Price elasticity of demand

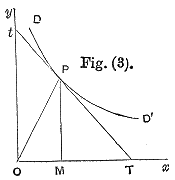

[7] Since the price elasticity of demand is negative for the vast majority of goods and services (unlike most other elasticities, which take both positive and negative values depending on the good), economists often leave off the word "negative" or the minus sign and refer to the price elasticity of demand as a positive value (i.e., in absolute value terms).If demand is unitary elastic, the quantity falls by exactly the percentage that the price rises.[8][9] If a 1% rise in the price of gasoline causes a 0.5% fall in the quantity of cars demanded, the cross-price elasticity isAs the size of the price change gets bigger, the elasticity definition becomes less reliable for a combination of two reasons.First, a good's elasticity is not necessarily constant; it varies at different points along the demand curve because a 1% change in price has a quantity effect that may depend on whether the initial price is high or low.For example, suppose that when the price rises from $10 to $16, the quantity falls from 100 units to 80.Loosely speaking, this gives an "average" elasticity for the section of the actual demand curve—i.e., the arc of the curve—between the two points.As a result, this measure is known as the arc elasticity, in this case with respect to the price of the good.The arc elasticity is defined mathematically as:[16][17][18] This method for computing the price elasticity is also known as the "midpoints formula", because the average price and average quantity are the coordinates of the midpoint of the straight line between the two given points.However, because this formula implicitly assumes the section of the demand curve between those points is linear, the greater the curvature of the actual demand curve is over that range, the worse this approximation of its elasticity will be.One way to avoid the accuracy problem described above is to minimize the difference between the starting and ending prices and quantities.This is the approach taken in the definition of point elasticity, which uses differential calculus to calculate the elasticity for an infinitesimal change in price and quantity at any given point on the demand curve:[20] In other words, it is equal to the absolute value of the first derivative of quantity with respect to price[24] He reasons this since "the only universal law as to a person's desire for a commodity is that it diminishes ... but this diminution may be slow or rapid.If it is slow... a small fall in price will cause a comparatively large increase in his purchases."[25] Mathematically, the Marshallian PED was based on a point-price definition, using differential calculus to calculate elasticities.[26] The overriding factor in determining the elasticity is the willingness and ability of consumers after a price change to postpone immediate consumption decisions concerning the good and to search for substitutes ("wait and look").[27] A number of factors can thus affect the elasticity of demand for a good:[28] When measuring Marshallian demand—the demand curve holding nominal, rather than real, income constant—the percentage of income a customer spends on a certain good also affects the elasticity.In introductory microeconomics, the distinction between Marshallian and Hicksian (real-value) demand is often ignored, assuming that any particular good will be a small part of the customer's budget, but for large or frequent purchases (e.g. food or transportation) the income effect can become substantial or even dominate the price effect (as for Giffen goods).[28][29][34] When the goods represent only a negligible portion of the budget, the income effect is insignificant and does not contribute substantially to elasticity.But in determining whether to increase or decrease prices, a firm needs to know what the net effect will be.As a result, the relationship between elasticity and revenue can be described for any good:[38][39] Hence, as the accompanying diagram shows, total revenue is maximized at the combination of price and quantity demanded where the elasticity of demand is unitary.Hence, suppliers can increase the price by the full amount of the tax, and the consumer would end up paying the entirety.In the opposite case, when demand is perfectly elastic, by definition consumers have an infinite ability to switch to alternatives if the price increases, so they would stop buying the good or service in question completely—quantity demanded would fall to zero.As a result, firms cannot pass on any part of the tax by raising prices, so they would be forced to pay all of it themselves.More generally, then, the higher the elasticity of demand compared to PES, the heavier the burden on producers; conversely, the more inelastic the demand compared to supply, the heavier the burden on consumers.When PED, PES or both are inelastic, the deadweight loss is lower than a comparable scenario with higher elasticity.If the definition of price elasticity is extended to yield a quadratic relationship between demand units (Various research methods are used to calculate the price elasticities in real life, including analysis of historic sales data, both public and private, and use of present-day surveys of customers' preferences to build up test markets capable of modelling such changes.[44] Alternatively, conjoint analysis (a ranking of users' preferences which can then be statistically analysed) may be used.This approach has been empirically validated using bundles of goods (e.g. food, healthcare, education, recreation, etc.).

Income elasticity of demandCross elasticity of demandWealth elasticity of demandPrice elasticity of supplylaw of demandelasticitiesVeblenGiffen goodsincidence (or "burden") of a taxtest marketsconjoint analysisGiffenabsolute valuecomplementarysubstitute goodcross-price elasticity of demanddemand curvecommon misconceptionarc elasticitymidpoint methoddifferential calculusdemand functionAlfred MarshallPrinciples of Economicssubstitutesinsulincarpoolingfuel economyconsumer durablesattachment to a certain brandMarshallian demandnominal, rather than real, incomemicroeconomicsHicksian (real-value) demandincome effectmarginal revenueTotal revenue testfiat currencytax incidenceProfit maximizationAlcoholic beveragesbroiler chickenspediatricCoca-ColaMountain DewSupply and demandHarperCollinsBibcodede Rassenfosse, GaétanMas-Colell, AndreuAggregationBudget setConsumer choiceConvexitynon-convexityAverageMarginalOpportunityImplicitSocialTransactionCost–benefit analysisDeadweight lossDistributionEconomies of scaleEconomies of scopeElasticityEquilibriumGeneralExchangeExternalityGoods and servicesServiceHouseholdIncome–consumption curveInformationIndifference curveIntertemporal choiceMarketMarket failureMarket structureCompetitionMonopolisticPerfectDuopolyMonopolyBilateralMonopsonyOligopolyOligopsonyPareto efficiencyPreferencesPrice controlsPrice ceilingPrice floorPrice discriminationPrice signalPrice systemPricingProductionProfitPublic goodsRationingReturns to scaleRisk aversionScarcityShortageExcess supplySubstitution effectSurplusSocial choiceDemandSupplyLaw of supplyUncertaintyUtilityExpectedBehavioralBusinessComputationalDevelopmentStatistical decision theoryEconometricsEngineering economicsCivil engineering economicsEvolutionary