History of the nude in art

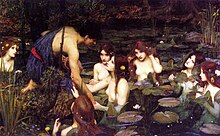

[41] As for the painting, of which we have received numerous samples thanks mainly to the excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum, despite their eminently decorative character, they offer great stylistic variety and thematic richness, with an iconography that goes from mythology to the most everyday scenes, including parties, dances and circus shows.Among the many scenes that decorate the walls of Pompeii and in which the nude is present, it is worth remembering: The Three Graces, Aphrodite Anadyomene, Invocation to Priapus, Cassandra abducted by Ajax, The Dancing Faun, Bacchante surprised by a satyr, The rape of the nymph Iphtima, Hercules recognizing his son Telephus in Arcadia, The centaur Chiron instructing the young Achilles, Perseus freeing Andromeda, The Aldobrandini Wedding, etc.This can be seen in Giovanni Bellini's Naked Young Woman in Front of a Mirror (1515), although the main initiator of this style was Giorgione, who was the first to structure the female nude within a general decorative scheme, as in his frescoes of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi (1507–1508, now disappeared), in his Pastoral Concert (1510) or in his Sleeping Venus (1507–1510), whose reclining posture has been copied ad nauseam.In his decoration of the Venetian Doge's Palace (1560–1578) he made an authentic apotheosis of the nude, with multiple figures from classical mythology (Mars, Minerva, Mercury, Bacchus, Ariadne, Vulcan, the Three Graces), in positions where the foreshortening is usually abundant, in a great variety of postures and perspectives.In The Garden of Earthly Delights (1480–1490), The Last Judgment (1482), The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (1485) and The Haywain Triptych (1500–1502), the naked, human or subhuman form (demons, satyrs, mythological animals, monsters and fantastic creatures) proliferates in a paroxysm of lust that transcends any iconographic meaning and obeys only the feverish imagination of the artist.[108] Disciples of Rubens were Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens: the first, a great portraitist, evolved towards a more personal style, with a strong Italian influence, as in his Pietà on Prado (1618–1620) and the Saint Sebastian of the Alte Pinakothek in Munich, or in Diana and Endymion surprised by a satyr (1622–1627) and The Duke and Duchess of Buckingham as Venus and Adonis (1620).Jordaens was more faithful to his master—without reaching his height—as evidenced by the proliferation of nudes almost comparable to those of the Antwerp genius: The Satyr and the Peasant (undated), The Rape of Europa (1615–1616), Fertility (1623), Pan and Syrinx (1625), Apollo and Marsyas (1625), Prometheus Bound (1640), The Daughters of Cecrops Finding Erichthonius (1640), The Triumph of Bacchus (1645), The Rest of Diana (1645–1655), The Abundance of the Earth (1649), etc.An attempt to show perhaps sensual beauty was his Bathsheba at the Bath (1654), where he depicts her lover, Hendrickje Stoffels, which despite its rounded and generous forms, shown with honesty, manages to convey a feeling of nobility, not ideal, but sublime, while his meditative expression provides inner life to the carnal figure, and gives it a spiritual aura, reflecting the Christian concept of the body as a receptacle of the soul.In Spain, neoclassicism was practiced by several academic painters, such as Eusebio Valdeperas (Susanna and the Elders) and Dióscoro Teófilo Puebla (Las hijas del Cid, 1871), while neoclassical sculptors include José Álvarez Cubero (Ganymede, 1804; Apolino, 1810–1815; Nestor and Antilochus [or The Defense of Zaragoza], 1818), Juan Adán (Venus of the Alameda, 1795), Damià Campeny (Diana in the Bath, 1803; Dying Lucretia, 1804; Achilles removing the arrow from his heel, 1837), Antoni Solà (Meleagro, 1818), Sabino Medina (The nymph Eurydice bitten by an asp while fleeing from Eurystheus, 1865), Jeronimo Suñol (Hymenaeus, 1864), etc.[Note 11][141] A movement of profound renewal in all artistic genres, the Romantics paid special attention to the field of spirituality, imagination, fantasy, sentiment, dreamy evocation, love of nature, together with a darker element of irrationality, attraction to occultism, madness, dreams.Artist and writer, he illustrated his own literary works, or classics such as The Divine Comedy (1825–1827) or the Book of Job (1823–1826), with a personal style that reveals his inner world, full of dreams and emotions, with evanescent figures that seem to float in a space not subject to physical laws, generally in nocturnal environments, with cold and liquid lights, with a profusion of arabesques.[145] His disciples were: Antoine-Jean Gros, chronicler of the Napoleonic deeds, made in Bonaparte visiting the plague victims of Jaffa (1804) some nudes of intense dramatism, showing with crudeness the effects of the disease; and Théodore Chassériau, who tried to synthesize the line of Ingres with the colorfulness of Delacroix, although his work tends to academicism (Venus Anadyomene, 1838; Susanna and the Elders, 1839; Diana surprised by Actaeon, 1840; Andromeda chained to the rock by the Nereids, 1840; The Toilette of Esther, 1841; Sleeping Nymph, 1850; The Tepidarium, 1853).[156] One of the main representatives of academicism was William-Adolphe Bouguereau, who produced a large number of nude works, generally on mythological themes, with figures of great anatomical perfection, pale, with long hair and a gestural elegance not without sensuality (The Birth of Venus, 1879; Dawn, 1881; The Wave, 1896; The Oreads, 1902).Other artists were: François-Léon Benouville (The Wrath of Achilles, 1847), Auguste Clésinger (Woman Bitten by a Snake, 1847; Leda and the Swan, 1864), Paul Baudry (The Pearl and the Wave, 1862), Jules Joseph Lefebvre (The Truth, 1870; Mary Magdalene in the Cave, 1876), Henri Gervex (Rolla, 1878), Édouard Debat-Ponsan (Le massage au Hamam, 1883), Alexandre Jacques Chantron (Danae, 1891), Gaston Bussière (The Nereids, 1902), Guillaume Seignac (The Awakening of Psyche, 1904), etc.In Spain, Luis Ricardo Falero also had a special predilection for the female figure, with works where the fantastic component and orientalist taste stand out: Oriental Beauty (1877), The Vision of Faust (Witches going to their Sabbath) (1878), Enchantress (1878), The pose (1879), The Favorite (1880), Twin stars (1881), Lily Fairy (1888), The Butterfly (1893), etc.