Helladic chronology

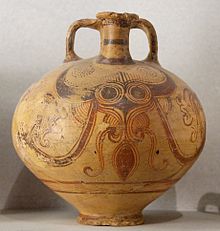

The systems derive primarily from changes in the style of pottery, which is a benchmark for relative dating of associated artifacts such as tools and weapons.On the basis of style and technique, Evans divided his Cretan Bronze Age pottery finds into three main periods which he called Early, Middle and Late Minoan.Evans' system has stood the test of time remarkably well but his labels do not provide firm dates because change is never constant and some styles were retained in use much longer than others.Helladic society and culture have antecedents in Neolithic Greece when most settlements were small villages which subsisted by means of agriculture, farming and hunting.Unlike the Egyptian and Mesopotamian civilisations, the Aegean peoples were illiterate through the third millennium and so, in the absence of useful written artifacts, any attempt at chronology must be based on the dating of material objects.Important EH sites are clustered on the Aegean shores of the mainland in Boeotia and Argolid (Manika, Lerna, Pefkakia, Thebes, Tiryns) or coastal islands such as Aegina (Kolonna) and Euboea (Lefkandi) and are marked by pottery showing influences from western Anatolia and the introduction of the fast-spinning version of the potter's wheel.[13] The nature of the destruction of EHII sites was at first attributed to an invasion of Greeks and/or Indo-Europeans during the Early Helladic III or Tiryns culture period c.2200–2000 BC (or EHIII);[14] however, this is no longer maintained given the lack of uniformity in the destruction of EHII sites and the presence of EHII–EHIII/MH continuity in settlements such as Lithares, Phlius, Manika, etc.[15] Furthermore, the presence of "new/intrusive" cultural elements such as apsidal houses, terracotta anchors, shaft-hole hammer-axes, ritual tumuli, and intramural burials precede the EHIII period in Greece and are in actuality attributed to indigenous developments (i.e. terracotta anchors from Boeotia; ritual tumuli from Ayia Sophia in Neolithic Thessaly), as well as continuous contacts during the EHII–MH period between mainland Greece and various areas such as western Asia Minor, the Cyclades, Albania, and Dalmatia.[20] In general, painted pottery decors are rectilinear and abstract until Middle Helladic III, when Cycladic and Minoan influences inspired a variety of curvilinear and even representational motifs.Cist graves are deep and rectangular with a tumulus, or mound of earth, placed over top and came about during the beginning of the Middle Helladic period.[23] A larger, free standing house has been identified as a possible home to a chief or leader of the community, and features a separate a storage facility as well as a courtyard with a hearth.Agriculture included the growing of crops like wheat (which would be ground into flour for baking), barley, flax, peas, chickpeas, lentils, and beans.The textile industry was prominent where they spin thread to be woven into fabrics on a loom, and the clothes they made were both fastened and often decorated with pins.More often than women, men also had higher level of lesions caused by infectious diseases, meaning they had greater exposure to foreign pathogens through direct contact with outside groups and people.The table below provides the approximate dates of the Late Helladic phases (LH) on the Greek mainland, based on Knodell (2021) and Manning (2010):[25] The LHI pottery is known from the fill of the Shaft Graves of Lerna and the settlements of Voroulia and Nichoria (Messenia), Ayios Stephanos, (Laconia) and Korakou.The uniform and widely spread LHIIIA:1 pottery was defined by the material from the Ramp house at Mycenae, the palace at Thebes (now dated to LHIIIA:2 or LHIIIB by most researchers) and Triada at Rhodes.LHIIIB:2 assemblages are sparse, as painted pottery is rare in tombs and many settlements of this period ended by destruction, leaving few complete pots behind.Pulak's proposed LHIIIA/B boundary would make LHIIIB contemporary in Anatolia with the resurgent Hittites following Mursili's eclipse; in Egypt with the 19th Dynasty, also known as the Ramessides; and in northern Mesopotamia with Assyria's ascendancy over Mitanni.In the 1960s, the excavations of the citadel at Mycenae and of Lefkandi in Euboea yielded stratified material revealing significant regional variation in LHIIIC, especially in the later phases.During the Helladic period, a number of major advances were developed including fortified urban settlements with monumental buildings such as corridor houses, which may prove the existence of complex societies organized by an elite or at least achieving corporate, proto-city state form.[32] The structure dates to the Early Helladic II period (2500–2300 BC) and is sometimes interpreted as the dwelling of an elite member of the community, a proto-palace, or an administrative center.[35] Although such roofs were also found in the Early Helladic site of Akovitika,[36] and later in the Mycenaean towns of Gla and Midea,[37] they only became common in Greek architecture in the 7th century BC.[32] Other fortified settlements include Tiryns, which covered an area of 5.9 hectares sustaining 1,180–1,770 people,[29] and had a large tiled two-storeyed "round house" (Rundbau) with a diameter of 28 m on the upper citadel.

Bronze AgeThebesTirynsMycenaeNeolithic GreeceGreek Dark AgesHistory of GreecePelasgiansGreek Bronze AgeCycladicMinoanMyceneanAncient GreeceArchaic GreeceClassical GreeceHellenistic GreeceRoman GreeceMedieval GreeceByzantine GreeceFrankish and Latin statesEarly modern GreeceVenetian CreteVenetian Ionian IslandsOttoman GreeceModern GreeceSeptinsular RepublicWar of IndependenceFirst Hellenic RepublicKingdom of GreeceNational SchismSecond Hellenic Republic4th of August RegimeAxis occupationCollaborationist regimeFree GreeceCivil WarMilitary JuntaThird Hellenic RepublicAgricultureAlphabetConstitutionEconomyEthnonymsLanguageMilitaryarchaeologyart historyMinoan chronologyArthur EvansMinoan civilizationmainland GreeceCycladic chronologyAegean islandsAegean artAegean civilizationpotterymetallurgyarchitecturefortificationsMycenaeanDark AgesherdsoctopusRhodesLouvreHistorical urban community sizesList of largest cities throughout historyhamletsvillagesManikaAgios DimitriosProto-GreekBronze Age GreecebronzecopperOld KingdomAeginaEuboeaLefkandipotter's wheelmegaronEutresis cultureKorakou cultureOlympia, GreeceHouse of the TilesGreeksTiryns cultureMinyansMinyan wareMiddle Kingdom of EgyptSpercheios RiverMesseniaHeinrich SchliemannMiddle Bronze Age migrationMycenaean GreeceLinear BLate MinoanLate HelladicMask of AgamemnonDendra panoplyShaft GravesLaconiaThera eruptiondark-on-lightThebanNew Kingdom of EgyptpharaohsHatshepsutThutmose IIIEighteenth DynastySpartaNichoriaBothrosAtreusMaşat HöyükHittiteAmarnaAmenhotep IIIAkhenatenUluburun shipwreckMiletusMursili IIMursili's eclipseElizabeth B. FrenchHittitesAssyria