Kepler conjecture

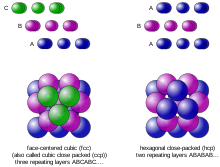

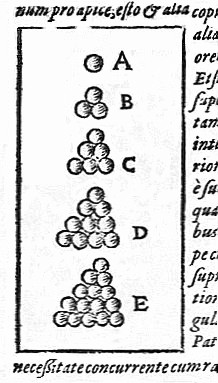

In 1998, Thomas Hales, following an approach suggested by Fejes Tóth (1953), announced that he had a proof of the Kepler conjecture.[1] Imagine filling a large container with small equal-sized spheres: Say a porcelain gallon jug with identical marbles.[2] However, a higher density can be achieved by carefully arranging the marbles as follows: At each step there are at least two choices of how to place the next layer, so this otherwise unplanned method of stacking the spheres creates an uncountably infinite number of equally dense packings.He had started to study arrangements of spheres as a result of his correspondence with the English mathematician and astronomer Thomas Harriot in 1606.Fejes Tóth (1953) showed that the problem of determining the maximum density of all arrangements (regular and irregular) could be reduced to a finite (but very large) number of calculations.[5] Following the approach suggested[6] by László Fejes Tóth, Thomas Hales, then at the University of Michigan, determined that the maximum density of all arrangements could be found by minimizing a function with 150 variables.Despite the unusual nature of the proof, the editors of the Annals of Mathematics agreed to publish it, provided it was accepted by a panel of twelve referees.In January 2003, Hales announced the start of a collaborative project to produce a complete formal proof of the Kepler conjecture.

Johannes Keplermathematicaltheoremsphere packingEuclidean spacespheresaverage densityface-centered cubichexagonal close packingThomas Halesproof by exhaustionIsabelleHOL LightForum of Mathematics, PiThomas HarriotSir Walter Raleighatomic theoryCarl Friedrich GausslatticeDavid Hilberttwenty three unsolved problems of mathematicsHilbert's eighteenth problemLászló Fejes TóthfiniteClaude Ambrose RogersUniversity of Michiganlinear programminggigabytesAnnals of MathematicsFulkerson Prize for outstanding papers in the area of discrete mathematicsautomated proof checkingForum of Mathematicscircle packingDelaunay triangulationhoneycomb conjectureDodecahedral conjectureVoronoi polyhedronMorgan PrizeKelvin structureWeaire–Phelan structureMaryna ViazovskaUlam's packing conjecturepacking densityHales, ThomasHales, Thomas C.The Mathematical IntelligencerSingh, SimonGoogle CodeDiscrete & Computational GeometryJournal of the American Mathematical SocietyBibcodeKlarreich, EricaThe Pursuit of Perfect PackingGauss, Carl F.Göttingische gelehrte AnzeigenNotices of the American Mathematical SocietyMathematische ZeitschriftProceedings of the London Mathematical SocietySzpiro, George G.John Wiley & SonsFejes Tóth, L.Springer-VerlagWeisstein, Eric W.MathWorldWayback MachineKepler's laws of planetary motionKepler orbitKepler triangleKepler's equationKepler's SupernovaMysterium CosmographicumDe Stella NovaAstronomia novaEpitome Astronomiae CopernicanaeHarmonices MundiRudolphine TablesSomniumDie Harmonie der WeltKatharina KeplerJakob BartschKeplerKepler space telescopeJohannes Kepler ATVAstronomers MonumentList of namesakes