Monocotyledon

Monocotyledons (/ˌmɒnəˌkɒtəˈliːdənz/),[d][13][14] commonly referred to as monocots, (Lilianae sensu Chase & Reveal) are grass and grass-like flowering plants (angiosperms), the seeds of which typically contain only one embryonic leaf, or cotyledon.On the one hand, the organization of the shoots, leaf structure, and floral configuration are more uniform than in the remaining angiosperms, yet within these constraints a wealth of diversity exists, indicating a high degree of evolutionary success.[17] Monocot diversity includes perennial geophytes such as ornamental flowers including orchids (Asparagales); tulips and lilies (Liliales); rosette and succulent epiphytes (Asparagales); mycoheterotrophs (Liliales, Dioscoreales, Pandanales), all in the lilioid monocots; major cereal grains (maize, rice, barley, rye, oats, millet, sorghum and wheat) in the grass family; and forage grasses (Poales) as well as woody tree-like palm trees (Arecales), bamboo, reeds and bromeliads (Poales), bananas and ginger (Zingiberales) in the commelinid monocots, as well as both emergent (Poales, Acorales) and aroids, as well as floating or submerged aquatic plants such as seagrass (Alismatales).Despite these limitations a wide variety of adaptive growth forms has resulted (Tillich, Figure 2) from epiphytic orchids (Asparagales) and bromeliads (Poales) to submarine Alismatales (including the reduced Lemnoideae) and mycotrophic Burmanniaceae (Dioscreales) and Triuridaceae (Pandanales).Other forms of adaptation include the climbing vines of Araceae (Alismatales) which use negative phototropism (skototropism) to locate host trees (i.e. the darkest area),[24] while some palms such as Calamus manan (Arecales) produce the longest shoots in the plant kingdom, up to 185 m long.[31] The evolution of this monocot characteristic has been attributed to developmental differences in early zonal differentiation rather than meristem activity (leaf base theory).Such optical signalling is usually a function of the tepal whorls but may also be provided by semaphylls (other structures such as filaments, staminodes or stylodia which have become modified to attract pollinators).Broad leaves and reticulate leaf veins, features typical of dicots, are found in a wide variety of monocot families: for example, Trillium, Smilax (greenbriar), Pogonia (an orchid), and the Dioscoreales (yams).Many monocots are herbaceous and do not have the ability to increase the width of a stem (secondary growth) via the same kind of vascular cambium found in non-monocot woody plants.He observed that the majority had broad leaves with net-like venation, but a smaller group were grass-like plants with long straight parallel veins.Such which neither spring out of the ground with seed leaves nor have their pulp divided into lobes Since this paper appeared a year before the publication of Malpighi's Anatome Plantarum (1675–1679), Ray has the priority.Mense quoque Maii, alias seminales plantulas Fabarum, & Phaseolorum, ablatis pariter binis seminalibus foliis, seu cotyledonibus, incubandas posuiIn the month of May, also, I incubated two seed plants, Faba and Phaseolus, after removing the two seed leaves, or cotyledons In this experiment, Malpighi also showed that the cotyledons were critical to the development of the plant, proof that Ray required for his theory.This approach, also referred to as polythetic would last till evolutionary theory enabled Eichler to develop the phyletic system that superseded it in the late nineteenth century, based on an understanding of the acquisition of characteristics.[57][58][59] He also made the crucial observation Ex hac seminum divisione sumum potest generalis plantarum distinctio, eaque meo judicio omnium prima et longe optima, in eas sci.[h][33] In De Jussieu's system (1789), he followed Ray, arranging his Monocotyledones into three classes based on stamen position and placing them between Acotyledones and Dicotyledones.[74] The establishment of major new clades necessitated a departure from the older but widely used classifications such as Cronquist and Thorne, based largely on morphology rather than genetic data.[75][76] This DNA based molecular phylogenetic research confirmed on the one hand that the monocots remained as a well defined monophyletic group or clade, in contrast to the other historical divisions of the flowering plants, which had to be substantially reorganized.Amborellales Nymphaeales Austrobaileyales magnoliids Chloranthales monocots Ceratophyllales eudicots While the monocotyledons have remained extremely stable in their outer borders as a well-defined and coherent monophylectic group, the deeper internal relationships have undergone considerable flux, with many competing classification systems over time.[84] A major advance in this respect was the work of Rolf Dahlgren (1980),[85] which would form the basis of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group's (APG) subsequent modern classification of monocot families.Dahlgren who used the alternate name Lilliidae considered the monocots as a subclass of angiosperms characterised by a single cotyledon and the presence of triangular protein bodies in the sieve tube plastids.With respect to the specific issue regarding Liliales and Asparagales, Dahlgren followed Huber (1969)[86] in adopting a splitter approach, in contrast to the longstanding tendency to view Liliaceae as a very broad sensu lato family.In the following cladogram numbers indicate crown group (most recent common ancestor of the sampled species of the clade of interest) divergence times in mya (million years ago).For a very long time, fossils of palm trees were believed to be the oldest monocots,[98] first appearing 90 million years ago (mya), but this estimate may not be entirely true.[104][105] Similarly, Wikström et al.,[106] using Sanderson's non-parametric rate smoothing approach,[107] obtained ages of 127–141 million years for the crown group of monocots.[108] All these estimates have large error ranges (usually 15-20%), and Wikström et al. used only a single calibration point,[106] namely the split between Fagales and Cucurbitales, which was set to 84 Ma, in the late Santonian period.[127] The phylogenetic position of Alismatales (many water), which occupy a relationship with the rest except the Acoraceae, do not rule out the idea, because it could be 'the most primitive monocots' but not 'the most basal'.Some monocots, such as grasses, have hypogeal emergence, where the mesocotyl elongates and pushes the coleoptile (which encloses and protects the shoot tip) toward the soil surface.[135] Monocots are among the most important plants economically and culturally, and account for most of the staple foods of the world, such as cereal grains and starchy root crops, and palms, orchids and lilies, building materials, and many medicines.[43] Of the monocots, the grasses are of enormous economic importance as a source of animal and human food,[84] and form the largest component of agricultural species in terms of biomass produced.[96][136] Other economically important monocotyledon crops include various palms (Arecaceae), bananas and plantains (Musaceae), gingers and their relatives, turmeric and cardamom (Zingiberaceae), asparagus (Asparagaceae), pineapple (Bromeliaceae), sedges (Cyperaceae) and rushes (Juncaceae), vanilla (Orchidaceae), yam (Dioscoreaceae), taro (Araceae), and leeks, onion and garlic (Amaryllidaceae).

