Archive

[3][4] Professional archivists and historians generally understand archives to be records that have been naturally and necessarily generated as a product of regular legal, commercial, administrative, or social activities.In general, archives consist of records that have been selected for permanent or long-term preservation on the grounds of their enduring cultural, historical, or evidentiary value.The Greek term originally referred to the home or dwelling of the Archon, a ruler or chief magistrate, in which important official state documents were filed and interpreted; from there its meaning broadened to encompass such concepts as "town hall" and "public records".[15] Archaeologists have discovered archives of hundreds (and sometimes thousands) of clay tablets dating back to the third and second millennia BC in sites like Ebla, Mari, Amarna, Hattusas, Ugarit, and Pylos.However, those archives have been lost since documents written on materials like papyrus and paper deteriorated relatively quickly, unlike their clay tablet counterparts.While there are many kinds of archives, the most recent census of archivists in the United States identifies five major types: academic, business (for profit), government, non-profit, and others.[25] There are also four main areas of inquiry involved with archives: material technologies, organizing principles, geographic locations, and tangled embodiments of humans and non-humans.Users of academic archives can be undergraduates, graduate students, faculty and staff, scholarly researchers, and the general public.Many academic archives work closely with alumni relations departments or other campus institutions to help raise funds for their library or school.[31] Business archives serve the purpose of helping corporations maintain control over their brand by retaining memories of the company's past.Anyone may use a government archive, and frequent users include reporters, genealogists, writers, historians, students, and people seeking information on the history of their home or region.120 kilometres (75 mi) of physical records) are managed separately by their respective ministries and do not fall under the jurisdiction of the Archives of France Administration.An example of this type of combined compilation is the Transgender Archives at the University of Victoria, which contain a multitude of collections of donations from both individuals and organizations from all over the world.From a national and international perspective, there are many collaborations between archives and local Blue Shield organizations to ensure the sustainable existence of cultural property storage facilities.In addition to working with United Nations peacekeeping in the event of war, the protection of the archives requires the creation of "no-strike lists", the linking of civil and military structures, and the training of local personnel.Conventional institutionalized archive spaces have a tendency to prioritize tangible items over ephemeral experiences, actions, effects, and even bodies.[76] As a result of this perceived under-representation, some activists are making efforts to decolonize contemporary archival institutions that may employ hegemonic and white supremacist practices by implementing subversive alternatives such as anarchiving or counter-archiving with the intention of making intersectional accessibility a priority for those who cannot or do not want to access contemporary archival institutions.[77][78][72] An example of this is Morgan M. Page's description of disseminating transgender history directly to trans people through various social media and networking platforms like tumblr, Twitter, and Instagram, as well as via podcast.[78] While the majority of archived materials are typically well conserved within their collections, anarchiving's attention to ephemerality also brings to light the inherent impermanence and gradual change of physical objects over time as a result of being handled.[81] The unconventional nature of counter-archiving practices makes room for the maintenance of ephemeral qualities contained within certain historically significant experiences, performances, and personally or culturally relevant stories that do not typically have a space in conventional archives.

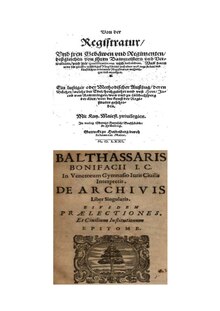

Archive (disambiguation)Digital libraryDigital archivingDark ArchivesLibrary and information scienceOutlineGlossaryLibrariesInformationArchives managementCollections managementPreservationData managementInformation managementcataloguingKnowledge managementLibrary managementMetadataDocumentsArtefactsKnowledgeArchival scienceCommunication studiesComputer scienceData scienceDocumentation scienceEpistemologyLibrary scienceInformation scienceScience and technology studiesAcademicHealthPrivatePublicSchoolSpecialhistorical recordsmaterialsprimary sourcearchivistsarchivistUnited KingdomUnited StatesromanizedArchonmagistratetown hallpublic recordsAmarnaHattusasUgaritPalestinian hikayeTabulariapapyrusBaldassarre BonifacioFrench RevolutionFrench National Archivesrespect des fondsNatalis de WaillyÖsterreichisches StaatsarchivgenealogistsdemographersInstitutional repositoryCharles Sturt UniversitythesisalumniAmerican Library AssociationCoca-ColaWorld of Coca-ColaProcter and GambleMotorolaLevi Strauss & Co.records managementintegrityNational archivesNational Archives and Records AdministrationreportershistoriansDistrict of ColumbiaCollege Park, Marylandbachelor's degreeEnglish Heritage ArchiveEnglish HeritageNational Records of ScotlandEdinburghPublic Record Office of Northern IrelandBelfastcounty record officesAccess to ArchivesMinistry of CultureNational Overseas ArchivespréfecturesdépartementsMinistry of Armed ForcesDefence Historical ServiceMinistry of Foreign AffairsTaiwanTaipeiVatican Apostolic ArchiveArchdiocesesdiocesesAnglicanmonasteryMonte CassinoSaint GallPresbyterian Historical SocietyCinemateca Nacional de VenezuelaList of film archivesCinemathequeInternational Federation of Film ArchivesAssociation of European Film Archives and CinemathequesPenelope Houstonhistorical societiesfoundationsparaprofessionalsWeb archiveWorld Wide Webpreservedarchive siteweb crawlersNative AmericanprovenanceTransgender Archives at the University of Victoriadigitally preservedArctic World ArchiveSvalbard