[170] The Swede Anders Zorn made unabashedly voluptuous and healthy nudes, usually in landscapes, with vibrant light effects on the skin, in bright brushstrokes of great color, as in In the Open Air (1888), The Bathers (1888), Women Bathing in the Sauna (1906), Girl Sunbathing (1913), Helga (1917), Studio Idyll (1918).[171] In Spain, the work of Joaquín Sorolla stood out, who interpreted impressionism in a personal way, with a loose technique and vigorous brushstroke, with a bright and sensitive coloring, where light is especially important, the luminous atmosphere that surrounds his scenes of Mediterranean themes, on beaches and seascapes where children play, society ladies stroll or fishermen are engaged in their tasks.His works are of a fantastic and ornamental style, with variegated compositions densely populated with all kinds of objects and plant elements, with a suggestive eroticism that reflects his fears and obsessions, with a prototype of an ambiguous woman, between innocence and perversity: Oedipus and the Sphinx (1864), Orpheus (1865), Jason and Medea (1865), Leda (1865–1875), The Chimera (1867), Prometheus (1868), The Rape of Europa (1869), The Sirens (1872), The Apparition (1874–1876), Salome (1876), Hercules and the Hydra of Lerna (1876), Galatea (1880), Jupiter and Semele (1894–1896).[175] Following in his footsteps were artists such as Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, who created large mural decorations in which he returned to linearity after the Impressionist experiments, with melancholic landscapes where the nude figure abounds, as in The Work (1863), Autumn (1865), Hope (1872), Young Girls by the Seashore (1879), The Sacred Grove, Beloved of the Arts and Muses (1884–1889), etc.[180] The German Franz von Stuck developed a decorative style close to modernism, although its subject matter is more symbolist, with an eroticism of torrid sensuality that reflects a concept of woman as the personification of perversity: Sin (1893), The Kiss of the Sphinx (1895), Air, Water, Fire (1913).[192] A precursor of expressionism was Edvard Munch: influenced in his beginnings by impressionism and symbolism, he soon drifted towards a personal style that would be a faithful reflection of his obsessive and tortured interior, with scenes of oppressive and enigmatic atmosphere—centered on sex, illness and death—characterized by the sinuosity of the composition and a strong and arbitrary coloring.Between 1903 and 1904 he executed several paintings of naked prostitutes where he recreates the depravity of their trade, reflecting in a horrendous way the materiality of the flesh, stripped of any ideal or moral component, with a sense of denunciation of the decadence of society coming from his neo-Catholic ideology, in an expressionist style of quick strokes and basic lines.Cubism (1907–1914) This movement was based on the deformation of reality through the destruction of the spatial perspective of Renaissance origin, organizing space according to a geometric grid, with simultaneous vision of objects, a range of cold and muted colors, and a new conception of the work of art, with the introduction of collage.[213] Although the Futurists were not particularly dedicated to the nude, it is worth remembering Umberto Boccioni and his Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), a modern version of the classical "heroic nudity", with which he sought "the abolition of the finite line and the closed statue", giving his figure a centrifugal force.In The electro-sexual sewing machine (1935) he shows a dreamlike delirium where the sexual component is combined with the mechanicity of the industrial era, through a naked woman's body lying face down, with a carnivorous plant devouring her feet and a stream of blood falling on her back through a funnel coming from a bull's head.Thus, for example, Julio Romero de Torres owed much of his fame to his academic nudes, but with a certain Leonardesque influence—in his beginnings he was tempted by pointillism, as in Vividoras del amor (1906), but he soon abandoned it—tinged with a dramatic and sensualist feeling typical of his Cordovan origin, as can be seen in The Gypsy Muse (1908), The Altarpiece of Love (1910), The Sin (1913), Venus of Poetry (1913), The Grace (1915), Rivalry (1925–1926), A Present to the Bullfighting Art (1929), Cante Jondo (1929), Trini's granddaughter (1929), etc.Pop-art (1955–1970) It emerged in Great Britain and the United States as a movement to reject abstract expressionism, encompassing a series of authors who returned to figuration, with a marked component of popular inspiration, taking images from the world of advertising, photography, comics and mass media.[141] One of the most successful artists in recent times has been Jenny Saville, who creates large works with figures seen from unusual perspectives, where the bodies resemble mountains of flesh that seem to fill the entire space, with a predilection for showing the genital areas, or imperfections and wounds of the skin, with bright, intense colors, arranged by spots, predominantly red and brown tones.[266] These images were mainly in vogue during the Edo period (1603–1867), usually in woodcut format, being practiced by some of the best artists of the time, such as Hishikawa Moronobu, Isoda Koryūsai, Kitagawa Utamaro, Keisai Eisen, Torii Kiyonaga, Suzuki Harunobu, Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Hiroshige.[267] After the opening of Japan to the West in the mid-19th century, Japanese art contributed to the development of the movement known as Japonisme, and several European artists collected shunga, including Aubrey Beardsley, Edgar Degas, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Gustav Klimt, Auguste Rodin, Vincent van Gogh and Pablo Picasso.

