Edward Everett

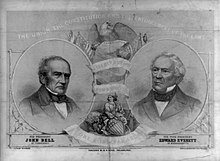

His father, a native of Dedham, Massachusetts,[2] was a descendant of early colonist Richard Everett, and his mother's family also had deep colonial roots.[8] The Reverend Buckminster died in 1812, and Everett was immediately offered the post at the Brattle Street Church on a probationary basis after his graduation, which was made permanent in November 1813."[10] Everett, over the year he served in the pulpit, came to be disenchanted with the somewhat formulaic demands of the required oratory, and with the sometimes parochial constraints the congregation placed on him.[19] Everett took up his teaching duties later in 1819, hoping to implant the scholarly methods of Germany at Harvard and bring a generally wider appreciation of German literature and culture to the United States.He wrote that Everett's voice was "of such rich tones, such precise and perfect utterance, that, although slightly nasal, it was the most mellow and beautiful and correct of all instruments of the time.[33] Brooks had made a fortune in a variety of business endeavors, including marine insurance, and would financially support Everett when he embarked on his career in politics.[28] On August 26, 1824, Everett gave an unexpectedly significant speech at Harvard's Phi Beta Kappa Society that would alter his career trajectory.Publicity for the event was dominated by the news that the Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolution, would be in attendance, and the hall was packed.He pointed out that America's situation as an expanding nation with a common language and a democratic foundation gave its people a unique and distinctive opportunity for creating truly American literature.[39] The crowd reacted with lengthy applause, and not long afterward an informal non-partisan caucus nominated Everett as its candidate for the United States House of Representatives.[45] He supported tariff legislation that protected Massachusetts' growing industrial interests, favored renewal of the charter of the Second Bank of the United States, and opposed the Indian Removal Act.[50] He attempted to justify his statements by pointing out that he rejected the slave trade and the act of kidnapping someone into slavery, but this did not mitigate the damage, and he was heavily criticized for it in the Massachusetts press.[57] Other accomplishments during Everett's tenure include the authorization of an extension of the railroad system from Worcester to the New York state line,[58] and assistance in the quieting of border tensions between Maine and the neighboring British (now Canadian) province of New Brunswick.The border issue had been simmering for some years, but tensions rose substantially in the late 1830s as both sides pushed development activity into the disputed area, and the United States refused to accept a mediation proposal made by the Dutch king.[59] Abolitionism and temperance were two issues that became more politically prominent during Everett's tenure, and both of those matters, as well as Whig indifference, would play a role in his defeat in the 1839 election.The abolitionist Liberty Party began to take shape in 1838, and the ill-timed passage of a temperance law banning the sale of less than 15 US gallons (57 L) of alcohol would drive popular support away from the Whigs in 1839.In this role Everett was instrumental in acquiring and distributing a map that vindicated the United States from accusations that it had cheated Britain out of land in the 1842 Webster–Ashburton Treaty.[66] Another major issue between the countries was the seizure of American ships by British naval forces interdicting the slave trade off the coast of Africa.Owners of ships accused but acquitted of complicity in the trade filed claims to recover their losses with the British government, and Everett, as ambassador, advanced these cases.One aspect of the slave trade interdiction proposed by Everett found its way into the treaty negotiated by Webster: the stationing of an American squadron off the coast of Africa to cooperate with the British effort.Everett in particular had to school John C. Calhoun on the diplomatic ramifications of pursuing claims after slaves mutinied aboard a ship plying the American coast and sailed it to the Bahamas.Although he had some misgivings, principally due to some of the tedious aspects of the job and difficult matter of maintaining student discipline, he accepted the offer, and entered into his duties in February 1846.[83] He was opposed to the extension of slavery in the western territories, but was concerned that the radical Free Soil Party's hardline stance would result in disunion.At President Pierce's White House socials, wrote one observer, Everett seemed as "cold-blooded and impassible, bright and lonely as the gilt weather-cock over the church in which he officiated ere he became a politician.[88] The rancor of the situation greatly upset Everett, and he submitted his resignation letter on May 12, 1854, after only a little more than one year into his six-year term, once again citing poor health.[100] Proposals were put forward that Everett serve as a roving ambassador in Europe to counter Confederate diplomatic initiatives, but these were never brought to fruition.[101] In November 1863, when Gettysburg National Cemetery was dedicated, Everett, by then widely renowned as the finest orator in the country, was invited to be the featured speaker.For his part, Everett was deeply impressed by the concise speech and wrote to Lincoln noting "I should be glad if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes.[107] At that meeting he caught a cold, which turned into pneumonia four days later, after he had testified for three hours in a civil dispute concerning property he owned in Winchester, Massachusetts.[111] Everett's name appears on the facade of the Boston Public Library's McKim Building,[112] which he helped found, serving for twelve years as president of its board.

Edward Everett (disambiguation)The ReverendUnited States Secretary of StateMillard FillmoreDaniel WebsterWilliam L. MarcyUnited States SenatorMassachusettsJohn DavisJulius RockwellPresident of Harvard UniversityJosiah QuincyJared SparksUnited States Minister to the United KingdomJohn TylerAndrew StevensonLouis McLaneGovernor of MassachusettsGeorge HullSamuel Turell ArmstrongMarcus MortonU.S. House of RepresentativesTimothy FullerSamuel HoarDorchester, MassachusettsBostonNational RepublicanConstitutional UnionNational UnionAlexander Hill EverettEdward Everett HaleLucretia Peabody HaleSusan HaleCharles HaleHenry Augustus WiseHarvard UniversityUniversity of GöttingenUnitarianU.S. representativeU.S. senatorminister to Great Britainits presidentCivil WarGettysburg National CemeteryAbraham LincolnGettysburg AddressBrattle Street Churchancient Greek literatureUnited States Congressstate Board of EducationAmerican Philosophical Society1839 electionVice PresidentConstitutional Union Party1864 electionDedham, MassachusettsRichard EverettNew South ChurchDanielSarah Preston HaleBoston Latin SchoolPhillips Exeter AcademyHarvard CollegevaledictorianPorcellian ClubHasty PuddingJoseph Stevens BuckminsterJohn Thornton KirklandGeorge TicknorWashington, D.C.Federalist PartyGreek literatureAmerican Antiquarian SocietyLondonGöttingenthe universityFrenchGermanItalianRoman lawGreek artHanoverWeimarDresdenBerlinConstantinopleBlack SeaPrussianWilhelm von HumboldtPrussian education systemWilliam WilberforceabolitionistRalph Waldo EmersondaguerreotypePhilipp Karl ButtmannSpeaker of U.S. House of RepresentativesRobert Charles WinthropCharles Francis AdamsAmerican Academy of Arts and SciencesNorth American ReviewGerman languageJohann Wolfgang von GoetheUnited States Capitoltheir struggle for independenceOttoman EmpireNational GalleryAthensAmerican RevolutionConcord, MassachusettsLexington, MassachusettsPeter Chardon Brooksmarine insuranceJohn Quincy AdamsCharles Francis Adams, Sr.William EverettPhi Beta Kappa SocietyMarquis de LafayetteUnited States House of RepresentativesBoard of OverseersDemocratic-Republican PartyHenry ClayNational Systeminternal improvementsWhig PartyWhite HouseSecond Bank of the United States