Aerodynamics

[2] Since then, the use of aerodynamics through mathematical analysis, empirical approximations, wind tunnel experimentation, and computer simulations has formed a rational basis for the development of heavier-than-air flight and a number of other technologies.Recent work in aerodynamics has focused on issues related to compressible flow, turbulence, and boundary layers and has become increasingly computational in nature.In 1871, Francis Herbert Wenham constructed the first wind tunnel, allowing precise measurements of aerodynamic forces.Drag theories were developed by Jean le Rond d'Alembert,[13] Gustav Kirchhoff,[14] and Lord Rayleigh.[15] In 1889, Charles Renard, a French aeronautical engineer, became the first person to reasonably predict the power needed for sustained flight.Building on these developments as well as research carried out in their own wind tunnel, the Wright brothers flew the first powered airplane on December 17, 1903.During the time of the first flights, Frederick W. Lanchester,[17] Martin Kutta, and Nikolai Zhukovsky independently created theories that connected circulation of a fluid flow to lift.Macquorn Rankine and Pierre Henri Hugoniot independently developed the theory for flow properties before and after a shock wave, while Jakob Ackeret led the initial work of calculating the lift and drag of supersonic airfoils.This rapid increase in drag led aerodynamicists and aviators to disagree on whether supersonic flight was achievable until the sound barrier was broken in 1947 using the Bell X-1 aircraft.By the time the sound barrier was broken, aerodynamicists' understanding of the subsonic and low supersonic flow had matured.These properties may be directly or indirectly measured in aerodynamics experiments or calculated starting with the equations for conservation of mass, momentum, and energy in air flows.Unlike liquids and solids, gases are composed of discrete molecules which occupy only a small fraction of the volume filled by the gas.On a molecular level, flow fields are made up of the collisions of many individual of gas molecules between themselves and with solid surfaces.However, in most aerodynamics applications, the discrete molecular nature of gases is ignored, and the flow field is assumed to behave as a continuum.The continuum assumption is less valid for extremely low-density flows, such as those encountered by vehicles at very high altitudes (e.g. 300,000 ft/90 km)[6] or satellites in Low Earth orbit.Evaluating the lift and drag on an airplane or the shock waves that form in front of the nose of a rocket are examples of external aerodynamics.For instance, internal aerodynamics encompasses the study of the airflow through a jet engine or through an air conditioning pipe.In air, compressibility effects are usually ignored when the Mach number in the flow does not exceed 0.3 (about 335 feet (102 m) per second or 228 miles (366 km) per hour at 60 °F (16 °C)).The presence of shock waves, along with the compressibility effects of high-flow velocity (see Reynolds number) fluids, is the central difference between the supersonic and subsonic aerodynamics regimes.The field of environmental aerodynamics describes ways in which atmospheric circulation and flight mechanics affect ecosystems.Sports in which aerodynamics are of crucial importance include soccer, table tennis, cricket, baseball, and golf, in which most players can control the trajectory of the ball using the "Magnus effect".

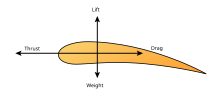

Potential flow

theory

Boundary layer flow

theory

Turbulent wake

analysis

Aerodynamic (disambiguation)wake turbulenceWallops IslandvortexAncient Greekairplanefluid dynamicsgas dynamicsaeronauticsaerodynamic dragOtto Lilienthalmathematicalwind tunnelcomputer simulationscompressible flowturbulenceboundary layerscomputationalHistory of aerodynamicsIcarusDaedaluscontinuumpressure gradientsAristotleArchimedesIsaac NewtonmathematicianDaniel BernoulliBernoulli's principleLeonhard EulerEuler equationsNavier–Stokes equationsWright brothersSir George CayleyweightthrustFrancis Herbert WenhamJean le Rond d'AlembertGustav KirchhoffLord RayleighCharles RenardairfoilsFrederick W. LanchesterMartin KuttaNikolai ZhukovskycirculationLudwig PrandtlMinistry of Aircraft Productioncompressibilityshock wavesaeroelastic flutterMach numberErnst MachsupersonicMacquorn RankinePierre Henri Hugoniotshock waveJakob AckeretTheodore von KármánHugh Latimer Drydentransoniccritical Mach numbersound barrierBell X-1Cold WarComputational fluid dynamicshypersonicmomentsflow velocitypressuredensitytemperaturemomentumviscositymoleculescontinuum assumptionmean free pathLow Earth orbitstatistical mechanicsKnudsen numberfluid continuumConservation of massConservation of momentumNewton's Second Lawsurface forcesfrictionalbody forcesvectorscalarConservation of energyheat transfercomputational techniquesLaplace's equationpotential flowBernoulli's equationideal gas lawequation of stateflow speedrocketjet engineair conditioningspeed of soundMach numbersinviscid flowsincompressible flowinviscidincompressibleirrotationaldifferential equationsstreamlinestagnation pointMach 1.2Concordestagnation pressureirreversibleReynolds numberBoundary layer flowTurbulent wakeBoundary layerlaminar flowAutomotive aerodynamicsvehicle designroad carstrucksdrag coefficientracing cars