Xiongnu

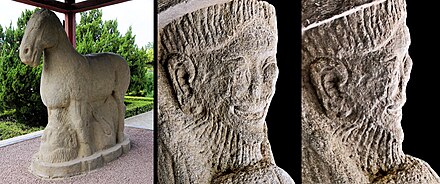

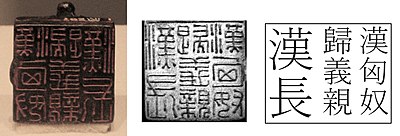

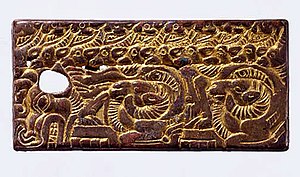

The identity of the ethnic core of Xiongnu has been a subject of varied hypotheses, because only a few words, mainly titles and personal names, were preserved in the Chinese sources.[34] The territories associated with the Xiongnu in central/east Mongolia were previously inhabited by the Slab Grave Culture (Ancient Northeast Asian origin), which persisted until the 3rd century BC.Pulleyblank argued that the Xiongnu were part of a Xirong group called Yiqu, who had lived in Shaanbei and had been influenced by China for centuries, before they were driven out by the Qin ty.This period of Chinese instability was a time of prosperity for the Xiongnu, who adopted many Han agriculture techniques such as slaves for heavy labor and lived in Han-style homes.In 200 BC, Modu besieged the first Han dynasty emperor Gaozu (Gao-Di) with his 320,000-strong army at Peteng Fortress in Baideng (present-day Datong, Shanxi).[72] After Gaozu (Gao-Di) agreed to all Modu's terms, such as ceding the northern provinces to the Xiongnu and paying annual taxes, he was allowed to leave the siege.Although Gaozu was able to return to his capital Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), Modu occasionally threatened the Han's northern frontier and finally in 198 BC, a peace treaty was settled.In the winter of 200 BC, following a Xiongnu siege of Taiyuan, Emperor Gaozu of Han personally led a military campaign against Modu Chanyu.The peace settlement eventually reached between the parties included a Han princess given in marriage to the chanyu (called heqin) (Chinese: 和親; lit.While the Han dynasty was making preparations for a military confrontation since the reign of Emperor Wen, the break did not come until 133 BC, following an abortive trap to ambush the chanyu at Mayi.[121] Ban Chao, Protector General (都護; Duhu) of the Han dynasty, embarked with an army of 70,000 soldiers in a campaign against the Xiongnu remnants who were harassing the trade route now known as the Silk Road.In 36 BC, a junior officer named Chen Tang, with the help of Gan Yanshou, protector-general of the Western Regions, assembled an expeditionary force that defeated him at the Battle of Zhizhi and sent his head as a trophy to Chang'an.According to the fifth-century Book of Wei, the remnants of Northern Chanyu's tribe settled as Yueban (悅般), near Kucha and subjugated the Wusun; while the rest fled across the Altai mountains towards Kangju in Transoxania.In addition to the poor living conditions of the frontiers, the Chinese court would also interfere in the Southern Xiongnu's politics and install chanyus loyal to the Han.The cohesion of the Southern Xiongnu began to erode, and while the other tribes appear to distant themselves from the ongoing Han civil war, the Xiuchuge stayed on the offensive."[132] Fang Xuanling's Book of Jin lists nineteen Xiongnu tribes that resettled within the Great Wall: Chuge (屠各), Xianzhi (鮮支), Koutou (寇頭), Wutan (烏譚), Chile (赤勒), Hanzhi (捍蛭), Heilang (黑狼), Chisha (赤沙), Yugang (鬱鞞), Weisuo (萎莎), Tutong (禿童), Bomie (勃蔑), Qiangqu (羌渠), Helai (賀賴), Zhongqin (鐘跂), Dalou (大樓), Yongqu (雍屈), Zhenshu (真樹) and Lijie (力羯).In Bing province, the Chuge identity held more weight than that of the Xiongnu among the Five Divisions, while those excluded from the group mingled with tribes from various ethnicities and were referred to as "hu" or other vague terms for the non-Chinese.Shi Le, the founder of the Later Zhao dynasty, was a descendant of the Xiongnu Qiangqu tribe, although by his time, he and his people had become a separate ethnic group known as the Jie.Unlike his predecessors, Liu Yao appealed more to his Xiongnu ancestry by honouring Modu Chanyu and distancing himself from the state's initial positioning of restoring the Han dynasty.Eventually, Liu Yao led his army to fight Later Zhao for control over Luoyang but was captured by Shi Le's forces in battle and executed in 329.He was assigned to guard Shuofang, but in 407, angered by Qin holding peace talks with the Northern Wei, he rebelled and founded a state known as the Helian Xia dynasty.[24] According to a study by Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong, published in 2020 in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences by Cambridge University Press, "The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic".[163] According to a study by Alexander Savelyev and Choongwon Jeong, published in 2020 in the journal Evolutionary Human Sciences by Cambridge University Press, "The predominant part of the Xiongnu population is likely to have spoken Turkic".[154] Other proponents of a Turkic language theory include E.H. Parker, Jean-Pierre Abel-Rémusat, Julius Klaproth, Gustaf John Ramstedt, Annemarie von Gabain,[154] and Charles Hucker.[229] In the 1920s, Pyotr Kozlov oversaw the excavation of royal tombs at the Noin-Ula burial site in northern Mongolia, dated to around the first century CE.Some of these embroidered portraits in the Noin-Ula kurgans also depict the Xiongnu with long braided hair with wide ribbons, which is seen to be identical with the Ashina clan hair-style.[233] Analysis of cranial remains from some sites attributed to the Xiongnu have revealed that they had dolichocephalic skulls with East Asian craniometrical features, setting them apart from neighboring populations in present-day Mongolia.They wrote that the bulk of the genetics research indicates that roughly 27% of Xiongnu maternal haplogroups were of West Eurasian origin, while the rest were East Asian.[256] A study published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology in October 2006 detected significant genetic continuity between the examined individuals at Egyin Gol and modern Mongolians.Historical evidence gives reason to believe that, from the 2nd century BC, proto-Mongol peoples (the Xiongnu, Xianbei, and Khitans) were familiar with Buddhism.

