Macedonia (ancient kingdom)

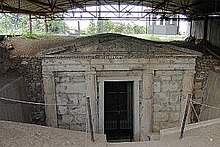

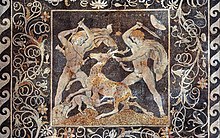

Home to the ancient Macedonians, the earliest kingdom was centered on the northeastern part of the Greek peninsula,[8] and bordered by Epirus to the southwest, Illyria to the northwest, Paeonia to the north, Thrace to the east and Thessaly to the south.[14] The assertion that the Argeads descended from Temenus was accepted by the Hellanodikai authorities of the Ancient Olympic Games, permitting Alexander I of Macedon (r. 498–454 BC) to enter the competitions owing to his perceived Greek heritage.[27] His successor Perdiccas II (r. 454–413 BC) led the Macedonians to war in four separate conflicts against Athens, leader of the Delian League, while incursions by the Thracian ruler Sitalces of the Odrysian kingdom threatened Macedonia's territorial integrity in the northeast.[59] Confusing accounts in ancient sources have led modern scholars to debate how much Philip II's royal predecessors may have contributed to these reforms and the extent to which his ideas were influenced by his adolescent years of captivity in Thebes as a political hostage during the Theban hegemony, especially after meeting with the general Epaminondas.[76] Meanwhile, Phocis and Thermopylae were captured by Macedonian forces, the Delphic temple robbers were executed, and Philip II was awarded the two Phocian seats on the Amphictyonic Council and the position of master of ceremonies over the Pythian Games.Despite the Kingdom of Macedonia's official exclusion from the league, in 337 BC, Philip II was elected as the leader (hegemon) of its council (synedrion) and the commander-in-chief (strategos autokrator) of a forthcoming campaign to invade the Achaemenid Empire.[106] While utilizing effective propaganda such as the cutting of the Gordian Knot, he also attempted to portray himself as a living god and son of Zeus following his visit to the oracle at Siwah in the Libyan Desert (in modern-day Egypt) in 331 BC.[107] His attempt in 327 BC to have his men prostrate before him in Bactra in an act of proskynesis borrowed from the Persian kings was rejected as religious blasphemy by his Macedonian and Greek subjects after his court historian Callisthenes refused to perform this ritual.Before Antipater died in 319 BC, he named the staunch Argead loyalist Polyperchon as his successor, passing over his own son Cassander and ignoring the right of the king to choose a new regent (since Philip III was considered mentally unstable), in effect bypassing the council of the army as well.[125] Forming an alliance with Ptolemy, Antigonus, and Lysimachus, Cassander had his officer Nicanor capture the Munichia fortress of Athens' port town Piraeus in defiance of Polyperchon's decree that Greek cities should be free of Macedonian garrisons, sparking the Second War of the Diadochi (319–315 BC).[9] Antigonus promptly allied with Polyperchon, now based in Corinth, and issued an ultimatum of his own to Cassander, charging him with murder for executing Olympias and demanding that he hand over the royal family, King Alexander IV and the queen mother Roxana.[172] Rome responded by sending ten heavy quinqueremes from Roman Sicily to patrol the Illyrian coasts, causing Philip V to reverse course and order his fleet to retreat, averting open conflict for the time being.[181] Although Rome's envoys played a critical role in convincing Athens to join the anti-Macedonian alliance with Pergamon and Rhodes in 200 BC, the comitia centuriata (people's assembly) rejected the Roman Senate's proposal for a declaration of war on Macedonia.[185] When the comitia centuriata finally voted in approval of the Roman Senate's declaration of war in 200 BC and handed their ultimatum to Philip V, demanding that a tribunal assess the damages owed to Rhodes and Pergamon, the Macedonian king rejected it.[186] The Macedonians successfully defended their territory for roughly two years,[187] but the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus managed to expel Philip V from Macedonia in 198 BC, forcing his men to take refuge in Thessaly.[199] Although Eumenes II attempted to undermine these diplomatic relationships, Perseus fostered an alliance with the Boeotian League, extended his authority into Illyria and Thrace, and in 174 BC, won the role of managing the Temple of Apollo at Delphi as a member of the Amphictyonic Council.[note 15] From at least the reign of Philip II, the king was assisted by the royal pages (basilikoi paides), bodyguards (somatophylakes), companions (hetairoi), friends (philoi), an assembly that included members of the military, and (during the Hellenistic period) magistrates.[216] Alexander imitated various aspects of his father's reign, such as granting land and gifts to loyal aristocratic followers,[216] but lost some core support among them for adopting some of the trappings of an Eastern, Persian monarch, a "lord and master" as Carol J.[219] They were split into two categories: the agema of the hypaspistai, a type of ancient special forces usually numbering in the hundreds, and a smaller group of men handpicked by the king either for their individual merits or to honor the noble families to which they belonged.[224] The assembly was apparently given the right to judge cases of high treason and assign punishments for them, such as when Alexander the Great acted as prosecutor in the trial and conviction of three alleged conspirators in his father's assassination plot (while many others were acquitted).[243] Nicholas Viktor Sekunda states that at the beginning of Philip II's reign in 359 BC, the Macedonian army consisted of 10,000 infantry and 600 cavalry,[244] yet Malcolm Errington cautions that these figures cited by ancient authors should be treated with some skepticism.[259] Thanks to contemporary inscriptions from Amphipolis and Greia dated 218 and 181 BC, respectively, historians have been able to partially piece together the organization of the Antigonid army under Philip V.[note 30] From at least the time of Antigonus III Doson, the most elite Antigonid-period infantry were the peltasts, lighter and more maneuverable soldiers wielding peltai javelins, swords, and a smaller bronze shield than Macedonian phalanx pikemen, although they sometimes served in that capacity.[263] Following its adoption as the court language of Philip II of Macedon's regime, authors of ancient Macedonia wrote their works in Koine Greek, the lingua franca of late Classical and Hellenistic Greece.[276] Young Macedonian men were typically expected to engage in hunting and martial combat as a by-product of their transhumance lifestyle of herding livestock such as goats and sheep, while horse breeding and raising cattle were other common pursuits.[290] Mosaics with mythological themes include scenes of Dionysus riding a panther and Helen of Troy being abducted by Theseus, the latter of which employs illusionist qualities and realistic shading similar to Macedonian paintings.[290] Common themes of Macedonian paintings and mosaics include warfare, hunting, and aggressive masculine sexuality (i.e. abduction of women for rape or marriage); these subjects are at times combined within a single work and perhaps indicate a metaphorical connection.[note 41] The philosopher Aristotle, who studied at the Platonic Academy of Athens and established the Aristotelian school of thought, moved to Macedonia, and is said to have tutored the young Alexander the Great, as well as serving as an esteemed diplomat for Philip II.However, Alexander I produced proof of an Argead royal genealogy showing ancient Argive Temenid lineage, a move that ultimately convinced the Olympic Hellanodikai authorities of his Greek descent and ability to compete.[346] Macedonians then migrated to Egypt and parts of Asia, but the intensive colonization of foreign lands sapped the available manpower in Macedonia proper, weakening the kingdom in its fight with other Hellenistic powers and contributing to its downfall and conquest by the Romans.[347] However, the diffusion of Greek culture and language cemented by Alexander's conquests in West Asia and North Africa served as a "precondition" for the later Roman expansion into these territories and entire basis for the Byzantine Empire, according to Errington.

