Galileo project

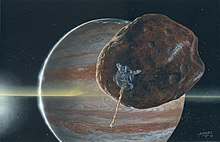

Most engineers regarded this solution as inelegant and planetary scientists at JPL disliked it because it meant that the mission would take months or even years longer to reach Jupiter.[24] The United States Congress approved funding for the Jupiter Orbiter Probe on July 19, 1977,[25] and JOP officially commenced on October 1, 1977, the start of the fiscal year.It was also interested in the manner in which JPL was designing Galileo to withstand the intense radiation of the magnetosphere of Jupiter, as this could be used to harden satellites against the electromagnetic pulse of nuclear explosions.On February 6, 1981 Strom Thurmond, the President pro tem of the Senate, wrote directly to David Stockman, the director of the OMB, arguing that Galileo was vital to the nation's defense.[69] Activists remembered the crash of the Soviet Union's nuclear-powered Kosmos 954 satellite in Canada in 1978, and the Challenger disaster, while it did not involve nuclear fuel, raised public awareness about spacecraft failures.If the Galileo/IUS combination fell free from the orbiter at 27,000 meters (90,000 ft), the RTGs would fall to Earth without melting, and drop into the Atlantic Ocean about 240 kilometers (150 mi) from the Florida coast.There were fears that the trucks might be hijacked by anti-nuclear activists or terrorists after the plutonium, so the route was kept secret from the drivers beforehand, and they drove through the night and the following day and only stopped for food and fuel.[77] Last-minute efforts by three environmental groups (the Christic Institute, the Florida Coalition for Peace and Justice and the Foundation on Economic Trends) to halt the launch were rejected by the District of Columbia Circuit on technical grounds rather than the merits of the case, but in a concurring opinion, Chief Justice Patricia Wald wrote that while the legal challenge was not frivolous, there was no evidence of the plaintiffs' claim that NASA had acted improperly in compiling the mission's environmental assessment.These included strong absorption of light at the red end of the visible spectrum (especially over continents) by chlorophyll in photosynthesizing plants; absorption bands of molecular oxygen as a result of plant activity; infrared bands caused by the approximately 1 micromole per mole of methane (a gas which must be replenished by volcanic or biological activity) in the atmosphere; and modulated narrowband radio wave transmissions uncharacteristic of any known natural source.[96] En route to Galileo's second gravity-assist flyby of Earth, the spacecraft flew over the lunar north pole on December 8, 1992, at an altitude of 110,000 kilometers (68,000 mi).The north pole had been photographed before, by Mariner 10 in 1973, but Galileo's cameras, with their 1.1 kilometers (0.68 mi) per pixel imagery, provided new information about a region that still held some scientific mysteries.The Table Mountain site used a Nd:YAG laser operating at a frequency-doubled wavelength of 532 nm, with a repetition rate of 15 to 30 Hertz and a pulse power full width at half maximum (FWHM) in the tens of megawatts range, which was coupled to a 0.6 m (2.0 ft) Cassegrain reflector telescope for transmission to Galileo.[112] Using compression, the arraying of several Deep Space Network antennas, and sensitivity upgrades to the receivers used to listen to Galileo's signal, data throughput was increased to a maximum of 160 bits per second.[114][115] The data collected on Jupiter and its moons were stored in the spacecraft's onboard tape recorder, and transmitted back to Earth during the long apoapsis portion of the probe's orbit using the low-gain antenna.[124] While Gaspra has plenty of small craters—over 600 of them ranging in size from 100 to 500 meters (330 to 1,640 ft)—it lacks large ones, hinting at a relatively recent origin,[120] although it is possible that some of the depressions were eroded craters.[138][139][140] The failure of Galileo's high-gain antenna meant that data storage to the tape recorder for later compression and playback was crucial in order to obtain any substantial information from the flybys of Jupiter and its moons.Most robotic spacecraft respond to failures by entering safe mode and awaiting further instructions from Earth, but this was not possible for Galileo during the arrival sequence due to the great distance and consequent long turnaround time.[144] The descent probe entered Jupiter's atmosphere, defined for the purpose as being 450 kilometers (280 mi) above the 1-bar (15 psi) pressure level,[147] without any braking at 22:04 UTC on December 7, 1995.[149][150] The rapid flight through the atmosphere produced a plasma with a temperature of about 14,000 °C (25,200 °F), and the probe's carbon phenolic heat shield lost more than half of its mass, 80 kilograms (180 lb), during the descent.Normally it took seven to ten days to diagnose and recover from a safe mode incident; this time the Galileo Project team at JPL had nineteen hours before the encounter with Io.Not all of the planned activities could be carried out, but Galileo obtained a series of high-resolution color images of the Pillan Patera, and Zamama, Prometheus, and Pele volcanic eruption centers.Nonetheless, the flyby was successful, with Galileo's NIMS and SSI camera capturing an erupting volcano that generated a 32-kilometer (20 mi) long plume of lava that was sufficiently large and hot to have also been detected by the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility atop Mauna Kea in Hawaii.The safe mode event also caused a loss of tape playback time, but the project managers decided to carry over some Io data into orbit G28, and play it back then.[182][183] After examining the magnetometer results, planetary scientist Margaret G. Kivelson, announced that Io had no intrinsic magnetic field, which meant that its molten iron core did not have the same convective properties as that of Earth.[207] On December 11, 2013, NASA reported, based on results from the Galileo mission, the detection of "clay-like minerals" (specifically, phyllosilicates), often associated with organic materials, on the icy crust of Europa.Subsequent analysis of Galileo data and work by amateur and professional astronomers showed that Delta Velorum is the brightest known eclipsing binary, brighter at maximum than Algol.The SSI camera began producing totally white images when the spacecraft was hit by the exceptional Bastille Day coronal mass ejection in 2000, and did so again on subsequent close approaches to Jupiter.[238] The most severe effects of the radiation were current leakages somewhere in the spacecraft's power bus, most likely across brushes at a spin bearing connecting rotor and stator sections of the orbiter.About 10 minutes after the closest approach of the Amalthea flyby, Galileo stopped collecting data, shut down all of its instruments, and went into safe mode, apparently as a result of exposure to Jupiter's intense radiation environment.Given the (admittedly slim) prospect of life on Europa, scientists Richard Greenberg and Randall Tufts proposed that a new standard be set of no greater chance of contamination than that which might occur naturally by meteorites.