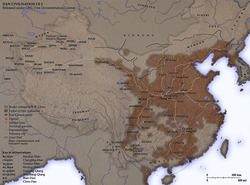

GRECOBACTRIANSPAR-THIASargatINDO-GREEKSKorgantasYUEZHISABEANSOrdoscultureDiancultureSELEUCIDEMPIREMAURYAEMPIREHANDYNASTYKhotanPTOLE-MIESMEROËSarmatiansSha-jingHan–Xiongnu WarsMongoliaKazakhstanKyrgyzstanSiberiaManchuriaXinjiangInner MongoliavariousShamanismTengrismBuddhismDemonym(s)TribalconfederationChanyuToumanLaoshangWudadihouAntiquitySlab Grave CultureDonghu peopleOrdos cultureHan dynastyXianbeiRouran KhaganateTochariansFirst Turkic KhaganateChineseStandard MandarinHanyu PinyinBopomofoGwoyeu RomatzyhWade–GilesTongyong PinyinYue: CantoneseYale RomanizationJyutpingSouthern MinTâi-lôOld ChineseHistory of MongoliaTimelineStatesRulersNobilityCulturePoliticsGeographyLanguageReligionPrehistoricAfanasievo cultureChemurchek cultureMunkhkhairkhan cultureSagsai cultureUlaanzuukh cultureDeer stones cultureSlab-grave cultureChandman culturePazyryk cultureXianbei stateGöktürksEasternSecond Turkic KhaganatesXueyantuoTang protectorateUyghur KhaganateLiao dynastyMongol khanatesKhamag MongolMongol EmpireYuan dynastyNorthern YuanOirat ConfederationDzungar KhanateQing dynastyNational RevolutionBogd KhaganateChinese occupationPeople's RevolutionSoviet intervention in Bogd KhanatePeople's RepublicDemocratic RevolutionModern Mongolianomadic peoplesChinese sourcesEurasian SteppeModu ChanyusteppesEast AsiaMongolian PlateauChinese dynastiescenturies-long conflictSixteen KingdomsFive BarbariansHan-ZhaoNorthern LiangHelian XiaarchaeogeneticscognateTurkicIranianMongolicUralicYeniseianMandarin ChineseEastern Han ChineseHūṇā