Pomerania in the High Middle Ages

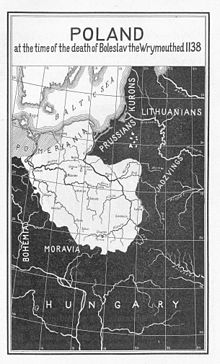

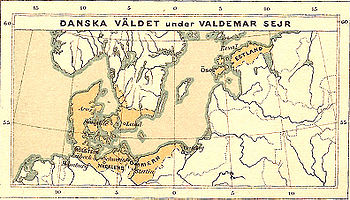

The early 12th century Obodrite, Polish, Saxon, and Danish conquests resulted in vassalage and Christianization of the formerly pagan and independent Pomeranian tribes.[1] The dukes of Pomerania expanded their realm into Circipania and Uckermark to the southwest, and competed with the Kingdom of Poland and the Margraviate of Brandenburg for territory and formal overlordship over their duchies.[7] The Rani Svantevit priests were forced to negotiate,[9] and the island was spared only in return for an immense sum which had to be collected from the continental Slavs further east.Regrouping after Henry's death (1127), the Rani again assaulted and this time destroyed Liubice in 1128,[9][10] ending Obodrite influence in the Pomeranian territories.[14] The conquest resulted in a high death toll and devastation of vast areas of Pomerania, and the Pomeranian dukes became vassals of Boleslaw III of Poland.The areas stretching from Kołobrzeg to Szczecin were ruled by Ratibor's brother Wartislaw I and his descendants (House of Pomerania, also called Griffins, of which he was the first ascertained ancestor) until the 1630s.[25][28][32] Otto then was titled apostolus gentis Pomeranorum, made a saint by pope Clement III in 1189, and was worshiped in Pomerania even after the Protestant Reformation.[34][35] Fate of the pagan priesthood The priests of the numerous gods worshipped before the conversion were one of the most powerful class in the early medieval society.On the other hand, Otto of Bamberg's mission was a far larger threat to the established pagan tradition, and eventually it succeeded in Christianization of the region.[35] On Otto of Bamberg's behalf, a diocese was founded with the see in Wollin (Julin, Jumne, Vineta),[25] a major Slavic and Viking town in the Oder estituary.[34] After ongoing Danish raids, Wollin was destroyed, and the see of the diocese was shifted across the Dziwna to Kamień Pomorski's St John's church in 1176.After the successful conversion of the nobility, monasteries were set up on vast areas granted by local dukes both to further implement Christian faith and to develop the land.His brother Ratibor I, duke in the Lands of Schlawe and Stolp, ruled in place of Wartislaw's sons, Bogislaw I and Casimir I until his death in about 1155.[44] After Wartislaw's Lutician conquests, his duchy lay between the Bay of Greifswald to the north, Circipania, including Güstrow, to the west, Kolberg/Kołobrzeg in the east, and possibly as far as the Havel and Spree rivers in the south.[45] After the conquests, Wartislaw's realm stretched from the Bay of Greifswald in the North and Circipania with Güstrow in the West to the Havel and possibly also the Spree rivers in the South and the Kolobrzeg area in the east.The Polish duke Boleslaw III, during his Pomeranian campaign launched an expedition into the Müritz area in 1120/21,[49] before he turned back to subdue Wartislaw.[49][clarification needed] Also, the territories were invaded by Danish forces multiple times, who, coming from the Baltic Sea, used the rivers Peene and Uecker to advance to a line Demmin–Pasewalk.[50] During Wartislaw I's rule society was composed of the Pomeranian freeman and the slaves, who consisted mostly of Wendish, German or Danish war captives.[nb 1] The population of Pomerania was relatively wealthy in comparison to her neighbors, owing to abundant land, inter-regional trade and piracy.[54][56] At that time, the duchy was also referred to as Slavinia (German: Slawien) (yet this was a term applied to several Wendish areas such as Mecklenburg and the Principality of Rügen).On emperor Barbarossa's initiative, Bogislaw was to take the Principality of Rügen from the Danes, whose king Canut VI had refused him the oath of fealty.[36] Beginning in the 12th century, on the initiative of monasteries,[60] as well as the local nobility, German settlers began migrating to Pomerania in a process later termed the Ostsiedlung.The local nobles and rulers encouraged the settlement in order to strengthen and consolidate their position and to develop and intensify land use, while the settlers were attracted by the privileges that were granted to them.In addition, the Danes withdrew from most of Pomerania in 1227, leaving the duchy vulnerable to their expansive neighbors, especially Mecklenburg, Brandenburg, and Henry I of Silesia.[65] Before the Ostsiedlung, urban settlements of the emporia[clarification needed] and gard[nb 1] types existed, for example the city of Szczecin (Stettin) which counted between 5,000 and 9,000 inhabitants,[66][67] and other locations like Demmin, Wolgast, Usedom, Wollin/Wolin, Kolberg/Kołobrzeg, Pyritz/Pyrzyce and Stargard, though many of the coastal ones declined during the 12th century warfare.[68] Previous theories that urban development was "in its entirety" brought to areas such as Pomerania, Mecklenburg or Poland by Germans are now discarded, and studies show that these areas had already growing urban centres in process similar to Western Europe[69] These population centres were usually centered on a gard, which was a fortified castle which housed the castellan as well as his staff and the ducal craftsmen.According to Piskorski this portion usually included "markets, taverns, butcher shops, mints, which also exchanged coins, toll stations, abbeys, churches and the houses of nobles".[70] Important changes connected to Ostsiedlung included Between 1234 and 1299, 34 towns[80] were founded[82] in the Pomeranian duchy, this number increased to 58 in the late Middle Ages.[86] In western Pomerania, including Rugia, the process of Ostsiedlung differed from how it took place in other parts of Eastern Europe in that a high proportion of the settlers was composed of Scandinavians, especially Danes, and migrants from Scania.Until 1250, Barnim I, Duke of Pomerania had recovered most of the previous Pomeranian territory[97] and sought to secure them with the settlement of Germans, while Zantoch burgh was held by Przemysł II of Greater Poland.

