Stellar nucleosynthesis

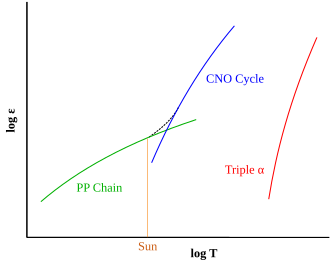

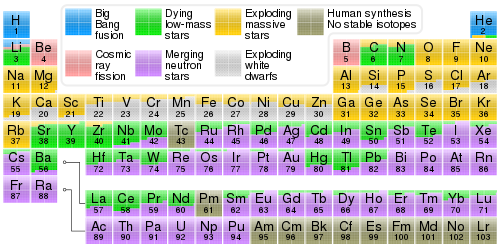

In astrophysics, stellar nucleosynthesis is the creation of chemical elements by nuclear fusion reactions within stars.Stellar nucleosynthesis has occurred since the original creation of hydrogen, helium and lithium during the Big Bang.[2] Further advances were made, especially to nucleosynthesis by neutron capture of the elements heavier than iron, by Margaret and Geoffrey Burbidge, William Alfred Fowler and Fred Hoyle in their famous 1957 B2FH paper,[3] which became one of the most heavily cited papers in astrophysics history.The term supernova nucleosynthesis is used to describe the creation of elements during the explosion of a massive star or white dwarf.However, most of the nucleosynthesis in the mass range A = 28–56 (from silicon to nickel) is actually caused by the upper layers of the star collapsing onto the core, creating a compressional shock wave rebounding outward.The shock front briefly raises temperatures by roughly 50%, thereby causing furious burning for about a second.A stimulus to the development of the theory of nucleosynthesis was the discovery of variations in the abundances of elements found in the universe.The need for a physical description was already inspired by the relative abundances of the chemical elements in the solar system.Those abundances, when plotted on a graph as a function of the atomic number of the element, have a jagged sawtooth shape that varies by factors of tens of millions (see history of nucleosynthesis theory).A second stimulus to understanding the processes of stellar nucleosynthesis occurred during the 20th century, when it was realized that the energy released from nuclear fusion reactions accounted for the longevity of the Sun as a source of heat and light.In 1928 George Gamow derived what is now called the Gamow factor, a quantum-mechanical formula yielding the probability for two contiguous nuclei to overcome the electrostatic Coulomb barrier between them and approach each other closely enough to undergo nuclear reaction due to the strong nuclear force which is effective only at very short distances.In 1939, in a Nobel lecture entitled "Energy Production in Stars", Hans Bethe analyzed the different possibilities for reactions by which hydrogen is fused into helium.The second process, the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen cycle, which was also considered by Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker in 1938, is more important in more massive main-sequence stars.That theory was begun by Fred Hoyle in 1946 with his argument that a collection of very hot nuclei would assemble thermodynamically into iron.[1] Hoyle followed that in 1954 with a paper describing how advanced fusion stages within massive stars would synthesize the elements from carbon to iron in mass.[3] This review paper collected and refined earlier research into a heavily cited picture that gave promise of accounting for the observed relative abundances of the elements; but it did not itself enlarge Hoyle's 1954 picture for the origin of primary nuclei as much as many assumed, except in the understanding of nucleosynthesis of those elements heavier than iron by neutron capture.In 1957 Cameron presented his own independent approach to nucleosynthesis,[14] informed by Hoyle's example, and introduced computers into time-dependent calculations of evolution of nuclear systems.There are two predominant processes by which stellar hydrogen fusion occurs: proton–proton chain and the carbon–nitrogen–oxygen (CNO) cycle.Ninety percent of all stars, with the exception of white dwarfs, are fusing hydrogen by these two processes.[21]: 245 In the cores of lower-mass main-sequence stars such as the Sun, the dominant energy production process is the proton–proton chain reaction.[22] Proton-proton chain with a dependence of approximately T^4, meaning the reaction cycle is highly sensitive to temperature; a 10% rise of temperature would increase energy production by this method by 46%, hence, this hydrogen fusion process can occur in up to a third of the star's radius and occupy half the star's mass.About 90% of the CNO cycle energy generation occurs within the inner 15% of the star's mass, hence it is strongly concentrated at the core.[27][a][28]: 357 [29][b] The type of hydrogen fusion process that dominates in a star is determined by the temperature dependency differences between the two reactions.The proton–proton chain reaction starts at temperatures about 4×106 K,[30] making it the dominant fusion mechanism in smaller stars.More massive stars ignite helium in their core without a flash and execute a blue loop before reaching the asymptotic giant branch.Such a star initially moves away from the AGB toward bluer colours, then loops back again to what is called the Hayashi track.In this way, the alpha process preferentially produces elements with even numbers of protons by the capture of helium nuclei.However, since the reaction involves quantum tunneling, there is an exponential damping at low energies that depends on Gamow factor EG, giving an Arrhenius equation:where S(E) depends on the details of the nuclear interaction, and has the dimension of an energy multiplied for a cross section.Note that typical core temperatures in main-sequence stars give kT of the order of keV.[39]: ch.

Proton–proton chain

(PP)

Combined energy generation of PP and CNO within a star

The Sun's core temperature, at which PP is more efficient

Logarithmic scaleProton–proton chainCNO cycleTriple-α processastrophysicscreationchemical elementsnuclear fusionoriginal creationhydrogenheliumlithiumBig Bangpredictive theoryobserved abundancesisotopesFred Hoyleneutron captureMargaretGeoffrey BurbidgeWilliam Alfred FowlerB2FH paperStars evolveburning hydrogenmain sequencehorizontal branchhigher elementsstellar windplanetary nebulasupernovasupernova nucleosynthesiswhite dwarfgravitational collapsecarbonoxygensiliconshock wavehistory of nucleosynthesis theoryenergyArthur EddingtonF.W. AstonJean PerrinGeorge GamowGamow factorquantum-mechanicalCoulomb barrierstrong nuclear forceAtkinsonHoutermansEdward TellerHans Betheproton–proton chain reactioncarbon–nitrogen–oxygen cycleCarl Friedrich von WeizsäckerBurbidgeFowlerAlastair G. W. CameronDonald D. Claytons-processr-processsupergiantDeuterium fusiontriple-alpha processalpha processLithium burningbrown dwarfsCarbon-burning processNeon-burning processOxygen-burning processSilicon-burning processNeutronProtonrp-processp-processPhotodisintegrationhelium-4main-sequencechemicaloxidizingwhite dwarfsdeuteriumenergy fluxradiative heat transferconvective heat transfercatalytic cycleneutrinoconvectiveradiative transferconvection zonered giant branchhelium flashdegenerateblue loopasymptotic giant branchHayashi trackCepheid variablesMilky Wayred supergiantsreaction rate constantde Broglie wavelengthquantum tunnelingArrhenius equationreduced massbeta decaydiprotonhalf-lifemain-sequence starsabundance of elementsNatureMonthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical SocietyBibcodeThe Astrophysical Journal Supplement SeriesReviews of Modern PhysicsThe ObservatoryHoboken, NJPhysical ReviewUniversity of Chicago PressScienceAtomic Energy of Canada LimitedAnnals of PhysicsPhysical Review LettersThe Astrophysical JournalBelmont, CAWadsworth Publishing CompanyBöhm-Vitense, ErikaCambridge University Press