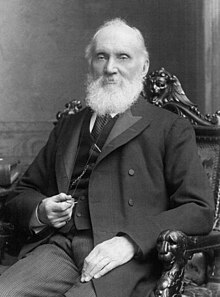

Lord Kelvin

The Thomson children were introduced to a broader cosmopolitan experience than their father's rural upbringing, spending mid-1839 in London, and the boys were tutored in French in Paris.[21] In the academic year 1839/1840, Thomson won the class prize in astronomy for his "Essay on the figure of the Earth" which showed an early facility for mathematical analysis and creativity.mount where Science guides; Go measure earth, weigh air, and state the tides; Instruct the planets in what orbs to run, Correct old Time, and regulate the sun; Thomson became intrigued with Joseph Fourier's Théorie analytique de la chaleur (The Analytical Theory of Heat).The book motivated Thomson to write his first published scientific paper[25] under the pseudonym P.Q.R., defending Fourier, which was submitted to The Cambridge Mathematical Journal by his father.[27] In the paper he made remarkable connections between the mathematical theories of thermal conduction and electrostatics, an analogy that James Clerk Maxwell was ultimately to describe as one of the most valuable science-forming ideas.[28] William's father was able to make a generous provision for his favourite son's education and, in 1841, installed him, with extensive letters of introduction and ample accommodation, at Peterhouse, Cambridge."[31] In 1845, he gave the first mathematical development of Michael Faraday's idea that electric induction takes place through an intervening medium, or "dielectric", and not by some incomprehensible "action at a distance".[32] On gaining the fellowship, he spent some time in the laboratory of the celebrated Henri Victor Regnault, at Paris; but in 1846 he was appointed to the chair of natural philosophy in the University of Glasgow.Thomson returned to critique Carnot's original publication and read his analysis to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in January 1849,[35] still convinced that the theory was fundamentally sound.[38] In final publication, Thomson retreated from a radical departure and declared "the whole theory of the motive power of heat is founded on ... two ... propositions, due respectively to Joule, and to Carnot and Clausius."[39] Thomson went on to state a form of the second law: It is impossible, by means of inanimate material agency, to derive mechanical effect from any portion of matter by cooling it below the temperature of the coldest of the surrounding objects.On 16 October 1854, George Gabriel Stokes wrote to Thomson to try to re-interest him in work by asking his opinion on some experiments of Faraday on the proposed transatlantic telegraph cable.Thomson sailed on board the cable-laying ship HMS Agamemnon in August 1857, with Whitehouse confined to land owing to illness, but the voyage ended after 380 miles (610 km) when the cable parted.It was not until Thomson convinced the board that using purer copper for replacing the lost section of cable would improve data capacity, that he first made a difference to the execution of the project.Though employed in an advisory capacity, Thomson had, during the voyages, developed a real engineer's instincts and skill at practical problem-solving under pressure, often taking the lead in dealing with emergencies and being unafraid to assist in manual work.Over the period 1855 to 1867, Thomson collaborated with Peter Guthrie Tait on a textbook that founded the study of mechanics first on the mathematics of kinematics, the description of motion without regard to force.Thomson may have unwittingly observed atmospheric electrical effects caused by the Carrington event (a significant geomagnetic storm) in early September 1859.During the 1880s, Thomson worked to perfect the adjustable compass to correct errors arising from magnetic deviation owing to the increased use of iron in naval architecture.Thomson's innovations involved much detailed work to develop principles identified by George Biddell Airy and others, but contributed little in terms of novel physical thinking.Writers sympathetic to the Navy, on the other hand, portray Thomson as a man of undoubted talent and enthusiasm, with some genuine knowledge of the sea, who managed to parlay a handful of modest ideas in compass design into a commercial monopoly for his own manufacturing concern, using his reputation as a bludgeon in the law courts to beat down even small claims of originality from others, and persuading the Admiralty and the law to overlook both the deficiencies of his own design and the virtues of his competitors'.In the Memoirs of the Roman Academy of Sciences for 1857 he published a description of his divided ring electrometer, based on the electroscope of Johann Gottlieb Friedrich von Bohnenberger.[64] Acknowledging his contribution to electrical standardisation, the International Electrotechnical Commission elected Thomson as its first president at its preliminary meeting, held in London on 26–27 June 1906.)[67][68] He contended that the laws of thermodynamics operated from the birth of the universe and envisaged a dynamic process that saw the organisation and evolution of the Solar System and other structures, followed by a gradual "heat death".[70] His calculations showed that the Sun could not have possibly existed long enough to allow the slow incremental development by evolution - unless it was heated by an energy source beyond the knowledge of Victorian era science.[78] Although his former assistant John Perry published a paper in 1895 challenging Kelvin's assumption of low thermal conductivity inside Earth, and thus showing a much greater age,[79] this had little immediate impact.Although he eventually paid off a gentleman's bet with Strutt on the importance of radioactivity in Earth's geology, he never publicly acknowledged this because he thought he had a much stronger argument restricting the age of the Sun to no more than 20 million years.In the winter of 1860–61 Kelvin slipped on the ice while curling near his home at Netherhall and fractured his leg, causing him to miss the 1861 Manchester meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and to limp thereafter.[98][99] The two "dark clouds" he was alluding to were confusion surrounding how matter moves through the aether (including the puzzling results of the Michelson–Morley experiment) and indications that the equipartition theorem in statistical mechanics might break down.In 1896 he refused an invitation to join the Aeronautical Society, writing "I have not the smallest molecule of faith in aerial navigation other than ballooning or of expectation of good results from any of the trials we hear of.[104] There is no evidence that Kelvin said this,[105][106] and the quote is instead a paraphrase of Albert A. Michelson, who in 1894 stated: "... it seems probable that most of the grand underlying principles have been firmly established ... An eminent physicist remarked that the future truths of physical science are to be looked for in the sixth place of decimals.