History of PomeraniaEarly historyEarly Middle AgesLate Middle AgesEarly modern period1806–19331933–19451945–presentObodritePolishDanishvassalageChristianizationPomeranianPrincipality of RügenDuchy of PomeraniaHouse of PomeraniaLands of Schlawe and StolpPomereliaSamboridesdukes of PomeraniaCircipaniaUckermarkKingdom of PolandMargraviate of BrandenburgLow GermanOstsiedlungduring the Early Middle AgesSlavicLuticianGerman PomeranianKashubiansSlavic Pomeraniansconversion of PomeraniaChristianityAbsalonOtto von BambergA Pomeranian dioceseCamminBattle of SchmilauHelmold of BosauLuticiansPomeraniansLiubiceLübeckWendishSvantevitWartislaw I, Duke of PomeraniaBolesław III WrymouthNotećParsętaLevantDenmarkÖlandBiałogardŚwiecieLubieszewoPomerania properSłupskSławnoRatibor IKołobrzegWartislaw IBoleslaw III of PolandSpanishBernardbishop of LebusOtto of BambergBambergBavariaPyritzStolpeWartislawWestern PomeranianGützkowWolgastKamień PomorskiUsedomClement IIIProtestant ReformationGnieznoAdalbert of PomeraniaChristianization of PomeraniacrucifiedWollinRoman Catholic Diocese of KammindioceseVinetaBishopPope Innocent IIDiocese of BambergDiocese of MagdeburgDiocese of GnieznoHoly SeeTribseesŁeba RiverNeumarkRatibor I, Duke of PomeraniaDziwnaKoszalinKuyavianDiocese of WłocławekWendish CrusadeNorthern CrusadesDemminStettinAdalbertImperial DietHavelbergRatiborStolpe AbbeyPartitions of the Duchy of PomeraniaBogislaw ICasimir ITollenseDievenowUeckerKolbergSzczecinLuticiOder LagoonPrincipality of GützkowBay of GreifswaldGüstrowNordmarkmargrave