Trent Affair

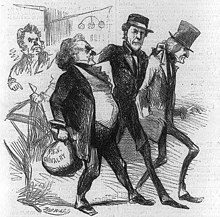

On November 8, 1861, USS San Jacinto, commanded by Union Captain Charles Wilkes, intercepted the British mail packet RMS Trent and removed, as contraband of war, two Confederate envoys: James Murray Mason from Virginia and John Slidell from Louisiana.[1] The Confederacy and its president, Jefferson Davis, believed from the beginning that European dependence on Southern cotton for its textile industry would lead to diplomatic recognition and intervention, in the form of mediation.[4] The Russian Minister in Washington, Eduard de Stoeckl, noted, "The Cabinet of London is watching attentively the internal dissensions of the Union and awaits the result with an impatience which it has difficulty in disguising."The first link in the chain of events occurred in February 1861, when the Confederacy created a three person European delegation consisting of William Lowndes Yancey, Pierre Rost, and Ambrose Dudley Mann.Their instructions from Confederate Secretary of State Robert Toombs were to explain to these governments the nature and purposes of the southern cause, to open diplomatic relations, and to "negotiate treaties of friendship, commerce, and navigation".Adams argued that Great Britain had recognized a state of belligerency "before they [the Confederacy] had ever showed their capacity to maintain any kind of warfare whatever, except within one of their own harbors under every possible advantage […] it considered them a maritime power before they had ever exhibited a single privateer upon the ocean."[15] Further problems developed over possible diplomatic recognition when, in mid-August, Seward became aware that Britain was secretly negotiating with the Confederacy in order to obtain its agreement to abide by the Declaration of Paris.The United States had failed to sign the treaty originally, but after the Union declared a blockade of the Confederacy, Seward ordered the U.S. ministers to Britain and France to reopen negotiations to restrict the Confederate use of privateers.U.S. Navy Secretary Gideon Welles reacted to the rumor that Mason and Slidell had escaped from Charleston by ordering Admiral Samuel F. DuPont to dispatch a fast warship to Britain to intercept Nashville.On October 15, the Union sidewheel steamer USS James Adger, under the command of John B. Marchand, began steaming towards Europe with orders to pursue Nashville to the English Channel if necessary.San Jacinto had cruised off the African coast for nearly a month before setting course westward with orders to join a U.S. Navy force preparing to attack Port Royal, South Carolina.Thurlow Weed's Albany Evening Journal suggested that, if Wilkes had "exercised an unwarranted discretion, our government will properly disavow the proceedings and grant England 'every satisfaction' consistent with honor and justice".[45] It did not take long for others to comment that the capture of Mason and Slidell very much resembled the search and impressment practices that the United States had always opposed since its founding and which had previously led to the War of 1812 with Britain."[51] Lincoln's annual message to Congress did not touch directly on the Trent affair but, relying on estimates from Secretary of War Simon Cameron that the U.S. could field a 3,000,000 man army, stated that he could "show the world, that while engaged in quelling disturbances at home we are able to protect ourselves from abroad".The London Chronicle's response was typical: Mr. Seward … is exerting himself to provoke a quarrel with all Europe, in that spirit of senseless egotism which induces the Americans, with their dwarf fleet and shapeless mass of incoherent squads which they call an army, to fancy themselves the equal of France by land and Great Britain by sea.These demonstrations were called in spite of the fact that the British ruling classes did everything in their power to make the workers believe that an alliance with the Confederacy would result in the breaking of the Northern blockade of Southern ports, which in turn, would mean the importation of greater quantities of cotton with consequent re-employment and prosperity.[66] The Times published its first report from the United States on December 4, and its correspondent, W. H. Russell, wrote of American reactions, "There is so much violence of spirit among the lower orders of the people and they are … so saturated with pride and vanity that any honorable concession … would prove fatal to its authors."[67] Times editor John T. Delane took a moderate stance and warned the people not to "regard the act in the worst light" and to question whether it made sense that the United States, despite British misgivings about Seward that went back to the earliest days of the Lincoln administration, would "force a quarrel upon the Powers of Europe".[70] Palmerston, who believed he had received a verbal agreement from Adams that British vessels would not be interfered with, reportedly began the emergency cabinet meeting by throwing his hat on the table and declaring, "I don't know whether you are going to stand this, but I'll be damned if I do.In an early December speech to his constituents, he condemned the British military preparations "before we have made a representation to the American Government, before we have heard a word from it in reply, [we] should be all up in arms, every sword leaping from its scabbard and every man looking about for his pistols and blunderbusses?"Referring to Jamaica, Milne reported conditions that included, "works badly contrived and worse executed—unserviceable guns—decayed gun cartridges—corroded shot—the absence of stores of all kinds and of ammunition, with dilapidated and damp powder magazines".This resistance by Parliament and the cabinet led historian Kenneth Bourne to conclude, "When, therefore the news of the Trent outrage arrived in England the British were still not properly prepared for the war which almost everyone agreed was inevitable if the Union did not back down.[102] Warren describes the Sedentary militia on their initial muster, before arms and equipment were served out to them: Untrained and undisciplined, they showed up in all manner of dress, with belts of basswood bark and sprigs of green balsam in their hats, carrying an assortment of flintlocks, shotguns, rifles, and scythes.[115] In 1864 Milne wrote that his own plan was: … to have secured our own bases, especially Bermuda and Halifax, raised the blockade of the Southern Ports by means of the squadron then at Mexico under the orders of Commodore Dunlop and that I had with me at Bermuda and then to have immediately blockaded as effectually as my means admitted the chief Northern Ports, and to have acted in Chesapeake Bay in co-operation with the Southern Forces …[116]Regarding possible joint operations with the Confederacy, Somerset wrote to Milne on December 15: …generally it will be well to avoid as much as possible any combined operations on a great scale (except as far as the fleet may be concerned), under any specious project such as for an attack on Washington or Baltimore; — experience proves almost invariably the great evils of combined operations by armies of different countries; and in this case, the advantage of the enemy of the defensive station will far more than compensate for the union of forces against it."[120] Military historian Russell Weigley concurs in Warren's analysis and adds: The Royal Navy retained the appearance of maritime supremacy principally because it existed in a naval vacuum, with no serious rivals except for halfhearted and sporadic challenges by the French.The Duchess of Argyll, a strong antislavery advocate in Great Britain, wrote Sumner that the capture of the envoys was "the maddest act that ever was done, and, unless the [United States] government intend to force us to war, utterly inconceivable.Adams wrote: The passions of the country are up and a collision is inevitable if the Government of the United States should, before the news reaches the other side, have assumed the position of Captain Wilkes in a manner to preclude the possibility of explanation.[136] On December 20, Salmon P. Chase's broker refused to sell some of the secretary's holdings of railway stock because they were almost worthless, and informed him that the business community "trust you will have allayed this excitement with England: one war at a time is enough".At the time of the Trent Affair, the North was not only refusing to acknowledge a state of war, but was still demanding that the British government withdraw its recognition of Confederate belligerency in the form of the Proclamation of Neutrality.Biographer James Randall argues that Lincoln's contribution was decisive, as it lay: in his restraint, his avoidance of any outward expression of truculence, his early softening of State Department's attitude toward Britain, his deference toward Seward and Sumner, his withholding of his own paper prepared for the occasion, his readiness to arbitrate, his golden silence in addressing Congress, his shrewdness in recognizing that war must be averted, and his clear perception that a point could be clinched for America's true position at the same time that full satisfaction was given to a friendly country.

