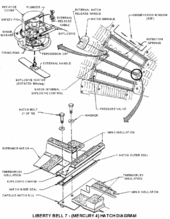

Mercury-Redstone 4

The flight went as expected until just after splashdown, when the hatch cover, designed to release explosively in the event of an emergency, accidentally blew.Both the pop-off hatch and the lanyard are standard features of ejection seats used in military aircraft, but in the Mercury design, the pilot still had to exit the craft himself, or be removed by emergency personnel.The quick release latching hatch weighed 69 lb (31 kg), too much of a weight addition to use on the orbital version of the spacecraft.When the MDF was ignited, the resulting gas pressure between the inner and outer seal would cause the bolts to fail in tension.Before the Mercury-Redstone 4 mission, Lewis Research Center and Space Task Group engineers had determined that firing the posigrade rockets into the booster-spacecraft adapter, rather than in the open, developed 78 percent greater thrust.The fairing changes and additional foam were used to reduce vibrations the pilot experienced during the boost phase of flight.[2] In January 1961, NASA's Director of the Space Task Group, Robert Gilruth, told Gus Grissom that he would be the primary pilot for Mercury-Redstone 4.On the morning of July 21, 1961, Gus Grissom entered the Liberty Bell 7 at 8:58 UTC and the 70 hatch bolts were put in place.Grissom later admitted at the postflight debriefing that he was "a bit scared" at liftoff, but he added that he soon gained confidence along with the acceleration increase.Grissom's cabin pressure sealed off at the proper altitude, about 27,000 ft (8.2 km), and he felt elated that the environmental control system was in good working order.During a 3 g (29 m/s2) acceleration on the up-leg of his flight, Grissom noticed a sudden change in the color of the horizon from light blue to jet black.The Redstone coasted for 10 seconds after its engine cut off; then a sharp report signaled that the posigrade rockets were popping the spacecraft loose from the booster.He told Shepard back in Mercury Control that the panorama of Earth's horizon, presenting an 800 mi (1,300 km) arc at peak altitude, was fascinating.[3] Turning reluctantly to his dials and control stick, Grissom made a pitch movement change, but was past his desired mark.Some land beneath the clouds (later determined to be western Florida around the Apalachicola area) appeared in the hazy distance, but the pilot was unable to identify it.Suddenly Cape Canaveral came into view so clearly that Grissom found it hard to believe that his slant-range was over 150 mi (240 km).Retrofire gave him the distinct and peculiar feeling that he had reversed his backward flight through space and was actually moving face forward.Meanwhile, he continued to report to the Mercury Control Center on his electric current reading, fuel quantity, acceleration, and other instrument indications.The spacecraft gradually righted itself, and, as the window cleared the water, Grissom jettisoned the reserve parachute and activated the rescue aids switch.The neck dam did not unroll easily; Grissom tinkered with his suit collar to ensure his buoyancy in the event that he had to get out of the spacecraft quickly.When the recovery helicopters, which had taken to the air at launch time and visually followed the contrails and parachute descent, were still about 2 mi (3.2 km) from the impact point, which was only 3 mi (4.8 km) beyond the bullseye, Lieutenant James L. Lewis, the pilot of the primary recovery helicopter, radioed Grissom to ask if he was ready for pickup.He had earlier unbuckled himself from most of his harness; he now removed his helmet, grasped the instrument panel with his right hand, and climbed though the hatchway.The copilot of the nearest recovery helicopter said that as he was preparing, per procedure, to cut off the spacecraft's antenna whip with a squib-actuated cutter at the end of a pole, the hatch cover flew off, struck the water about 5 ft (1.5 m) away, then skipped over the waves.The capsule sank out of sight, but the pickup pole tangled as the attached cable went taut, indicating to the helicopter pilots that they had made the catch.Reinhard immediately prepared to pass the floating astronaut the personnel hoist, but at that moment Lewis called a warning that a detector light had flashed on the instrument panel, indicating that metal chips were in the oil sump because of engine strain.Considering the implication of impending engine failure, Lewis told Reinhard to retract the personnel hoist while he called the second helicopter to retrieve Grissom.An independent technical review of the incident between August and October 1961 raised doubts regarding the theory that Grissom had blown the hatch and was responsible for the loss of the spacecraft.The spacecraft was found after a 14-year effort by Newport at a depth of nearly 16,000 ft (4,900 m),[9] 300 nmi (350 mi; 560 km) east-southeast of Cape Canaveral.[8] After Liberty Bell 7 was secured on the deck of the recovery ship, the "Ocean Project", experts removed and disposed of an explosive device (SOFAR bomb) that was supposed to detonate in the event of the spacecraft's sinking, but which failed to explode.[13] Philip Kaufman's 1983 film The Right Stuff includes a dramatization of the Liberty Bell 7 mission in which Fred Ward played Gus Grissom.

McDonnell AircraftVirgil I. GrissomRedstone MRLVCape CanaveralUSS RandolphProject MercuryMercury-Redstone 3Mercury-Atlas 6United Stateshuman spaceflightsuborbitalMercury-Redstone Launch VehiclecapsuleastronautVirgil "Gus" GrissomAtlantic OceansplashdownU.S. NavyhelicopterRedstone rocketsuborbital flightportholesFreedom 7Liberty BellPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania.ejection seatschimpanzeeCorning Glass WorksCorning, New Yorkcontrol of spacecraft attitudeLewis Research CenterSpace Task Groupseven original astronauts selected for MercuryAlan ShepardRobert GilruthGus GrissomJohn GlennCape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 5drogue parachutegrease pencilfathomsAstronaut OfficeGeminiApolloWally SchirraSigma 7Guenter WendtApollo 1Ed WhiteRoger B. ChaffeeCosmosphereHutchinson, KansasOceaneering InternationalApollo 11Discovery ChannelMercury dimesSOFAR bombThe Children's Museum of IndianapolisPhilip KaufmanThe Right StuffFred WardFrom the Earth to the MoonMark RolstonHidden FiguresNational Aeronautics and Space AdministrationWayback MachineSpace raceSpace flightFriendship 7Aurora 7Faith 7Freedom 7 IILittle Joe 1Big Joe 1Beach AbortLittle Joe 5Flown non-humanMiss SamMercury SevenScott CarpenterGordon CooperDeke SlaytonNavy Mark IVMercury-AtlasMercury-RedstoneMercury-ScoutMercury-JupiterMcDonnell Aircraft CorporationConvairChryslerNorth American AviationRedstoneBlue Scout IILittle JoeJupiterWallops IslandWallops Flight FacilityCape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 14Mercury Control CenterVostokManned Space Flight NetworkMercury spacesuitAstronaut Wives ClubMercury 13