reference frameunit vectorstandard gravitational parametersJupiterMercuryKeplerian elementsSemimajor axisInclinationLongitude of the ascending nodeArgument of periapsismean anomalyspecific relative angular momentumplane curveordinary differential equationconic sectionorbit determinationeccentric anomalyhyperbolic functionsATAN2(y,x)double precisionFORTRANinitial value problemOsculating orbiteccentricity vectorKepler's laws of planetary motionElliptic orbitHyperbolic trajectoryParabolic trajectoryRadial trajectoryOrbit modelingCopernicus, NicolausKepler conjectureKepler triangleKepler's equationKepler's SupernovaMysterium CosmographicumDe Stella NovaAstronomia novaEpitome Astronomiae CopernicanaeHarmonices MundiRudolphine TablesSomniumDie Harmonie der WeltKatharina KeplerJakob BartschKeplerKepler space telescopeJohannes Kepler ATVAstronomers MonumentList of namesakesorbitsCaptureCircularEllipticalHighly ellipticalEscapeHorseshoeInclinedNon-inclinedLagrange pointOsculatingParkingPrograde / RetrogradeSynchronousTransfer orbitGeosynchronousGeostationaryGeostationary transferGraveyardHigh EarthLow EarthMedium EarthMolniyaNear-equatorialOrbit of the MoonSun-synchronousTransatmospheric