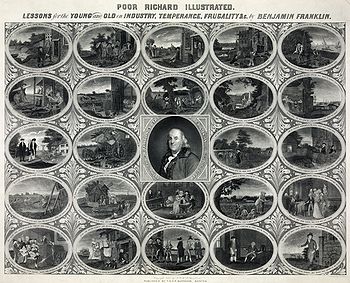

Poor Richard's Almanack

Almanacks were very popular books in colonial America, offering a mixture of seasonal weather forecasts, practical household hints, puzzles, and other amusements.[2] Poor Richard's Almanack was also popular for its extensive use of wordplay, and some of the witty phrases coined in the work survive in the contemporary American vernacular.Several of these sayings were borrowed from an earlier writer, Lord Halifax, many of whose aphorisms sprang from, "... [a] basic skepticism directed against the motives of men, manners, and the age.[9] Franklin borrowed the name "Richard Saunders" from the seventeenth-century author of Rider's British Merlin, a popular London almanac which continued to be published throughout the eighteenth century.By 1758, the original character was even more distant from the practical advice and proverbs of the almanac, which Franklin presented as coming from "Father Abraham," who in turn got his sayings from Poor Richard.Historian Howard Zinn offers, as an example, the adage "Let thy maidservant be faithful, strong, and homely" as indication of Franklin's belief in the legitimacy of controlling the sexual lives of servants for the economic benefit of their masters.[20] Sociologist Max Weber considered Poor Richard's Almanack and Franklin to reflect the "spirit of capitalism" in a form of "classical" purity."

Richard's Poor AlmanacalmanacBenjamin FranklinpseudonymThirteen Coloniesinventorpublisher and printerwordplayvernacularThe Pennsylvania Gazettecalendarweathersayingsastronomicalastrologicalmathematical exercisedemographicsaphorismsproverbsAmerican EnglishLord HalifaxThe Way to WealthRider's British MerlinJonathan SwiftIsaac BickerstaffJohn PartridgephilomathastrologerserialprotagonistsTitan LeedsNathaniel HawthorneHerman MelvilleJames Russell LowellBostonPhiladelphiaFranklin stovesocial normssocial moresThomas JeffersonJohn AdamsThomas PaineHoward ZinnJames FranklinLouis XVI of FranceJohn Paul JonesBonhomme Richardseveral US warshipsPennsylvania State ConstitutionCisalpine RepublicbroadsideclergySlovenePennsylvaniaNoah WebsterOld Farmer's AlmanacMax WeberThe Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalismfarmer's almanacsattack on Vice President Richard NixonCaracasThe Papers of Benjamin FranklinBibliography of Benjamin FranklinWilliam and Mary QuarterlyZinn, HowardA People's History of the United StatesIsaacson, WalterFranklin, BenjaminLibriVoxPresident of Pennsylvania (1785–1788)Ambassador to France (1779–1785)Second Continental Congress (1775–1776)Join, or Die. (1754 political cartoon)Albany Plan of UnionAlbany CongressHutchinson letters affairCommittee of Secret CorrespondenceCommittee of Five"...to be self-evident"Declaration of IndependenceModel TreatyFranco-American allianceTreaty of Amity and CommerceTreaty of AllianceStaten Island Peace Conference1776 Pennsylvania ConstitutionLibertas AmericanaTreaty of Paris, 1783Delegate, 1787 Constitutional ConventionPostmaster GeneralFounding FathersFranklin's electrostatic machineBifocalsLightning rodKite experimentPay it forwardAssociators111th Infantry RegimentJunto clubAmerican Philosophical SocietyLibrary Company of PhiladelphiaPennsylvania HospitalAcademy and College of PhiladelphiaUniversity of PennsylvaniaPhiladelphia ContributionshipUnion Fire CompanyEarly American currencyContinental Currency dollar coinFugio centStreet lightingPresident, Pennsylvania Abolition SocietyMaster, Les Neuf SœursGravesiteFounders OnlineSilence Dogood letters (1722)A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain (1725)The Busy-Body columns (1729)The Pennsylvania Gazette (1729–1790)Early American publishers and printersThe Drinker's Dictionary (1737)"Advice to a Friend on Choosing a Mistress" (1745)"The Speech of Polly Baker" (1747)Observations Concerning the Increase of Mankind, Peopling of Countries, etc. (1751)Experiments and Observations on Electricity (1751)The Way to Wealth (1758)Pennsylvania Chronicle (1767)