Hand-held camera

To prevent shaky shots, a number of image stabilization technologies have been used on hand-held cameras including optical, digital and mechanical methods.The first silent film era movie cameras that could be carried by the cameraman were bulky and not very practical to simultaneously support, aim, and crank by hand, yet they were sometimes used in that way by pioneering filmmakers.In the 1890s, brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière developed the fairly compact Cinematograph which could be mounted on a tripod or carried by the cameraman, and it also served as the film projector.They were specifically designed to hold shorter lengths of film—usually 100 to 200 feet (30 to 60 m)—and were driven by hand-wound mainspring clockworks which could last continuously through most or even all of a film roll on one winding.The spring-wound cameras were also not accurate enough speed-wise to guarantee perfect sync speed, which led to many of them having motors installed (the additional sound being negligible).Most of these cameras saw steady usage during World War II by both sides for documentary purposes, and the Eyemos and Arriflexes in particular were mass manufactured for the Allied and Axis militaries, respectively.This allowed these cameras to be exposed to a much greater number of individuals than would have normally familiarized themselves with them; many wartime cameramen would eventually bring them back into the film industry where they are used to this day.This trend, led by Michel Brault, was followed by Raoul Coutard's work in the French New Wave and the cinéma vérité, "fly-on-the-wall" documentary film aesthetic.Pennebaker actually had to force the 16 mm technology forward themselves through a number of extensive camera and audio recording equipment modifications in order to achieve longer-take, sync sound, observational films, beginning with Primary (1960).

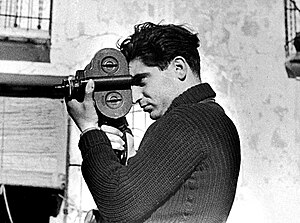

Robert Capafilm camerafilmmakingvideo productiontripodNewsreelvideo camerasprofessional video cameraselectronic news-gatheringelectronic field productionshaky cameraimage stabilizationSteadicamHistory of filmsilent filmmovie camerasAuguste and Louis LumièreCinematographWilbur WrightThomas EdisonKazimierz PrószyńskiGiuseppe de LiguoroL'InfernoThe Divine Comedycamera anglesThomas H. InceThe ItalianReginald BarkerAndré DebriemainspringAeroscopeWorld War IAbel GanceNapoléonJules KrugerZeiss-IkonNewman-Sinclairergonomics16 mm filmclockworksJ. Stuart BlacktonThe Passionate QuestSidney FranklinQuality StreetCecil B. DeMilleThe King of Kingssound filmMitchell CameraArriflex 35reflex cameraWorld War IIEclairArriflex 16STLes RaquetteursMichel BraultJean RouchDirect CinemaRaoul CoutardFrench New Wavecinéma véritédocumentary filmRichard LeacockD.A. PennebakerPrimaryÉclaircamera magazineChronicle of a SummerArriflex 16BLArriflex 16SRCahiers du CinémaBrownlow, KevinCinematic techniquesLightingBackgroundHigh-keyLens flareLow-keyRembrandtNarrationFilm scoreSound effectsShootingWide / Long / FullAmericanMediumClose-upItalianTwo shotPerspectiveOver-the-shoulderPoint-of-view (POV)ReverseSinglemultiple-camera setupCamera angleAerialHigh-angleBird's-eyeCrane shotJib shotLow-angleWorm's-eye viewDutch angleUnchained camera techniqueTiltingPanningWhip panTrackingSnorriCamWalk and talkFollowDolly zoomRackingDepth of fieldShallowZoomingEstablishing shotMaster shotB-rollFreeze-frame shotLong takeOne-shotInsertSpecial effectsPracticalAerial rigging