Confederate war finance

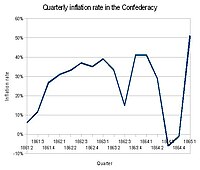

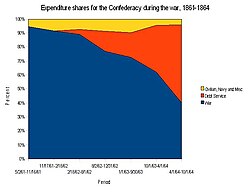

However, with the imposition of a voluntary self-embargo in 1861 (intended to "starve" Europe of cotton and force diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy), as well as the blockade of Southern ports, declared in April 1861 and enforced by the Union Navy, the revenue from taxes on international trade declined.Likewise, the appropriation of Union property in the South and the forced repudiation of debts owed by Southerners to Northerners failed to raise substantial revenue.The subsequent issuance of government debt and substantial printing of the Confederate dollars contributed to high inflation, which plagued the Confederacy until the end of the war.[3] The Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederate States, Christopher Memminger (in office 1861–1864), was keenly aware of the economic problems posed by inflation and loss of confidence.However, political considerations limited internal taxation ability, and as long as the voluntary embargo and the Union blockade remained in place, it was impossible to find adequate alternative sources of finance.[1] Taking account of difficulty of collection, the Confederate Congress passed a tax in kind in April 1863, which was set at one tenth of all agricultural product by state.[1] The financing of war expenditures by the means of currency issues (printing money) was by far the major avenue resorted to by the Confederate government.[3] Because of the amount of Southern debt held by foreigners, to ease currency convertibility, in 1863 the Confederate Congress decided to adopt the gold standard.[3] Cotton Bonds initially were very popular and in high demand among the British; William Ewart Gladstone, who at the time was the Chancellor of the Exchequer, was supposedly one of the buyers—his family fortune came from slavery in the West Indies.The Confederate government managed to honor the Cotton Bonds throughout the war, and in fact their price rose steeply until the fall of Atlanta to Sherman.However, in addition to the difficulties associated with the blockade, the self-imposed embargo on cotton meant that for all practical purposes the tax was completely ineffective as a fund raiser.This source, however, dried up over time as individuals and institutions in the South both ran down their personal holdings of bullion and became less willing to make donations as war-weariness set in.[1] Another potential source of finance could be found in the property and physical capital owned by Northerners in the South, and the debts owed by individuals in a parallel manner.

Confederate States of AmericaAmerican Civil Warfiscalmonetarytariffsimportsexportsembargocottondiplomatic recognition of the Confederacyblockade of Southern portsUnion Navyinternational tradebulliongovernment debtConfederate dollarsinflationSecretary of the Treasury of the Confederate StatesChristopher Memmingerdirect taxesstates' rightsRichmondtax burdenslavestax in kindConfederate Armymoney supplyaggregate price levelgrowth ratequantity theory of moneyvelocity of moneyreal outputequation of exchangedemand for moneycounterfeit billsSamuel C. UphamPhiladelphiaJefferson DavisUnited States Secret ServiceGreybackpublic financeMississippi RiverInterest Bearing NotesConfederate Congressgold standardCoinage Act of 1873primary deficitNew OrleansLondonNetherlandsWilliam Ewart GladstoneChancellor of the Exchequerthe fall of AtlantaShermanGeorge B. McClellanUS PresidentErlanger bankCotton is KingTariff of 1857war-wearinessphysical capitalEconomic history of the American Civil WarEconomy of the Confederate States of AmericaNiall FergusonJournal of Political EconomyOriginsTimeline leading to the WarBleeding KansasBorder statesCompromise of 1850John Brown's raid on Harpers FerryKansas-Nebraska ActLincoln–Douglas debatesMissouri CompromiseNullification crisisOrigins of the American Civil WarPanic of 1857Popular sovereigntySecessionSouth Carolina Declaration of SecessionPresident Lincoln's 75,000 volunteersSlaveryAfrican AmericansCornerstone SpeechCrittenden CompromiseDred Scott v. SandfordEmancipation ProclamationFire-EatersFugitive slave lawsPlantations in the American SouthPositive goodSlave PowerSlavery in the United StatesTreatment of slaves in the United StatesUncle Tom's CabinAbolitionismAbolitionism in the United StatesSusan B. AnthonyJames G. BirneyJohn BrownFrederick DouglassWilliam Lloyd GarrisonLane Debates on SlaveryElijah Parish LovejoyJ. Sella MartinLysander SpoonerGeorge Luther StearnsThaddeus StevensCharles SumnerCaningHarriet TubmanUnderground RailroadMarine CorpsRevenue Cutter ServiceConfederacyEasternWesternLower SeaboardTrans-MississippiPacific CoastUnion naval blockadecampaignsAnaconda PlanBlockade runnersNew MexicoJackson's Valley