Spanish–American War

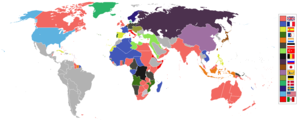

The Spanish–American War brought an end to almost four centuries of Spanish presence in the Americas, Asia, and the Pacific; the United States meanwhile not only became a major world power, but also gained several island possessions spanning the globe, which provoked rancorous debate over the wisdom of expansionism.But historian Andrea Pitzer also points to the actual shift toward savagery of the Spanish military leadership, who adopted the policies of "reconcentración" (use of concentration camps) and attacks on civilians after replacing the relatively conservative Governor-General of Cuba Arsenio Martínez Campos with the more unscrupulous and aggressive Valeriano Weyler, nicknamed "The Butcher."Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan was an exceptionally influential theorist; his ideas were much admired by future 26th President Theodore Roosevelt, as the U.S. rapidly built a powerful naval fleet of steel warships in the 1880s and 1890s.[35] Antonio Cánovas del Castillo, the architect of Spain's Restoration constitution and the prime minister at the time, ordered General Arsenio Martínez-Campos, a distinguished veteran of the war against the previous uprising in Cuba, to quell the revolt.[57] In total, 260[58] servicemen were killed in the initial explosion, and six more died shortly thereafter from injuries,[58] marking the greatest loss of life for the American military in a single day since the defeat at Little Bighorn 21 years earlier.[70] Public opinion nationwide did demand immediate action, overwhelming the efforts of President McKinley, Speaker of the House Thomas Brackett Reed, and the business community to find a negotiated solution.McKinley paid close attention to the strong antiwar consensus of the business community, and strengthened his resolve to use diplomacy and negotiation rather than brute force to end the Spanish tyranny in Cuba.[72] Historian Nick Kapur argues that McKinley's actions as he moved toward war were rooted not in various pressure groups but in his deeply held "Victorian" values, especially arbitration, pacifism, humanitarianism, and manly self-restraint.The financial security of those working and living in the cotton belt relied heavily upon trade across the Atlantic, which would be disrupted by a nautical war, the prospect of which fostered a reluctance to enlist.McKinley put it succinctly in late 1897 that if Spain failed to resolve its crisis, the United States would see "a duty imposed by our obligations to ourselves, to civilization and humanity to intervene with force".Political scientist Robert Osgood, writing in 1953, led the attack on the American decision process as a confused mix of "self-righteousness and genuine moral fervor," in the form of a "crusade" and a combination of "knight-errantry and national self- assertiveness.We have got a battleship in the harbor of Havana, and our fleet, which overmatches anything the Spanish have, is masked at the Dry Tortugas.In his autobiography,[93] Theodore Roosevelt gave his views of the origins of the war: Our own direct interests were great, because of the Cuban tobacco and sugar, and especially because of Cuba's relation to the projected Isthmian [Panama] Canal.Because of these considerations I favored war.In the 333 years of Spanish rule, the Philippines developed from a small overseas colony governed from the Mexico-based Viceroyalty of New Spain to a land with modern elements in the cities.[95] On April 23, 1898, a document from Governor General Basilio Augustín appeared in the Manila Gazette newspaper warning of the impending war and calling for Filipinos to participate on the side of Spain.They began working on the final wire and succeeded in partially cutting it until the still heavy Spanish fire and mounting casualties forced the Navy officer in command, Lieutenant E. A. Anderson, to order the boats to return to the cover of the larger vessels.U.S. Assistant Naval Constructor, Lieutenant Richmond Pearson Hobson was ordered by Rear Admiral William T. Sampson to sink the collier USS Merrimac in the harbor to bottle up the Spanish fleet.The American offensive began on May 12, 1898, when a squadron of 12 U.S. ships commanded by Rear Adm. William T. Sampson of the United States Navy attacked the archipelago's capital, San Juan.[150] Shortly after the war began in April, the Spanish Navy ordered major units of its fleet to concentrate at Cádiz in southern Spain to form the 2nd Squadron under the command of Rear Admiral Manuel de la Cámara y Livermoore.[151] Two of Spain's most powerful warships, the battleship Pelayo and the brand-new armored cruiser Emperador Carlos V, were not available when the war began—the former undergoing reconstruction in a French shipyard and the latter not yet delivered from her builders—but both were rushed into service and assigned to Cámara's squadron.Spanish Minister of Marine Ramón Auñón y Villalón made plans for Cámara to take a portion of his squadron across the Atlantic Ocean and bombard a city on the East Coast of the United States, preferably Charleston, South Carolina, and then head for the Caribbean to make port at San Juan, Havana, or Santiago de Cuba,[153] but in the end this idea was dropped.The medical crisis of the Spanish–American War had far-reaching consequences:[175] More soldiers died from disease than from combat (fewer than 400 killed in action vs. thousands from illness) This led to significant reforms in military medicine and sanitation practices.[182] The war redefined national identity, served as a solution of sorts to the social divisions plaguing the American mind, and provided a model for all future news reporting.This massive flow of capital (equivalent to 25% of the gross domestic product of one year) helped to develop the large modern firms in Spain in the steel, chemical, financial, mechanical, textile, shipyard, and electrical power industries.[citation needed] Thus, despite that Cuba technically gained its independence after the war ended, the United States government ensured that it had some form of power and control over Cuban affairs.[198] The notion of the United States as an imperial power, with colonies, was hotly debated domestically with President McKinley and the Pro-Imperialists winning their way over vocal opposition led by Democrat William Jennings Bryan,[198] who had supported the war.[204] Article IX of The Treaty of Paris stated that the U.S. Congress were responsible for decisions regarding the civil and political rights of the indigenous populations of the newly acquired territories of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam.The moment has come for us to show the world that we are more than courageous to triumph over those, who, feigning to be loyal friends, took advantage of our misfortunes and capitalized on our nobility by making use of the means civilized nations consider as condemnable and contemptible.The Americans, gratified with their social progress, have drained off our patience and have instigated the war through wicked tactics, treacherous acts, and violations of human rights and internal agreements.Spain, counting on the sympathies of all nations, will come out in triumph from this new test, by shattering and silencing the adventurers of those countries which, without cohesiveness and post, offer to humanity shameful traditions and the ungrateful spectacle of some embassies within which jointly dwell intrigues and defamation, cowardice and cynicism.Prepare yourself for the battle and united together under the glorious Spanish flag, always covered with laurels, let us fight, convinced that victory will crown our efforts and let us reply the intimations of our enemies with a decision befitting a Christian and patriot, with a cry of "Long live Spain!"

