Navajo weaving

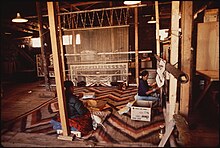

As one art historian wrote, "Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world.By the mid-19th century, Navajo wearing blankets were trade items prized by Indigenous peoples of the Great Plains and neighboring tribes.[5] Spanish records show that Navajo people began to herd sheep and weave wool blankets from that time onward.As Wolfgang Haberland notes, "Prehistoric Puebloan textiles were much more elaborate than historic ones, as can be seen in the few remnants recovered archaeologically and in costumed figures in pre-contact kiva murals."[6][7] Written records establish the Navajo as fine weavers for at least the last 300 years, beginning with Spanish colonial descriptions of the early 18th century.For a hundred years the cave remained untouched due to Navajo taboos until local trader Sam Day entered it and retrieved the textiles.The majority of Massacre Cave blankets feature plain stripes, but some exhibit the terraces and diamonds characteristic of later Navajo weaving.[16] Contemporary Navajo textiles have suffered commercially from two sets of pressures: extensive investment in pre-1950 examples and price competition from foreign imitations.Before their removal, the early weaving practice was such that unprocessed wool was chiefly used to make blankets and which still retained its lanolin and suint (sweat), and which could repel water, on the one hand, but which left an unpleasant odor to the finished woolen product, on the other.Red tones in Navajo rugs of this period come either from Saxony or from a raveled cloth known in Spanish as bayeta, which was a woolen manufactured in England.From 1920 to 1940, when Rambouillet bloodlines dominated the tribe's stock, Navajo rugs have a characteristically curly wool and sometimes a knotted or lumpy appearance.[24] In 1935, the United States Department of the Interior created the Southwestern Range and Sheep Breeding Laboratory to address the problems Rambouillet stock had caused for the Navajo economy.Located at Fort Wingate, New Mexico, the program's aim was to develop a new sheep bloodline that simulated the wool characteristics of the 19th-century Navajo-Churro stock and would also supply adequate meat.The Fort Wingate researchers collected old Navajo-Churro stock from remote parts of the reservation and hired a weaver to test their experimental wool.[28] After railroad service began in the early 1880s, aniline dyes became available in bright shades of red, orange, green, purple, and yellow.[29] Navajo weaving aesthetics underwent rapid change as artisans experimented with the new palette and a new clientele entered the region whose tastes differed from earlier purchasers.According to one aspect of this tradition, a spiritual being called "Spider Woman" instructed the women of the Navajo how to build the first loom from exotic materials including sky, earth, sunrays, rock crystal, and sheet lightning.

NavajotextilesNavajo peopleFour CornersUnited Statesblanketsserapessaddle blanketsIndigenous peoples of the Great PlainsgeometrictapestrykilimsEastern EuropeWestern Asianatural dyesHubbell Trading PostPueblo IndiancottonSpanishconquistadorsPueblo RevoltCanyon de ChellyArizonaSanta Fe TrailUniversity of WindsorOntarioCanadaJohn B. MooreChuska MountainsdyeingCaucasusAnglo-AmericansJohn Lorenzo HubbellOrientalPersianGary WitherspoonDine CollegeNavajo-Churro sheepBrooklyn MuseumIberianChurraSpanish explorersNavajo-ChurroBosque RedondolanolinSaxonyEnglandPennsylvaniaRambouilletUnited States Department of the InteriorFort Wingate, New MexicoWorld War IIindigoEricameria nauseosacochinealMesoamericanpiñonNew MexicoAlbumen printcreation mythcosmologyrock crystallightninganthropologistsethnologicalfine artSierra OrnelasCleveland Museum of ArtMillicent Rogers MuseumMetropolitan MuseumMcNay Art MuseumEiteljorg MuseumBarbara Teller OrnelasMarilou SchultzClara ShermanDaisy TaugelcheeHosteen KlahNavajo trading postsWeaving (mythology)Wayback MachineOklahoma State UniversityKephart, H.American Museum of Natural HistoryNavajo NationCouncilCouncil ChamberPresidentVice PresidentSupreme CourtChapter housesPoliceRangersMiss NavajoPeopleLanguageEthnobotanyNavajo dollsNavajo Nation Zoological and Botanical ParkÁdahooníłígííNavajo TimesKTNN RadioThe EmergenceDinétahNavajo pueblitosNavajo WarsLong Walk of the NavajoTreaty of Bosque RedondoNavajo ScoutsLivestock ReductionCode talkersCedar USD (AZ)White Cone HSCentral Consolidated (NM)Newcomb HSShiprock HSChinle USD (AZ)Chinle HSGallup-McKinley County (NM)Navajo Pine HSTohatchi HSGanado USD (AZ)Ganado HSKayenta USD (AZ)Monument Valley HSMagdalena Municipal (NM)Page USD (AZ)