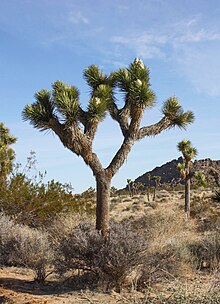

Early CretaceousPreꞒdate palmZostera marinaPandanus heterocarpusgingerScientific classificationPlantaeTracheophytesAngiospermsType genusLiliumalismatid monocotsAcoralesAlismataleslilioid monocotsAsparagalesDioscorealesLilialesPandanalesPetrosavialescommelinidArecalesCommelinalesPoalesZingiberalesSynonymsBesseyLilianaeTakht.CronquistW.Zimm.LiliidaeLiliopsidaBatschEichlerE.Morrenflowering plantscotyledondicotyledonstaxonomic ranksAPG III systemfamilyOrchidaceaePoaceaesedgesagriculturebiomassgrainsforagesugar canebamboosAllium crenulatumperianthbody planaquatic habitatsradiationcladesdiversityperennialgeophytesornamental flowersorchidstulipsliliesepiphytesmycoheterotrophscerealbarleymilletsorghumgrass familypalm treesbamboobromeliadsbananascommelinid monocotsaroidsaquatic plantsseagrasslateral meristemcambiumsecondary growtharboraceousagavespandansinternodegrowth formsepiphyticLemnoideaemycotrophicBurmanniaceaeTriuridaceaeAraceaeskototropismCalamus manantherophytelife formLeaf venationrunnersrhizomesvegetative propagationinternodesscale leavestubersinflorescencesCrocosmiaperigonetrimerouswhorlstepalscorollacorollineAnthesisthermonasticzoophilousinsectssemaphyllsfilamentsstaminodesstylodiabractsvascular bundlesYucca brevifoliamonocotseudicots