Andromeda (mythology)

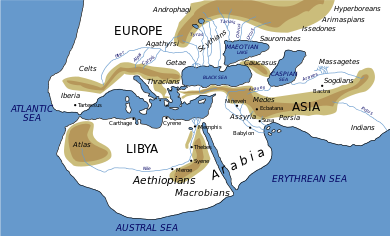

When Cassiopeia boasts that she (or Andromeda) is more beautiful than the Nereids, Poseidon sends the sea monster Cetus to ravage the coast of Aethiopia as divine punishment.[14] The myth of Andromeda was represented in the art of ancient Greece and of Rome in media including red-figure pottery such as pelike jars,[15] frescoes,[16] and mosaics.[21] Conon places the story in Joppa (Iope or Jaffa, on the coast of modern Israel), and makes Andromeda's uncles Phineus and Phoinix rivals for her hand in marriage; her father Cepheus contrives to have Phoinix abduct her in a ship named Cetos from a small island she visits to make sacrifices to Aphrodite, and Perseus, sailing nearby, intercepts and destroys Cetos and its crew, who are "petrified by shock" at his bravery.Viewing the fainter stars visible to the naked eye, the constellations are rendered as a maiden (Andromeda) chained up, facing or turning away from the ecliptic; a warrior (Perseus), often depicted holding the head of Medusa, next to Andromeda; a huge man (Cepheus) wearing a crown, upside down with respect to the ecliptic; a smaller figure (Cassiopeia) next to the man, sitting on a chair; a whale or sea monster (Cetus) just beyond Pisces, to the south-east; the flying horse Pegasus, who was born from the stump of Medusa's neck after Perseus had decapitated her; the paired fish of the constellation Pisces, that in myth were caught by Dictys the fisherman who was brother of Polydectes, king of Seriphos, the place where Perseus and his mother Danaë were stranded.[26] William Morris retells the story of Perseus and Andromeda in his epic 1868 poem The Earthly Paradise, in the section April: The Doom of King Acrisius.In the parody, Mnesilochus is shaved and dressed as a woman to gain entrance to the women's secret rites, held in honour of the fertility goddess Demeter.The play, a pièce à machines, presented to King Louis XIV of France and performed by the Comédiens du Roi, the royal troupe, had enormous and lasting success, continuing in production until 1660, to Corneille's surprise.Corneille chose to present Andromeda fully-clothed, supposing that her nakedness had been merely a painterly tradition; Knutson comments that in so doing, "he unintentionally broke the last link with the early erotic myth.[5] Written for King Louis XIV, it has been described as Lully's "greatest creation [...] considered the crowning achievement of 17th century French music theatre.The historian and filmmaker Henry Louis Gates Jr. criticizes both the original film and its remake for using white actresses to portray the Ethiopian princess Andromeda.Kimathi Donkor comments that none of the three films provide any "hint of the disruptive racial dilemma posed by the classical setting of Ethiopia",[51] preferring instead to continue the Western art tradition of "a hegemonic white visual space denying Ovid's mythography of black beauty."[51] The legend of Saint George and the Dragon, in which a courageous knight rescues a princess from a monster (with clear parallels to the Andromeda myth), became a popular subject for art in the Late Middle Ages, and artists drew from both traditions.One result is that Perseus is often shown with the flying horse Pegasus when fighting the sea monster, even though classical sources consistently state that he flew using winged sandals.[1] Andromeda, and her role in the popular myth of Perseus, has been the subject of numerous ancient and modern works of art, where she is represented as a bound and helpless, typically beautiful, young woman placed in terrible danger, who must be saved through the unswerving courage of a hero who loves her.[55] Apart from oil on canvas, artists have used a variety of materials to depict the myth of Andromeda, including the sculptor Domenico Guidi's marble, and François Boucher's etching.Félix Vallotton's 1910 Perseus Killing the Dragon is one of several paintings, such as his 1908 The Rape of Europa, in which the artist depicts human bodies using a harsh light which makes them appear brutal.[61] By the 1st century BC a rival location for Andromeda's story had become established: an outcrop of rocks near the ancient port city of Joppa, as reported by Pomponius Mela,[62] the traveller Pausanias,[63] the geographer Strabo,[64] and the historian Josephus.[65] A case has been made that this new version of the myth was exploited to enhance the fame and serve the local tourist trade of Joppa, which also became connected with the biblical story of Jonah and yet another huge sea creature.[68] The art historian Elizabeth McGrath discusses the tradition, as promoted by the influential Roman poet Ovid, that Andromeda was a dark-skinned woman of either Ethiopian or Indian origin.And often white pigeons mate with other hues, and the dark turtledove's loved by emerald birds";[71] the Latin word fuscae Ovid uses here for 'dark Andromeda' refers to the colour black or brown.[77] Heliodorus of Emesa follows Philostratus in describing Andromeda as light-skinned in contrast to the clearly dark-skinned Aethiopians; in his Aethiopica, Queen Persinna of Aethiopia gives birth to an inexplicably white girl, Chariclea.[78] Artworks in the modern era continue to portray Andromeda as fair-skinned, regardless of her stated origins; only a small minority of artists, such as an engraving after Abraham van Diepenbeeck, have chosen to show her as dark."[4] As for the bondage, Munich notes that the Victorian critic John Ruskin attacked male exploitation of what she calls "suffering nudes as subjects for titillating pictures."[4] In the view of Marilynn Desmond and Pamela Sheingorn, Christine de Pizan's Ovide moralisé presents the bound Andromeda in a miniature image as "the object of desire"."[81] The scholar of literature Harold Knutson describes the story as having a "disturbing sensuality", which together with the evident injustice of Andromeda's "undeserved sacrifice, create a curiously ambiguous effect".

Perseus and Andromeda (disambiguation)AethiopiaPompeiiCepheusCassiopeiaPerseusPersesHeleusAlcaeusSthenelusElectryonMestorGorgophoneGreek mythologyAncient GreekromanizedNereidsPoseidonsea monsterdivine punishmenthuman sacrificeMedusapetrifiesclassical antiquityGreek heroprincess and dragonRenaissanceMetamorphosesconstellationsAndromedaSaint George and the DragonPegasusBellerophonwinged horseLudovico Ariostoepic poemOrlando Furiosowhite womandark-skinnedmale superioritysubmissivebondagesorceresshubrisoraclesacrificeswinged sandalsGorgonPhineusSeriphosDanaëAcrisiusTirynsApollodorusMycenaeEurystheusAtreusHeraclesAlcmeneCatasterismiAthenaconstellation Andromedaart of ancient Greeceof Romered-figure potterypelikefrescoesmosaicsRoman villa in BoscotrecaseCorinthianamphoraApulianred-figure vaseFrescoBoscotrecaseZeugmaHyginussatiristLucianByzantineJohn TzetzesIsraelAphroditeconstellationUrania's MirrorSidney HallNorthern skyPtolemyAndromeda GalaxyeclipticPiscesDictysfishermanPolydectesGeorge Chapmanheroic coupletsRobert Carr, 1st Earl of SomersetFrances HowardallegoryEarl of EssexastrologicalVenus and MarsKing JamesAngelicaSaracenRuggieroJohn KeatssonnetWilliam MorrisThe Earthly ParadiseGerard Manley HopkinsCharles KingsleyhexameterCyril RoothamallegoricallyGustave DoréMoby-DickHerman MelvilleGuido ReniWilliam HogarthJules LaforgueCarlton DaweRobert Nichols'sshort storysatiricallyThe Sea, the Sea