Mahayana

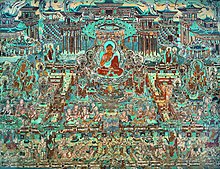

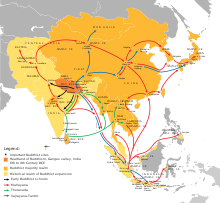

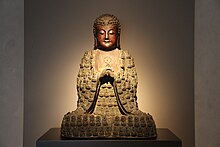

'Great Vehicle'; Chinese: 大乘; Vietnamese: Đại thừa) is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices developed in ancient India (c. 1st century BCE onwards).This view states that laypersons were particularly important in the development of Mahāyāna and is partly based on some texts like the Vimalakirti Sūtra, which praise lay figures at the expense of monastics.Warder and Paul Williams who argue that at least some Mahāyāna elements developed among Mahāsāṃghika communities (from the 1st century BCE onwards), possibly in the area along the Kṛṣṇa River in the Āndhra region of southern India.[31][note 3][32] The Mahāsāṃghika origins theory has also slowly been shown to be problematic by scholarship that revealed how certain Mahāyāna sutras show traces of having developed among other nikāyas or monastic orders (such as the Dharmaguptaka).[17][36] Jan Nattier's study of the Ugraparipṛcchā Sūtra, A few good men (2003) argues that this sutra represents the earliest form of Mahāyāna, which presents the bodhisattva path as a 'supremely difficult enterprise' of elite monastic forest asceticism.This figure is widely praised as someone who should be respected, obeyed ('as a slave serves his lord'), and donated to, and it is thus possible these people were the primary agents of the Mahāyāna movement.[17] Some important evidence for early Mahāyāna Buddhism comes from the texts translated by the Indoscythian monk Lokakṣema in the 2nd century CE, who came to China from the kingdom of Gandhāra.[24] One reason for this view is that Mahāyāna sources are extremely diverse, advocating many different, often conflicting doctrines and positions, as Jan Nattier writes:[53]Thus we find one scripture (the Aksobhya-vyuha) that advocates both srávaka and bodhisattva practices, propounds the possibility of rebirth in a pure land, and enthusiastically recommends the cult of the book, yet seems to know nothing of emptiness theory, the ten bhumis, or the trikaya, while another (the P'u-sa pen-yeh ching) propounds the ten bhumis and focuses exclusively on the path of the bodhisattva, but never discusses the paramitas.[39][40] By the fourth century, Chinese monks like Faxian (c. 337–422 CE) had also begun to travel to India (now dominated by the Guptas) to bring back Buddhist teachings, especially Mahāyāna works.Some scholars like Alexis Sanderson argue that Vajrayāna derives its tantric content from Shaivism and that it developed as a result of royal courts sponsoring both Buddhism and Saivism.[note 9] Mahāyāna constitutes an inclusive and broad set of traditions characterized by plurality and the adoption of a vast number of new sutras, ideas and philosophical treatises in addition to the earlier Buddhist texts.Suzuki described the broad range and doctrinal liberality of Mahāyāna as "a vast ocean where all kinds of living beings are allowed to thrive in a most generous manner, almost verging on a chaos".The White Lotus Sutra famously describes the lifespan of the Buddha as immeasurable and states that he actually achieved Buddhahood countless of eons (kalpas) ago and has been teaching the Dharma through his numerous avatars for an unimaginable period of time.[90] Mahāyāna Buddhists generally hold that pursuing only the personal release from suffering i.e. nirvāṇa is a smaller or inferior aspiration (called "hinayana"), because it lacks the wish and resolve to liberate all other sentient beings from saṃsāra (the round of rebirth) by becoming a Buddha.[106][5] Other sutras (like the Daśabhūmika) give a list of ten, with the addition of upāya (skillful means), praṇidhāna (vow, resolution), Bala (spiritual power) and Jñāna (knowledge).According to Paul Williams, in these systems, the first bhūmi is reached once one attains "direct, nonconceptual and nondual insight into emptiness in meditative absorption", which is associated with the path of seeing (darśana-mārga).[110] The idea is most famously expounded in the White Lotus Sutra, and refers to any effective method or technique that is conducive to spiritual growth and leads beings to awakening and nirvana.[123][117] Attaining a state of fearless receptivity (ksanti) through the insight into the true nature of reality (Dharmatā) in an intuitive, non-conceptual manner is said to be the prajñāpāramitā, the highest spiritual wisdom.vijñapti-mātra, "perceptions only" and citta-mātra "mind only") is another important doctrine promoted by some Mahāyāna sutras which later became the central theory of a major philosophical movement which arose during the Gupta period called Yogācāra.Instead, the ultimate truth (paramārtha-satya) is said to be the view that all things (dharmas) are only mind (citta), consciousness (vijñāna) or perceptions (vijñapti) and that seemingly "external" objects (or "internal" subjects) do not really exist apart from the dependently originated flow of mental experiences.Another central practice advocated by numerous Mahāyāna sources is focused around "the acquisition of merit, the universal currency of the Buddhist world, a vast quantity of which was believed to be necessary for the attainment of Buddhahood".[160] Indian Mahayana Buddhist practice included numerous elements of devotion and ritual, which were considered to generate much merit (punya) and to allow the devotee to obtain the power or spiritual blessings of the Buddhas and bodhisattvas.[179] The Yogācārabhūmi-Śāstra (compiled c. 4th century), which is the most comprehensive Indian treatise on Mahāyāna practice, discusses classic Buddhist numerous meditation methods and topics, including the four dhyānas, the different kinds of samādhi, the development of insight (vipaśyanā) and tranquility (śamatha), the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthāna), the five hindrances (nivaraṇa), and classic Buddhist meditations such as the contemplation of unattractiveness, impermanence (anitya), suffering (duḥkha), and contemplation death (maraṇasaṃjñā).[38] Regarding religious praxis, David Drewes outlines the most commonly promoted practices in Mahāyāna sutras were seen as means to achieve Buddhahood quickly and easily and included "hearing the names of certain Buddhas or bodhisattvas, maintaining Buddhist precepts, and listening to, memorizing, and copying sutras, that they claim can enable rebirth in the pure lands Abhirati and Sukhavati, where it is said to be possible to easily acquire the merit and knowledge necessary to become a Buddha in as little as one lifetime."[193] Some Mahāyāna sutras also warn against the accusation that they are not the word of the Buddha (buddhavacana), such as the Astasāhasrikā (8,000 verse) Prajñāpāramitā, which states that such claims come from Mara (the evil tempter).Dating back at least to the Saṃdhinirmocana Sūtra is a classification of the corpus of Buddhism into three categories, based on ways of understanding the nature of reality, known as the "Three Turnings of the Dharma Wheel".[215] In modern China, the reform and opening up period in the late 20th century saw a particularly significant increase in the number of converts to Chinese Buddhism, a growth which has been called "extraordinary".[227] Cholvijarn observes that prominent figures associated with the Self perspective in Thailand have often been famous outside scholarly circles as well, among the wider populace, as Buddhist meditation masters and sources of miracles and sacred amulets.They point out that unlike the now-extinct Sarvāstivāda school, which was the primary object of Mahāyāna criticism, the Theravāda does not claim the existence of independent entities (dharmas); in this it maintains the attitude of early Buddhism.[235][236][237] Adherents of Mahāyāna Buddhism disagreed with the substantialist thought of the Sarvāstivādins and Sautrāntikas, and in emphasizing the doctrine of emptiness, Kalupahana holds that they endeavored to preserve the early teaching.

Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā SūtraNalandaMaitreyaFive TathāgatasBodhisattvaBuddhahoodMind of AwakeningBuddha-natureSkillful MeansTranscendent WisdomTranscendent VirtuesTwo truthsThree bodiesThree vehiclesOne VehicleBodhisattva PreceptsBodhisattva vowBodhisattva stagesPure LandsLuminous mindDharaniThree TurningsBuddhasBodhisattvasShakyamuniAmitabhaAdi-BuddhaAkshobhyaPrajñāpāramitā DevīBhaiṣajyaguruVairocanaMañjuśrīAvalokiteśvaraVajrapāṇiVajrasattvaKṣitigarbhaĀkāśagarbhaSamantabhadraWrathful deitiesMahayana sutrasPrajñāpāramitā sūtrasLotus SūtraBuddhāvataṃsaka SūtraMahāratnakūṭa SūtraMahāsaṃnipāta SūtraVimalakirtinirdeśaLalitavistara SūtraSamādhirāja SūtraSaṃdhinirmocana SūtraTathāgatagarbha sūtrasŚrīmālādevī SūtraMahāparinirvāṇa SūtraŚūraṅgama Samādhi SūtraLaṅkāvatāra SūtraGhanavyūha sūtraGolden Light SutraTathāgataguhyaka SūtraKāraṇḍavyūha SūtraMādhyamakaYogācāraTiantaiTendaiHuayanShingonPure LandNichirenVajrayānaTibetan BuddhismDzogchenFo Guang ShanTzu ChiDharma Drum MountainChung Tai ShanNāgārjunaAshvaghoshaĀryadevaLokakṣemaKumārajīvaAsangaVasubandhuSthiramatiBuddhapālitaDignāgaBhāvavivekaDharmakīrtiCandrakīrtiBodhidharmaHuinengShandaoXuanzangFazangAmoghavajraSaichōKūkaiShāntidevaShāntarakshitaWohnyoMazu DaoyiDahui ZonggaoHongzhi ZhengjueHōnenShinranDōgenŚaṅkaranandanaVirūpaRatnākaraśāntiAbhayākaraguptaNāropāAtishaSakya PanditaDolpopaRangjung DorjeTsongkhapaLongchenpaHakuinHanshanD. T. SuzukiSheng-yen14th Dalai LamaThích Nhất HạnhHan ChineseTaiwanVietnamTibetanBhutanMongolia