William Thomson (disambiguation)The Right HonourablePresident of the Royal SocietySir George StokesThe Lord ListerBelfastUnited Kingdom of Great Britain and IrelandScotlandLiberalLiberal UnionistJames ThomsonRoyal Belfast Academical InstitutionGlasgow UniversityPeterhouse, CambridgeJoule–Thomson effectJoule-Thomson ideal gas coefficientVoigt–Thomson lawThomson effectKelvin balanceKelvin's ballsKelvin's mirror galvanometerKelvin materialKelvin water dropperKelvin waveKelvin–Helmholtz instabilityKelvin–Helmholtz mechanismKelvin-Helmholtz luminosityKelvin-Planck statementKelvin's heat death paradoxKelvin–Helmholtz time scaleKelvin's minimum energy theoremKelvin conjectureKelvin structureKelvin foamKelvin functionsKelvin transformKelvin's circulation theoremKelvin–Stokes theoremKelvin bridgeKelvin sensingKelvin equationKelvin-Varley dividerKelvin wake patternZero KelvinKelvin probe force microscopeKelvin scanning probeAutomatic curb senderCable theoryDark night sky paradoxEarth's age paradoxDepth soundingDissipationGyrostatLaw of squaresFirst law of thermodynamicsSecond law of thermodynamicsEntropyHeat death of the universeMagnetic vector potentialMagnetoresistanceMaxwell's demonPiezoresistive effectSiphon recorderStationary phase approximationDark matterTide-predicting machineVortex theory of the atomCoining the term chiralityCoining the term thermodynamicsCoining the term kinetic energySmith's PrizeRoyal MedalKeith MedalMatteucci MedalAlbert MedalCopley MedalJohn Fritz MedalUniversity of GlasgowWilliam HopkinsLord RayleighWilliam Edward Ayrtonmathematical physicistprofessor of Natural Philosophymathematical analysislaws of thermodynamicsphysicsRoyal SocietypresidentHouse of Lordskelvinabsolute zeroFahrenheitHugh Blackburnelectrical telegraphtransatlantic telegraph projectknightedQueen VictoriacompassennobledIrish Home RuleCounty of AyrRiver KelvinHillheadGeorge EastmanEastman Kodakchancellor of the University of GlasgowHunterian MuseumJames Thomson (mathematician)James Thomson (engineer)William RankinethermodynamicsUlster ScotsGlasgowGermanyNetherlandsJames Thomson BottomleymeanderNeo-GothicGeorge Gilbert ScottLucianAncient GreekastronomyDavid ThomsoncopingAlexander PopeAn Essay on Man