Sailors of

San Jacinto

boarded

Trent

diplomatic incidentAmerican Civil WarUnited StatesUnited KingdomU.S. NavyConfederateRoyal Mail steamerPresident Abraham LincolnUSS San JacintoCharles Wilkesmail packetRMS TrentcontrabandJames Murray MasonVirginiaJohn SlidellLouisianadiplomatic recognitionAnglo-American relationsneutral rightsBritish North AmericaAbraham LincolnOregon boundary disputeJefferson DavisUnion blockadeWilliam H. SewardHenry John Temple, 3rd Viscount PalmerstonPig WarSecretary of StateLord PalmerstonNapoleon IIIBismarckPrussiaCentral AmericaEduard de StoecklCassius ClayCharles Francis AdamsLord LyonsWilliam Lowndes YanceyPierre Adolphe RostAmbrose Dudley MannJohn Russell, 1st Earl RussellPierre RostRobert Toombstheir own unsuccessful attemptLord RussellFort Sumterslave tradeQueen VictoriabelligerencyWikisourceCharles Francis Adams, Sr.Declaration of ParisprivateersRichard Bickerton Pemell Lyons, 1st Viscount LyonsRobert BunchCharleston, South CarolinaSouth CarolinaFrancis Wilkinson PickensNew Yorkdiplomatic pouchHenri MercierEdouard ThouvenelWilliam L. DaytonJohn BigelowFirst Battle of Bull RunJames MasonMexican WarR. M. T. HunterMarylandMissouriKentuckyItaly's struggles for independenceCSS NashvilleMexicoMatamorosGeorge TrenholmNassauBahamasSt. ThomasDanish West IndiesSpanish CubaGeorge Eustis Jr.Havanapaddle steamerCárdenas, CubaGideon WellesSamuel F. DuPontUSS James AdgerEnglish ChannelSouthamptonPalmerstonRoyal Navysteam frigatePort Royal, South CarolinaCSS SumterCienfuegosBahama ChannelD. M. Fairfaxgreat exploring missionUnion JackMr. EusticeHampton RoadsWashingtonBostonFort WarrenTheophilus ParsonsCaleb CushingAttorney GeneralSecretary of the NavyNew York TimesThurlow WeedWar of 1812James BuchananThomas EwingLewis CassRobert J. WalkerAlexander GaltSecretary of WarSimon CameronTreasury SecretarySalmon P. ChaseSenatorOrville BrowningClement L. VallandighamThe Times