Galileo · Jupiter · Earth · Venus · 951 Gaspra · 243 Ida

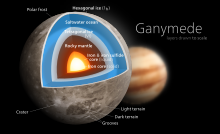

Galileo · Jupiter · Io · Europa · Ganymede · Callisto

Galileo (spacecraft)Galileo (satellite navigation)The Galileo ProjectProject GalileoJupiterCOSPAR IDSATCAT no.Jet Propulsion LaboratoryMesserschmitt-Bölkow-BlohmGeneral ElectricHughes Aircraft CompanySpace ShuttleAtlantisSTS-34KennedyLC-39B951 Gaspra243 IdaOrbiterLarge Strategic Science MissionsVoyager 1Cassini–Huygensits moonsSolar SystemGalileo GalileiGalileo spacecraftatmospheric entrygravity assistflybysatmosphereasteroidasteroid moonDactylComet Shoemaker–Levy 9ammoniavolcanismplasmaEuropasaltwaterGanymedeCallistomagnetic fieldexospheresring systemimpact eventsmagnetospherecontaminatingNational Aeronautics and Space AdministrationPlanetary flybylanderPioneer 10Pioneer 11Ames Research CenterSaturnVoyager 2John R. CasaniVoyagerheat shieldMarinerattitude control systemgyroscopesnitrogenCanopusstar trackerinertial reference unitaccelerometerTitan IIIECentaurspace tuglow Earth orbitUnited States Air Forcesolid-fueledInertial Upper StageBoeinggravity-assistfiscal yearHubble Space TelescopeSenatorWilliam ProxmireUnited States CongressGalilean moonsspacecraftatmospheric probeSpace Shuttle external tankSpace Shuttle orbiterSpace Shuttle main enginesColumbiaRobert A. FroschNASA AdministratorCentaur G PrimeSan Diego Air and Space Museumliquid hydrogenOffice of Management and Budgetattitudeground stationsnuclear weaponsanti-satellite weaponsmagnetosphere of Jupiterelectromagnetic pulseStrom ThurmondPresident pro tem of the SenateDavid StockmanJohn M. FabianDavid M. WalkerShuttle-Centaur29 Amphitrite1219 Britta1972 Yi XingJames M. Beggsslip ringschlorofluorocarbonread disturbPasadena, CaliforniaKennedy Space CenterFloridaSTS-61-Ggeneral-purpose heat source radioisotope thermoelectric generatorsplutonium-238lithium–sulfur batterymass spectrometerheliumwhistlerhigh-energy particlecosmicheavy ionnear-infrared mapping spectrometer