El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument

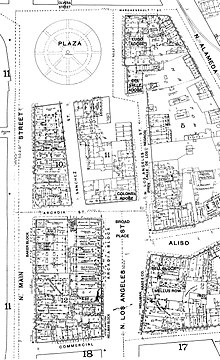

It states: "On September 4, 1781, eleven families of pobladores (44 persons including children) arrived at this place from the Gulf of California to establish a pueblo which was to become the City of Los Angeles.While at one time most of the population was north of the plaza, during the past ten years 90 per cent of the improvements have gone up in the southern half of the city.These are solid facts which it is useless to attempt to ignore by playing the ostrich acts and level-headed property holders in the northern part of the city are beginning to ask themselves seriously what is to be done to arrest or at least delay the steady march of the business section from the old to the new plaza on Sixth Street ...[6]The 44 acres (180,000 m2) surrounding the Plaza and constituting the old pueblo have been preserved as a historic park roughly bounded by Spring, Macy, Alameda and Arcadia streets, and Cesar Chavez Boulevard (formerly Sunset Boulevard).The buildings of historical significance include Nuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles Church (1822), Avila Adobe (1818) (the city's oldest surviving residence), the Olvera Street market, Pico House (1870), and the Old Plaza Fire Station (1884).[7] In addition, archaeological excavations in the Pueblo have uncovered artifacts from the long indigenous period before European contact and colonization.It was described in 1982 as "the focal point" of the state historic park, symbolizing the city's birthplace and "separating Olvera Street's touristy bustle from the Pico-Garnier block's empty buildings.The building was thereafter used as a saloon, cigar store, poolroom, "seedy hotel", Chinese market, "flop house", and drugstore.Many of the Plaza District's contributing historic buildings, including the Avila Adobe and Sepulveda House, are located on Olvera Street.Señora Gallardo’s adobe home at number 12 Bath Street was later enlarged to include by 1870 a second story and hipped roof.The décor of the room shows a practical acceptance of modern technology and contemporary fashion, with its mass-produced walnut furniture and gaslight chandelier.By contrast, the brass bed with its draperies and fancy spread, the Chinese shawl, and the well-tended shrine are representative of Señora Sepulveda’s Mexican upbringing and her strong religious beliefs.The large crucifix is on loan from Señora Sepulveda’s descendants while the bed belonged to the Avila family, who were related to her by marriage.Señora Sepulveda chose American architects George F. Costerisan and William O. Merithew to design her two-story business block for residential and commercial rental in 1887.An exception in this building is the typically Mexican breezeway which separates the Main Street stores from the dwelling rooms in the rear.When the building was constructed it appears that Señora Sepulveda herself occupied the three residential rooms located in the rear, facing Olvera Street, then an unpaved alley.Señora Sepulveda bequeathed the building on her death in 1903 to her favorite niece and goddaughter, Eloisa Martinez de Gibbs.The west façade is “penciled” in the style of the period, meaning that the bricks are painted and mortar lines are traced in white on top.The east façade on Olvera Street, although not originally painted, had previously been sandblasted, a process which destroys the outer surface of the brick, making it porous.During World War II the Sepulveda Block became a canteen for servicemen and three Olvera Street merchants were located in the building.[21] The Plaza Substation, also at 10 Olvera Street, was part of the electric streetcar system operated by the Los Angeles Railway.[23][24] The Pelanconi House was a winery producing wine from the grapes that grew in the area, possibly even inside the Avila Adobe where they grow currently.The former United Methodist Church headquarters, also built in 1926, was renamed in 1965 for Sheriff Eugene W. Biscailuz, who had helped Christine Sterling to preserve and transform Olvera Street.Here, the Coronel Adobe blocked the path north one block to the Plaza, but just slightly to the right (east) of the path of Los Angeles Street was Calle de los Negros (Spanish-language name; marked on post-1847 maps as Negro Alley or Nigger Alley), a narrow, one-block north–south street likely named after darker-skinned Mexican afromestizo and/or mulatto residents during the Spanish colonial era.[40][41].At the north end of Calle de los Negros stood the Del Valle adobe (also known as the Matthias or Matteo Sabichi house),[42][43] at the southern edge of which one could turn left and enter the plaza at its southeast corner.[44][45] The neglected dirt alley was already associated with vice by the early 1850s, when a bordello and its owner both known as La Prietita (the dark-skinned lady) were active here.Historian James Miller Guinn wrote in 1896, "in the flush days of gold mining, from 1850 to 1856, it was the wickedest street on earth...In length it did not exceed 500 feet, but in wickedness, it was unlimited.Here the ignoble red man, crazed with aguardiente, fought his battles, the swarthy Sonorian plied his stealthy dagger, and the click of the revolver mingled with the clink of gold at the gaming table when some chivalric American felt that his word of “honah” had been impugned.Some became proprietors and employees of small hand laundries and restaurants; some were farmers and wholesale produce peddlers; others ran gambling establishments; and some occupied other areas left vacant by the absence of workers in the gold rush migration to California."Around 1849, they sold the house to a "sporting fraternity", which operated a popular 24-hour gambling establishment with games including monte, faro, and poker; up to $200,000 in gold could be seen on the tables at a time.After that, still in the 1850s, it became a grocery and dry goods store (Corbett & Barker), then a storage house for iron and hard lumber for Harris Newmark Co.

