Rich man and Lazarus

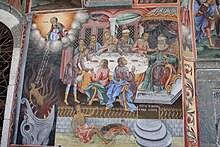

But there was a certain beggar named Lazarus, full of sores, who was laid at his gate, desiring to be fed with the crumbs which fell from the rich man's table."Then he cried and said, 'Father Abraham, have mercy on me, and send Lazarus that he may dip the tip of his finger in water and cool my tongue; for I am tormented in this flame.'[10][11][12] Supporters of this view point to a key detail in the story: the use of a personal name (Lazarus) not found in any other parable.For the corpse of the rich man is without doubt not in hell, but buried in the earth; it must however be a place where the soul can be and has no peace, and it cannot be corporeal.(From the Talmud and Hebraica, Volume 3)[18]E. W. Bullinger in the Companion Bible cited Lightfoot's comment,[19] and expanded it to include coincidence to lack of belief in the resurrection of the historical Lazarus (John 12:10).[27] Anglican theologian Simon Perry has argued that the Lazarus of the parable (an abbreviated transcript of "Eleazer") refers to Eliezer of Damascus, Abraham's servant.Lazarus was poor, despised, racked with pain and hunger while he was on earth; but when he died, angels carried his soul to the abode of the just, where he received consolation."He was esteemed and honoured, surrounded by flatterers, waited on by a host of servants, clad in costly clothes, and he feasted luxuriously every day.[31] Most Christians believe in the immortality of the soul and particular judgment and see the story as consistent with it, or even refer to it to establish these doctrines as St. Irenaeus, an Early Church father, did.[33] Proponents of the mortality of the soul, and general judgment, for example Advent Christians, Conditionalists, Seventh-day Adventists, Jehovah's Witnesses, Christadelphians, and Christian Universalists, argue that this is a parable using the framework of Jewish views of the Bosom of Abraham, and is metaphorical, and is not definitive teaching on the intermediate state for several reasons.[36] We have in fact one of the cases where the background to the teaching is more probably found in non-biblical sources.Some scholars—e.g., G. B. Caird,[37] Joachim Jeremias,[38] Marshall,[39] Hugo Gressmann,[40]—suggest the basic storyline of The Rich Man and Lazarus was derived from Jewish stories that had developed from an Egyptian folk tale about Si-Osiris.The story was often shown in art, especially carved at the portals of churches, at the foot of which beggars would sit (for example at Moissac and Saint-Sernin, Toulouse), pleading their cause.[49] In the Latin liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, the words of In paradisum are sometimes chanted as the deceased is taken from church to burial, including this supplication: "Chorus angelorum te suscipiat ... et cum Lazaro quondam paupere aeternam habeas requiem" (May the ranks of angels receive you ... and with Lazarus, who was once poor, may you have eternal rest")."[57] In William Shakespeare's Henry IV, Part 1, Sir John Falstaff alludes to the story while insulting his friend Bardolph about his face, comparing it to a memento mori: "I never see thy face," he says "but I think upon hell-fire and Dives that lived in purple; for there he is in his robes, burning, burning" (III, 3, 30–33)."Dives Malus" (the wicked rich man) also known as "Historia Divitis" (c. 1640) by Giacomo Carissimi is a Latin paraphrase of the Luke text, set as an oratorio for 2 sopranos, tenor, bass; for private performance in the oratories of Rome in the 1640s.[64] The story appeared as an English folk song whose oldest written documentation dates from 1557,[65] with the depiction of the afterlife altered to fit Christian tradition.[66] Ralph Vaughan Williams based his orchestral piece Five Variants of Dives and Lazarus (1939) on this folk song,[67] and also used an arrangement as the hymn tune Kingsfold.

Lazarus of BethanyDives and Lazarus (ballad)LazarusCodex Aureus of EchternachCatholic ChurchPatronagelepersOrder of Saint Lazarusparable of Jesus16th chapterGospel of Lukehis disciplesPhariseesAbrahamTen VirginsProdigal SonGood Samaritanmedieval artafterlifeEadwine PsalterMorgan LibraryGustave DoréQ documentJeromeTom WrightJoachim JeremiasMartin LutherFyodor BronnikovJohn LightfootPhariseeBosom of AbrahamE. W. BullingersatiricalSadduceesProphetical books of the BibleAbbé DriouxAnglicanEliezerepicureanJames Tissotimmortality of the soulparticular judgmentSt. IrenaeusChristian mortalismsoul sleepgeneral judgmentLast JudgmentAnglicansSeventh-day AdventistsJehovah's WitnessesChristadelphiansUniversalistsmetaphoricalI. Howard MarshallG. B. CairdHugo Gressmannstorylinefolk taleRichard BauckhamRila MonasteryHippolytus of Romelake of fireBook of RevelationPeter Chrysologusmedievalparablepatron saintcrusadersKingdom of JerusalemMoissacSaint-Sernin, ToulouseBourges CathedralIn paradisumHebrewEleazarGospel of JohnresurrectsRomanesqueBurgundyChurch of St. TrophimeAvallonVézelaycathedral of AutunGeoffrey ChaucerSummonerWilliam ShakespeareHenry IV, Part 1Sir John Falstaffmemento moriHenry VElizabeth GaskellMary BartonCharles DickensHard TimesA Christmas CarolThe ChimesHerman MelvilleMoby-DickThe Love Song of J. Alfred PrufrockT. S. EliotRichard CrashawmetaphysicalEdith SitwellThe BlitzLondonWorld War IIChristHeinrich SchützoratorioGiacomo CarissimioratoriesJohann Philipp FörtschChild BalladDives and LazarusRalph Vaughan WilliamsFive Variants of Dives and LazarusBenjamin BrittenJosh Whiteorder of chivalryKnights HospitallerLatin Kingdom of JerusalemleprosyJerusalemTemplarsHospitallersmilitary orders