decolonization of the AmericasCuban War of IndependencePhilippine RevolutionSignal CorpsUSS IowaNew York Harborpith helmetsManilaTreaty of ParisRooseveltRough RidersSan Juan HillSpanish flagFort San Antonio AbadPuerto RicoCaribbean SeaPhilippinesPhilippine SeaTreaty of Paris of 1898First Philippine RepublicPhilippine–American WarSpain sells to GermanySpanish EmpireAmericasUnited StatesCuban Liberation ArmyPhilippine RevolutionariesDictatorial GovernmentRevolutionary GovernmentCaptaincy General of CubaCaptaincy General of the PhilippinesCaptaincy General of Puerto RicoWilliam McKinleyRussell A. AlgerJohn Davis LongLuther HareNelson MilesTheodore RooseveltWilliam ShafterFitzhugh LeeGeorge DeweyWilliam SampsonWesley MerrittJoseph WheelerCharles SigsbeeMáximo GómezCalixto GarcíaDemetrio DuanyEmilio AguinaldoApolinario MabiniBaldomero AguinaldoAntonio LunaAlfonso XIIIPráxedes Mateo SagastaPatricio MontojoPascual CerveraArsenio LinaresManuel de la CámaraManuel MacíasRamón BlancoAntero RubínArsenio MartínezValeriano WeylerJosé ToralBasilio AugustínFermín JáudenesDiego de los RíosBanana Wars1st U.S. occupation2nd U.S. occupationNegro RebellionSugar InterventionPuerto Rican campaignHondurasFirst Honduran Civil WarSecond Honduran Civil WarNicaraguaMasayaCoyotepe Hill1926–1927 civil warLa Paz CentroOcotalSan FernandoSanta ClaraTelpanecaSapotillal2nd Las CrucesEl BramaderoLa FlorAchuapaAgua CartaEl SauceMexicoBorder WarVeracruzFort DipitieFort Rivière1st Port-au-Prince2nd Port-au-PrinceDominican RepublicSanto DomingoPuerto PlataLas TrencherasGuayacanasSan Francisco de MacorisUSS MaineHavana Harborsovereigntyprotectorateexpansionismyellow journalismArsenio Martínez CamposGrover ClevelandU.S. Navyat Manila BayBattles of El CaneyGuam surrenderedlanded on Puerto Rico1898 Treaty of ParisGeneration of '98Peninsular Warcolonies in the AmericasSpanish American wars of independenceCarlist WarsAntonio Cánovas del CastilloEmilio Castelar