Ancient Greece

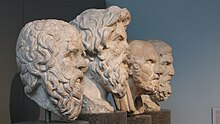

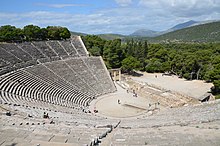

The unification of Greece by Macedon under Philip II and subsequent conquest of the Achaemenid Empire by Alexander the Great spread Hellenistic civilisation across the Middle East.For this reason, Classical Greece is generally considered the cradle of Western civilisation, the seminal culture from which the modern West derives many of its founding archetypes and ideas in politics, philosophy, science, and art.Classical antiquity in Greece was preceded by the Greek Dark Ages (c. 1200 – c. 800 BC), archaeologically characterised by the protogeometric and geometric styles of designs on pottery.Finally, Late Antiquity refers to the period of Christianisation during the later 4th to early 6th centuries AD, consummated by the closure of the Academy of Athens by Justinian I in 529.[27] Other alliances in the sixth century included those between Elis and Heraea in the Peloponnese; and between the Greek colony Sybaris in southern Italy, its allies, and the Serdaioi.[43] The Athenian failure to regain control of Boeotia at Delium and Brasidas' successes in northern Greece in 424 improved Sparta's position after Sphakteria.[51] Following the Athenian surrender, Sparta installed an oligarchic regime, the Thirty Tyrants, in Athens,[50] one of a number of Spartan-backed oligarchies which rose to power after the Peloponnesian war.[53] The first half of the fourth century saw the major Greek states attempt to dominate the mainland; none were successful, and their resulting weakness led to a power vacuum which was eventually filled by Macedon under Philip II and then Alexander the Great.[54] In the immediate aftermath of the Peloponnesian war, Sparta attempted to extend their own power, leading Argos, Athens, Corinth, and Thebes to join against them.Though Thebes had won the battle, their general Epaminondas was killed, and they spent the following decades embroiled in wars with their neighbours; Athens, meanwhile, saw its second naval alliance, formed in 377, collapse in the mid-350s.The first Hellenistic kings were previously Alexander's generals, and took power in the period following his death, though they were not part of existing royal lineages and lacked historic claims to the territories they controlled.[67] Meanwhile, the Seleucid kingdom gave up territory in the east to the Indian king Chandragupta Maurya in exchange for war elephants, and later lost large parts of Persia to the Parthian Empire.[citation needed] For much of the period until the Roman conquest, these leagues were at war, often participating in the conflicts between the Diadochi (the successor states to Alexander's empire).In the south lay the Peloponnese, consisting of the regions of Laconia (southeast), Messenia (southwest), Elis (west), Achaia (north), Korinthia (northeast), Argolis (east), and Arcadia (center).The second form was in what historians refer to as emporia; trading posts which were occupied by both Greeks and non-Greeks and which were primarily concerned with the manufacture and sale of goods.Modern Syracuse, Naples, Marseille and Istanbul had their beginnings as the Greek colonies Syracusae (Συράκουσαι), Neapolis (Νεάπολις), Massalia (Μασσαλία) and Byzantion (Βυζάντιον).[81] Thus, the major peculiarities of the ancient Greek political system were its fragmented nature (and that this does not particularly seem to have tribal origin), and the particular focus on urban centers within otherwise tiny states.Later in the Classical period, the leagues would become fewer and larger, be dominated by one city (particularly Athens, Sparta and Thebes); and often poleis would be compelled to join under threat of war (or as part of a peace treaty).Even after Philip II of Macedon conquered the heartlands of ancient Greece, he did not attempt to annex the territory or unify it into a new province, but compelled most of the poleis to join his own Corinthian League.Inevitably, the domination of politics and concomitant aggregation of wealth by small groups of families was apt to cause social unrest in many poleis.In many cities a tyrant (not in the modern sense of repressive autocracies), would at some point seize control and govern according to their own will; often a populist agenda would help sustain them in power.At least in the Archaic period, the fragmentary nature of ancient Greece, with many competing city-states, increased the frequency of conflict but conversely limited the scale of warfare.This inevitably reduced the potential duration of campaigns, as citizens would need to return to their own professions (especially in the case of, for example, farmers).Casualties were slight compared to later battles, rarely amounting to more than five percent of the losing side, but the slain often included the most prominent citizens and generals who led from the front.The eventual triumph of the Greeks was achieved by alliances of city-states (the exact composition changing over time), allowing the pooling of resources and division of labor.The rise of Athens and Sparta as pre-eminent powers during this conflict led directly to the Peloponnesian War, which saw further development of the nature of warfare, strategy and tactics.They were followed by Socrates, one of the first philosophers based in Athens during its golden age whose ideas, despite being known by second-hand accounts instead of writings of his own, laid the basis of Western philosophy.The first geometrical, three-dimensional models to explain the apparent motion of the planets were developed in the 4th century BC by Eudoxus of Cnidus and Callippus of Cyzicus.[124] In the 2nd century BC Hipparchus of Nicea made a number of contributions, including the first measurement of precession and the compilation of the first star catalog in which he proposed the modern system of apparent magnitudes.In the East, Alexander the Great's conquests initiated several centuries of exchange between Greek, Central Asian and Indian cultures, resulting in Greco-Buddhist art, with ramifications as far as Japan.

Kingdom of

Ptolemy I Soter

Kingdom of

Cassander

Kingdom of

Lysimachus

Kingdom of

Seleucus I Nicator

Also shown on the map:

Carthage

(non-Greek)

Rome

(non-Greek)

The orange areas were often in dispute after 281 BC. The

Attalid dynasty

occupied some of this area. Not shown:

Indo-Greek Kingdom

.

Ancient GreekHistory of GreeceNeolithic GreecePelasgiansGreek Bronze AgeHelladic chronologyCycladicMinoanMyceneanGreek Dark AgesArchaic GreeceClassical GreeceHellenistic GreeceRoman GreeceMedieval GreeceByzantine GreeceFrankish and Latin statesEarly modern GreeceVenetian CreteVenetian Ionian IslandsOttoman GreeceModern GreeceSeptinsular RepublicWar of IndependenceFirst Hellenic RepublicKingdom of GreeceNational SchismSecond Hellenic Republic4th of August RegimeAxis occupationCollaborationist regimeFree GreeceCivil WarMilitary JuntaThird Hellenic RepublicAgricultureAlphabetConstitutionEconomyEthnonymsLanguageMilitaryAncient historyprehistoryNear EastDilmunBerbersAssyriaBabyloniaAmurruYamhadUrkeshMitanniHittitesPhrygiansUgaritCanaanPhoeniciaAlashiyaArameansIsrael and JudahSabaʾHimyarChaldeaUrartuPhrygiaAchaemenid EmpireSea PeoplesAnatoliaArabiaThe LevantMesopotamiaAegean CivilizationThraciansDaciansIllyriansArgaricTorreanNuragicTalaioticTartessosGuanchesEtruscansMigration PeriodBarbarian kingdomsGermanicsIberiaBritish IslesIllyriaThraciaCaucasusHorn of AfricaLand of PuntKerma kingdomMacrobiaKingdom of KushKingdom of AksumKingdom of SimienHarla kingdomBarbariaMosylonMundusTonikiAromataAvalitesSarapionEssinaNilotic PeoplesAfrican kingdomsNorth AfricaCarthageGaramantesNasamones chiefdomCyreneBlemmyesMassylii ConfederationNumidiaMauretaniaNobatiaKingdom of OuarsenisKingdom of the Vandals and AlansKingdom of CapsusKingdom of MasunaKingdom of the AurèsKingdom of MakuriaKingdom of Hodna