U.S. National Register of Historic PlacesU.S. Historic districtLos Angeles Historic-Cultural MonumentLos Angeles, CaliforniaLos AngelesNational Register of Historic PlacesLugo AdobePueblo de Los AngelespobladoresGulf of CaliforniaCaliforniamulattoLos PobladoresCarlos IIIFelipe de NeveLos Angeles RiverTongvaYaangaHistory of Los Angeles, CaliforniaNuestra Señora La Reina de Los Ángeles ChurchAvila AdobeOlvera StreetPico HouseindigenousBrunswig BuildingLos Angeles PlazaCharles III of Spainanotherthe Californiasoriginal forty-four settlers (Los Pobladores)La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora Reina de los ÁngelesOld Plaza Firehousestatue of Father Junípero SerraChristine SterlingEastlake architectural styleDavid SiqueirosGetty Conservation InstitutePlaza SubstationLos Angeles RailwayCOVID-19 pandemicMission San GabrielEugene W. BiscailuzSentous BlockLa Placita Church (La Iglesia de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles)Vickrey-Brunswig BuildingPlaza HouseFort MoorePío PicoGovernorAlta CaliforniaItalianateCalifornia Historical LandmarkFree and Accepted MasonsMerced TheaterLA Plaza de Cultura y ArtesGarnier Block/BuildingVictorian architectureRobert Brown YoungBurgess J. ReeveChinese American MuseumCalle de los NegrosCoronel AdobecharroAntonio AguilarafromestizoYgnacio CoronelHarris NewmarkChinese massacre of 1871Los Angeles' original ChinatownHollywood Freewaytrompe-l'œilJuan Bautista de Anza National Historic TrailNational Park ServiceNational Trails SystemOld Spanish TrailOld Spanish National Historic TrailNational Park Passport StampSepúlveda HouseÁVILA ADOBEUNION STATIONOUR LADY QUEEN OF THE ANGELS CHURCHVICENTE LUGO ADOBEFelix SignoretMontgomery HouseCarrillo HouseMerced TheaterChinese MassacreFrémont'sVictorian Downtown Los AngelesList of Registered Historic Places in Los AngelesHistory of Los AngelesFort Moore Pioneer MemorialMariachi PlazaCalifornia State ParksHistorical PreservationLos Angeles TimesNational Register of Historic Places listings in Los Angeles County, California20th St.27th St.52nd Pl.Adamson HouseAdobe FloresAlex TheatreAlvarado TerraceAnderton Court ShopsAntelope Valley Indian Museum State Historic ParkArd EevinArroyo Seco ParkwayBroadwayBungalow Heaven (Pasadena)Carroll Avenue, 1300 BlockCivic Center (Pasadena)Hollywood Boulevard Commercial and Entertainment DistrictLincoln Park (Pomona)Little TokyoLower Arroyo Seco (Pasadena)Malibu Historic DistrictMenlo Ave.–W. 29th St.North University ParkOld PasadenaPark Place–Arroyo Terrace (Pasadena)Pisgah HomePoppy Peak (Pasadena)Prospect (Pasadena)Redondo Beach Original TownsiteRussian Village (Claremont)