Nationalist faction (Spanish Civil War)

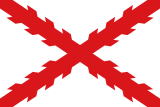

[6] The leaders of the rebel faction, who had already been denominated as 'Crusaders' by Bishop of Salamanca Enrique Pla y Deniel – and also used the term Cruzada for their campaign – immediately took a liking to it.In Spain the Francoist side was mainly supported by the predominantly conservative upper class, liberal professionals, religious organizations and land-owning farmers.It was mostly based in the rural areas where progressive political movements had made few inroads, such as great swathes of the Northern Meseta, including almost all of Old Castile, as well as La Rioja, Navarre, Alava, the area near Zaragoza in Aragon, most of Galicia, parts of Cáceres in Extremadura and many dispersed pockets in rural Andalusia where the local society still followed older traditional patterns and was yet comparably untouched by "modern" thought.[11] As a landowner and aristocrat, Primo de Rivera assured the upper classes that Spanish fascism would not get out of their control like its equivalents in Germany and Italy.[10] The Falange committed acts of violence before the war, including becoming involved in street brawls with their political opponents that helped to create a state of lawlessness that the right-wing press blamed on the republic to support a military uprising.[17] Under Franco's leadership, the Falange abandoned the previous anticlerical tendencies of José Antonio Primo de Rivera and instead promoted neotraditionalist National Catholicism, though it continued to criticize Catholic pacifism.[20] Gil-Robles attended in audience at the Nazi Party rally in Nuremberg and was influenced by it, henceforth becoming committed to creating a single anti-Marxist counterrevolutionary front in Spain.[20] Gil-Robles declared his intention to "give Spain a true unity, a new spirit, a totalitarian polity..." and went on to say "Democracy is not an end but a means to the conquest of the new state.[22] The CEDA failed to make the substantive electoral gains from 1931 to 1936 that were needed for it to form government which resulted in right-wing support draining from it and turning towards the belligerent Alfonsist monarchist leader José Calvo Sotelo.[14] The Carlists held a long history of violent opposition to Spanish liberalism, stemming back to 1833 when they launched a six-year civil war against the reformist regency of María Cristina de las dos Sicilias.Their proverbial cruelty and reckless behaviour were not random, but were part of a calculated plan of the Francoist military leaders in order to instill terror in the Republican defence lines.For several years after the war, Franco would have a squadron of Moorish troops act as his escort at public ceremonies as a reminder of the Army's importance in the Nationalist victory.[38] Italy's Fascist regime considered the threat of Bolshevism a real risk with the arrival of volunteers from the Soviet Union who were fighting for the Republicans.[45] Upon the outbreak of the civil war, Portuguese Prime Minister António de Oliveira Salazar almost immediately supported the National forces.[47] Among many influential Catholics in Spain, mainly composed of conservative traditionalists and people belonging to pro-monarchic groups, the religious persecution was squarely, and based on evidence probably rightly, mostly blamed on the government of the Republic.[50] Initially the Vatican held itself from declaring too openly its support of the rebel side in the war, although it had long allowed high ecclesiastical figures in Spain to do so and to define the conflict as a 'Crusade'.[51] Forsaken by the Western European powers, the republican side mainly depended on Soviet military assistance; this played into the hands of the portrayal in Francoist propaganda of the Spanish Republic as a 'Marxist' and godless state.

Francisco FrancoJosé SanjurjoEmilio MolaManuel Goded LlopisIdeologySpanish nationalismTotalitarianismAuthoritarian conservatismNational CatholicismPara-fascismFactionsFascismFalangismCarlismAnti-Catalan sentimentAlfonsismPolitical positionRight-wingfar-rightWhite TerrorMovimiento NacionalGermanyPortugalHoly SeeRepublican factionSecond Spanish RepublicSpanish Civil WarSpanish coup of July 1936Francoist SpainSpanishright-leaningManuel AzañaFalangemonarchistAlfonsistRenovación EspañolaCarlistTraditionalist Communionall the groups were mergedFET y de las JONSNationalistsdictator of SpainJoseph GoebbelsmaterielCrusadersBishop of SalamancaEnrique Pla y DenielpropagandafascistsOld CastileLa RiojaNavarreZaragozaAragonGaliciaCáceresExtremaduraAndalusiaFE de las JONSFalange EspañolafascistJosé Antonio Primo de RiveraMiguel Primo de Riveraanti-clericalJuntas de Ofensiva Nacional-SindicalistaRamiro Ledesma RamosFalange Española de las JONSManuel Hedilladecree of unification of the National political movementsFalange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONSpacifismcapitalismRaimundo Fernández-CuestaSpanish Confederation of Autonomous Right-wing GroupsJosé María Gil-Robles y QuiñonesNazi PartyJosé Calvo SoteloJuventudes de Acción PopularRequetésFrancisco Javier de BorbónKing of SpainManuel Fal Condéliberalismsix-year civil warMaría Cristina de las dos SiciliasAlfonso XIII of SpainSpanish Second RepublicAntonio GoicoecheaBenito MussolinicorporatistSotelo was kidnapped and assassinated by political opponentsInfante JuanBalaeresSpanish Military UnionArmy of AfricaRegularesFlag of the Spanish Moroccan ProtectorateMohamed Mezianefield armySpanish MoroccoRif WarSpanish Foreign Legionshock troopsMoroccanJunkers Ju 52Civil Guard (Spain)Sebastián PozasAviación NacionalSpanish NavyForeign involvement in the Spanish Civil WarFascist ItalyItalian military intervention in SpainBolshevismSoviet Unionexpeditionary forceCorpo Truppe VolontarieMario RoattaLittorioDio lo VuoleFiamme NereBlackshirtRoberto FarinacciSpanish National PartyGerman involvement in the Spanish Civil WarNazi GermanyCondor Legion