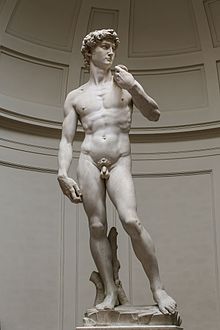

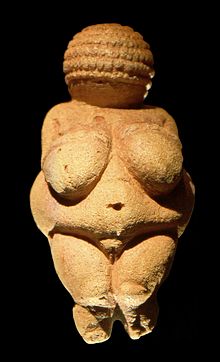

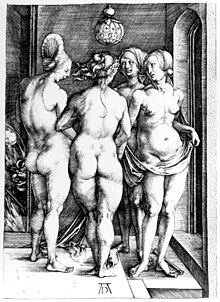

MichelangeloGalleria dell'Accademia, Florencehistory of artculturesartistic genrehuman bodyacademicworks of artaestheticsmoralityiconographicart historianshistory of Western arteroticismmythologyanatomicalAncient GreeceprehistoricVenus of WillendorfMiddle AgesbiblicalRenaissancehumanistanthropocentricImpressionismsemioticFeminismpatriarchalLucian FreudJenny SavilleKenneth ClarkJohn BergerWays of SeeingChantal JoffeAlice NeelNatural History Museum, ViennaPrehistoric artStone AgeUpper PaleolithicMesolithicNeolithic8000 BChuntedcave paintingshandicraftsprotohistoriccivilizationsPaleolithic artfertilityVenus figurinesAurignacianlimestonesteatiteWillendorfLespugueLausselphalliDorsetLevantinestick figuresEl CogulAlperaAncient artNear EastMesopotamiacontinentsBritish MuseumSumerianEgyptiananthropomorphiccosmologicalIshtarplanet VenusMother goddessSnake GoddessHeraklionMinoanArtemisDemeterpharaohSeated ScribeLouvreclimateThutmose IVSaqqarahTutankhamunHathorAssyrianLion Hunt of AshurbanipalChaldeanbronzePhoenicianMosaicAcropolisMoschophorosGreecenaturehuman beingharmonymimesisWestern artAncient Greek artMycenaeanhellenisticnaturalismAge of PericlesforeshorteningMarblekourosMetropolitan Museum of ArthumanisticOlympic GamesneoclassicismacademicismceramicArchaic periodAtticaPeloponneseKouros of Sounion600 BCCleobis and BitonRampin HorsemanKouros of TeneaKouros of AnafiEphebeKritios