Kingdom of

Ptolemy I Soter

Kingdom of

Cassander

Kingdom of

Lysimachus

Kingdom of

Seleucus I Nicator

Other

Macedon (disambiguation)Macedonia Vergina SunAncient MacedonianKoine GreekGreek polytheismHellenistic religionDemonym(s)MacedonianHereditary monarchyBasileusPhilip IIAlexander the GreatPerseusAndriscusSynedrionClassical AntiquityfoundationCaranusPerdiccas IVassalPersiaIncorporated into the Persian EmpireRise of MacedonFounding of the Hellenic LeagueConquest of PersiaPartition of BabylonWars of the DiadochiBattle of PydnaTetradrachmGreek Dark AgesAchaemenid MacedoniaLeague of CorinthAchaemenid EmpirePauravasLysimachian EmpireSeleucid EmpirePtolemaic KingdomAttalid kingdomMacedonia provinceancientkingdomArchaicClassical GreeceHellenistic Greecekingdom was foundedArgead dynastyAntipatridAntigonidancient MacedoniansGreek peninsulaEpirusIllyriaPaeoniaThraceThessalycity-statesAthensSpartaThebesbriefly subordinateAchaemenid PersiaPhilip IIsubduedmainland GreeceThracianOdrysian kingdomphalanxessarissaBattle of Chaeroneafederation of Greek statesdestroyed Thebescampaign of conquestoverthrewIndus RiverHellenisticAncient Greek civilizationGreek artsliteraturephilosophyengineeringscienceAristotlewhose writingsWestern philosophyAlexander's deathPtolemaic EgyptAmphipolisThessalonicaCassanderThessalonike of MacedonMacedonian Warsthe riseMediterraneanThird Macedonian Warthe Macedonian monarchy was abolishedclient statesFourth Macedonian WarRoman provinceabsolute powerstate resourcescurrencytheir armiesdiadochisuccessor statesimperial culthigh priestsa few municipalitiesMacedonian commonwealthdemocratic governmentspopular assembliesMakedon (mythology)Macedonia (terminology)ethnonymancient GreekμακεδνόςDoriansHerodotuscognateRobert S. P. BeekesPre-Greek substrateIndo-EuropeanHistory of Macedonia (ancient kingdom)VerginaUNESCO World Heritage SiteClassical