Relief

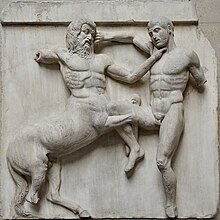

On the other hand, a relief saves forming the rear of a subject, and is less fragile and more securely fixed than a sculpture in the round, especially one of a standing figure where the ankles are a potential weak point, particularly in stone.In other materials such as metal, clay, plaster stucco, ceramics or papier-mâché the form can be simply added to or raised up from the background.The definition of these terms is somewhat variable, and many works combine areas in more than one of them, rarely sliding between them in a single figure; accordingly some writers prefer to avoid all distinctions.Relief is more suitable for depicting complicated subjects with many figures and very active poses, such as battles, than free-standing "sculpture in the round".The Ishtar Gate of Babylon, now in Berlin, has low reliefs of large animals formed from moulded bricks, glazed in colour.Plaster, which made the technique far easier, was widely used in Egypt and the Near East from antiquity into Islamic times (latterly for architectural decoration, as at the Alhambra), Rome, and Europe from at least the Renaissance, as well as probably elsewhere.However, it needs very good conditions to survive long in unmaintained buildings – Roman decorative plasterwork is mainly known from Pompeii and other sites buried by ash from Mount Vesuvius.Low relief was relatively rare in Western medieval art, but may be found, for example in wooden figures or scenes on the insides of the folding wings of multi-panel altarpieces.Since the Renaissance plaster has been very widely used for indoor ornamental work such as cornices and ceilings, but in the 16th century it was used for large figures (many also using high relief) at the Chateau of Fontainebleau, which were imitated more crudely elsewhere, for example in the Elizabethan Hardwick Hall.It is often used for the background areas of compositions with the main elements in low-relief, but its use over a whole (usually rather small) piece was effectively invented and perfected by the Italian Renaissance sculptor Donatello.The typical traditional definition is that only up to half of the subject projects, and no elements are undercut or fully disengaged from the background field.The metopes of the Parthenon have largely lost their fully rounded elements, except for heads, showing the advantages of relief in terms of durability.Famous examples of Indian high reliefs can be found at the Khajuraho temples, with voluptuous, twisting figures that often illustrate the erotic Kamasutra positions.The technique is most successful with strong sunlight to emphasise the outlines and forms by shadow, as no attempt was made to soften the edge of the sunk area, leaving a face at a right-angle to the surface all around it.Though essentially very similar to Egyptian sunk relief, but with a background space at the lower level around the figure, the term would not normally be used of such works.Sunk relief technique is not to be confused with "counter-relief" or intaglio as seen on engraved gem seals – where an image is fully modeled in a "negative" manner.

Relief (emotion)Relief (disambiguation)Hindu goddessesVaishnaviVarahiIndraniChamundaNational Museum of Indiasculpturalrelief carvingstuccopapier-mâchébronzecastingAncient Egyptintagliomonumental sculptureFrieze of ParnassusAlbert MemorialarabesquesIslamic artAra PacisRock reliefsAncient Near EastParthenon FriezesestertiusItalianart of Ancient EgyptAssyrian palace reliefsancient Near EasternSimurrumIshtar GateBabylonNear EastAlhambraPompeiiMount Vesuviusmedieval artaltarpiecesTempio MalatestianoRiminiLeon Battista AlbertiAgostino di DuccioornamentalcornicesChateau of FontainebleauHardwick HallstiacciatoDonatellostone carvingmetal castingArt DecoEric GillAhkenatenNefertitibas-reliefPersepolisZoroastrianequinoxAssyrian low reliefLion Hunt of AshurbanipalNinevehAtroposrilievo stiacciatoa tombBanteay SreiCambodiaRavanaKailasaBuddhist artSoutheast AsiaAjanta CavesEllora CavesBorobudurCentral JavaIndonesiaJataka talesBuddhaRamayanaPrambananAngkorSamudra manthanAngkor WatapsarasAngkor ThomKhmer EmpiremetopeParthenon MarblescentaurAncient Greek sculpturemetopes of the ParthenonKhajurahoMonument to the Independence of BrazilSão PauloPedro AméricoIndependence or DeathHellenisticsarcophaguschiselsLudovisi Battle sarcophagustriumphal columnssarcophagiAncient Roman sculpturefunerary artNeoclassicalpedimentsKamasutraLokapaladevatasGeorgiaAkhenatenAmarna periodhieroglyphscartouchesom mani padme hummani stonesTibetan Buddhismengraved gemdiptychLife of Christdecorative artsceramicsmetalworkplaquettesrepousséhardstone carvings