HMNB Devonport

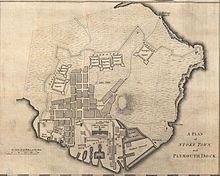

FOST, the training hub of the front-line Fleet, is also based there, as is the Royal Navy's Amphibious Centre of Excellence (at RM Tamar).The base employs 2,500 service personnel and civilians, supports circa 400 local firms and contributes approximately 10% to the income of Plymouth.[25] Operational vessels are provided with 'in-service engineering maintenance support' from the yard, dry docks are available to 'maintain, refit, convert and modernise sophisticated modern surface warships' and specialised workshops enable complex systems to be 'removed, overhauled, tested and installed'.[27] The project is described as 'a major infrastructure refurbishment of the nuclear licensed docking and berthing facilities at the dockyard' to meet the evolving requirements of the Royal Navy.[31] The National Audit Office in 2019 stated that the costs of laid up storage of all nuclear submarines had reached £500 million,[32] and they represent a liability of £7.5 billion.[43] Phase 3, the westernmost area extending to the waterfront, encompasses three 18th-century dry docks and several listed buildings; it was being offered for sale on a lease of up to 295 years.[43] Devonport Naval Heritage Centre, a volunteer-run maritime museum, is currently housed within two listed buildings in the Oceansgate area of the yard.[43] Proposed developments include expansion of Oceansgate beyond its current footprint, construction of a new factory for Princess Yachts and the building of a new Innovation Centre and 'Mobility Hub'[43] (described elsewhere as a 'huge multi-storey car park').Eventually it is hoped that the Freeport with its tax advantages will enable 'defence and other contractors to invest and bring back into productive and sustainable use dormant waterfront spaces [...] which, for the time being, must remain "behind the wire" [i.e. within the MOD restricted area]'.[52] Previously the Navy Board had relied upon timber as the major building material for dry docks, which resulted in high maintenance costs and was also a fire risk.[53] Dummer wished to ensure that naval dockyards were efficient working units that maximised available space, as evidenced by the simplicity of his design layout at Plymouth Dock.He introduced a centralised storage area (the quadrangular Great Storehouse) alongside the basin, and a logical positioning of other buildings around the yard.Around this time the small cove on the south side of the dockyard was partially reclaimed to create an enclosed mast pond and ground which was used for storing timber.[55] (Slipways were used for shipbuilding, but the main business of the eighteenth-century yard was the repair, maintenance and equipping of the fleet, for which the dry docks and basin were used).[63] Initially used for the manufacture of anchors and smaller metal items, it would later be expanded to fashion the iron braces with which wooden hulls and decks began to be strengthened; as such, it provided a hint of the huge change in manufacturing technology that would sweep the dockyards in the nineteenth century as sail began to make way for steam, and wood for iron and steel.[65] The South Yard was drastically impacted by aerial bombardment during the Second World War: by the end of 1942, 85% of its buildings had been either heavily damaged or destroyed.[59] Provision of ships' armaments was not the responsibility of the Navy but of the independent Board of Ordnance, which already had a wharf and storage facility in the Mount Wise area of Plymouth.(In the mid-19th century, to make room for the dockyard's expansion into Keyham, the gunpowder magazines were relocated to Bull Point, north of Weston Mill Lake).[73] On higher ground behind the wharf itself is a contemporary terrace of houses for officers (1720), built from stone rubble excavated during the yard's construction.Two stationary steam engines drove line shafts and heavy machinery, and the multiple flues were drawn by a pair of prominent chimneys.5 Basins (of 10 and 35 acres respectively), linked by a very large lock-cum-dock (the North Lock), 730 ft in length, alongside three more dry docks of a similar size (Nos.[80] At the northernmost end of the site the north-west promontory, together with the wharves facing on to Weston Mill Lake, functioned as a vast coaling yard for the steam-powered fleet.9 and 10 dry docks were strengthened and reconfigured so as to be able to accommodate the much larger Vanguard-class submarines, which entered into service from that year;[3] the work was completed by Carillion in 2002.5 Basin, land around Weston Mill Lake was reclaimed in the 1970s and the following decade the area (including the former coaling wharves) was repurposed to provide frigate berths for the Type 22 fleet.[88] In 2005 a sizeable area of the historic town centre of Devonport, which had been annexed after the war and was known as the South Yard Enclave, was released from MOD ownership.A few surviving buildings have been restored, most notably the Grade II listed Victorian former Market Hall[91] (which had been used as a sale store for the Naval Supply and Transport Service).[101] The nuclear-powered submarine HMS Courageous, used in the Falklands War, is preserved in North Yard as a museum ship, managed by the Heritage Centre (although it is currently closed to visitors until further notice).[111] Another explanation is that the name came from the Hindi word for a yard (36 inches), "guz", (also spelled "guzz", at the time) which entered the Oxford English Dictionary,[112] and Royal Navy usage,[113] in the late 19th century, as sailors used to regularly abbreviate "The Dockyard" to simply "The Yard", leading to the slang use of the Hindi word for the unit of measurement of the same name.A serving Royal Navy officer, usually of rear-admiral rank, was appointed as admiral-superintendent of the dockyard; however, the post was sometimes held by a commodore-superintendent or even a vice-admiral.Included:[123][119] On 30 December 1970, Vice-Admiral J R McKaig was appointed as Port Admiral, His Majesty's Naval Base, Devonport, and Flag Officer, Plymouth.

Devonport Naval BasePlymouthEnglandMinistry of DefenceNavy CommandRoyal NavyPlymouth BlitzHMNB ClydeHMNB Portsmouthnaval baseWestern EuropeDevonportRoyal Navy DockyardEdmund Dummerdry dockHMS ScyllaRM TamarprivatisedBabcock International GroupDevonport Management LimitedHMS VividHMS Drakecommand structureRoyal Naval Reservebasinsbut there is no 13 DockCommodore (RN)Royal MarineHMS TriumphType 45 destroyersAlbion-class assault shipsType 23 class frigatesDefence SecretaryType 26 frigatesFormer HMS OceanHMS Albionlanding platform dockHMS BulwarkHMS NorthumberlandHMS RichmondHMS PortlandHMS SomersetHMS KentHMS SutherlandHMS St AlbansHMS Iron DukePortsmouth FlotillaHMS TalentHMS TriumphHMS MagpieHMS ScottHMS ProtectorRFA ArgusRFA Wave RulerSeaforth DocksRFA Wave KnightFleet Operational Standards and TrainingSea-classHMS Vivid47 Commando (Raiding Group) Royal Marines539 Assault SquadronHaslerSouthern Diving Group RNDefence EstatesMinistry of Defence PoliceChathamRosythnuclear submarinesHMS ConquerorHMS CourageousHMS SceptreHMS SpartanHMS SplendidHMS SovereignHMS SuperbHMS TirelessHMS TorbayHMS TrafalgarHMS TurbulentHMS ValiantHMS WarspitePublic Accounts CommitteeNational Audit OfficeHMS ScyllaPlymouth City CouncilCity DealFreeportPrincess YachtssuperyachtsEnterprise ZoneDevonport Naval Heritage Centremaritime museumCremyllscrieve boardlanding craftbusiness planWilliam IIIEnglish ChannelSurveyor of the NavyCattewaterHamoazeRiver TamarStoke Damerelfirst-ratewet dockrope-housesmitherythe BlitzBartonPlymouth DockThomas MiltonreclaimedNicholas Pocockslipwaysdry docksreclaimboathouseThomas SladepedimentedEdward HollNicholas CondyHMS TalaveraImogeneHMS MindendreadnoughtsMachine shops