Science communication

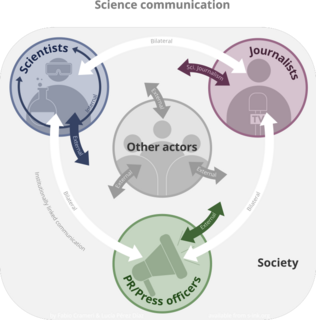

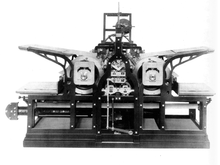

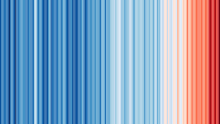

[30] An increasing number of scientists, especially younger scholars, are expressing interest in engaging the public through social media and in-person events, though they still perceive significant institutional barriers to doing so.[49] Hilgartner argued that what he called "the dominant view" of science popularization tends to imply a tight boundary around those who can articulate true, reliable knowledge.[11] Journalist Robert Krulwich likewise argued in 2008 that the stories scientists tell compete with the efforts of people such as Turkish creationist Adnan Oktar.[54] Krulwich explained that attractive, easy to read, and cheap creationist textbooks were sold by the thousands to schools in Turkey (despite their strong secular tradition) due to the efforts of Oktar.[54][12] Astrobiologist David Morrison has spoken of repeated disruption of his work by popular anti-scientific phenomena, having been called upon to assuage public fears of an impending cataclysm involving an unseen planetary object—first in 2008, and again in 2012 and 2017.[8] Closer collaboration could enrich the spectrum of science communication research and increase the existing methodological toolbox, including more longitudinal and experimental studies.[8] Evidence-based science communication would combine the best available evidence from systematic research, underpinned by established theory, as well as practitioners' acquired skills and expertise, reducing the double-disconnect between scholarship and practice.[62] Neither adequately take into account the other side's priorities, needs and possible solutions, Jensen and Gerber argued; bridging the gap and fostering closer collaboration could allow for mutual learning, enhancing the overall advancements of science communication as a young field.Science communication researchers and practitioners now often showcase their desire to listen to non-scientists as well as acknowledging an awareness of the fluid and complex nature of (post/late) modern social identities.While scientific study began to emerge as a popular discourse following the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, science was not widely funded or exposed to the public until the nineteenth century.[95] David Brewster, founder of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, believed in regulated publications in order to effectively communicate their discoveries, "so that scientific students may know where to begin their labours.Historian Aileen Fyfe noted that, as the nineteenth century experienced a set of social reforms that sought to improve the lives of those in the working classes, the availability of public knowledge was valuable for intellectual growth.As a result, scientific journals such as Nature or National Geographic possessed a large readership and received substantial funding by the end of the nineteenth century as the popularization of science continued.According to Karen Bultitude, a science communication lecturer at University College London, these can be broadly categorized into three groups: traditional journalism, live or face-to-face events, and online interaction.[105] Traditional journalism (for example, newspapers, magazines, television and radio) has the advantage of reaching large audiences; in the past, this is way most people regularly accessed information about science.[105] The traditional journalistic method of communication is one-way, so there can be no dialogue with the public, and science stories can often be reduced in scope so that there is a limited focus for a mainstream audience, who may not be able to comprehend the bigger picture from a scientific perspective.[108] Another disadvantage of traditional journalism is that, once a science story is taken up by mainstream media, the scientist(s) involved no longer has any direct control over how his or her work is communicated, which may lead to misunderstanding or misinformation.[112] Additionally, traditional media outlets have dramatically decreased the number of, or in some cases eliminated, science journalists and the amount of science-related content they publish.[105] Research has shown that members of the public seek out science information that is entertaining, but also helping citizens to critically participate in risk regulation and S&T governance.The third category is online interaction; for example, websites, blogs, wikis and podcasts can be used for science communication, as can other social media or forms of artificial intelligence like AI-Chatbots.Additionally, online communication of science can help boost scientists' reputation through increased citations, better circulation of articles, and establishing new collaborations.However, when engaging in communication about science online, scientists should consider not publicizing or reporting findings from their research until it has been peer-reviewed and published, as journals may not accept the work after it has been circulated under the "Ingelfinger rule".Either formally or in an informal context, an integration between artists and scientists could potentially raise awareness of the general public[125] about current topics in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM).[130] Alison Bert, editor in chief of Elsevier Connect, wrote a 2014 news article titled "How to use social media for science" that reported on a panel about social media at that year's AAAS meeting, in which panelists Maggie Koerth-Baker, Kim Cobb, and Danielle N. Lee noted some potential benefits and drawbacks to scientists of sharing their research on Twitter.[131] Koerth-Baker, for example, commented on the importance of keeping public and private personas on social media separate in order to maintain professionalism online.[131] Interviewed in 2014, Karen Peterson, director of Scientific Career Development at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center stressed the importance for scientists of using social networks such as Facebook and Twitter to establish an online presence.[133] Some scientists were hesitant to use social media outlets such as Twitter due to lack of knowledge of the platform, and inexperience with how to make meaningful posts.The 20th century saw groups founded on the basis they could position science in a broader cultural context and allow scientists to communicate their knowledge in a way that could reach and be understood by the general public.[48]: 5–7 One of the main assumptions drawn from the report was everybody should have some grasp of science and this should be introduced from a young age by teachers who are suitably qualified in the subject area.In the European Union, public views on public-funded research and the role of governmental institutions in funding scientific activities were being questioned as the budget allocated was increasing.

Scientific literatureScientific communicationScholarly communicationScience CommunicationCarsten Könnekersciencesocietypublic awareness of and interest in sciencepublic policyengaging with diverse communitiesoutreachpublicationscientific journalsscience journalismhealth communicationHistoryLiteratureMethodPhilosophyBranchesFormalNaturalPhysicalSocialAppliedIn societyCommunityEducationFundingPolicyPseudoscienceScientistOutlinemedical professionalsnature centerentertainmentpersuasionhumourstorytellingmetaphorssocial sciencescience educationcitizen sciencepublic engagement with sciencepublic understanding of sciencescientific literacypopular sciencescience fictionscience of happinessdemocratic societydecision makinganimals can feel painhuman activity influences climatescience of moralityscience and technology studiesBrian WynneMassimiano Bucchisocial epistemologytestimonyRandy Olsondenialismclimate change denialRobert KrulwichAdnan OktarcreationistDavid MorrisoncataclysmWalter LewinCarl SaganNeil deGrasse Tysonsensationalismclimate changeThe New York Timespersuasivestory tellingCaltechSir Isaac NewtonGalileoAlan AldaViola SpolinMatthew Nisbetopinion leadersNational Academy of SciencesNational Center for Science Educationevidence-based medicinemethodologicallongitudinal and experimental studiesThe Selfish GeneRichard DawkinspublicsEurobarometerframe analysisheuristicsTverskyKahnemanRepresentativenessAvailabilityAnchoring and adjustmentmarginalized groupsUniversity of Rhode IslandThomas Edisonlight bulbRenaissanceEnlightenmentpatronageRoyal SocietyPublic sciencesocial changeconveyor beltsteam locomotiveuniversitiesprofessionBritish Association for the Advancement of ScienceDavid Brewsterprofessionalizationpublic spheresteam-poweredprinting pressworking classesSociety for the Diffusion of Useful KnowledgeHenry BroughamperiodicalsPenny MagazineFredrich KoenigOxfordCambridge