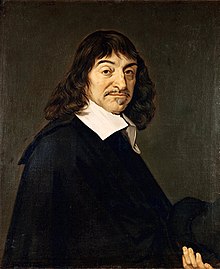

Cogito, ergo sum

[b] Descartes's statement became a fundamental element of Western philosophy, as it purported to provide a certain foundation for knowledge in the face of radical doubt.The phrase first appeared (in French) in Descartes's 1637 Discourse on the Method in the first paragraph of its fourth part: Ainsi, à cause que nos sens nous trompent quelquefois, je voulus supposer qu'il n'y avait aucune chose qui fût telle qu'ils nous la font imaginer; Et parce qu'il y a des hommes qui se méprennent en raisonnant, même touchant les plus simples matières de Géométrie, et y font des Paralogismes, jugeant que j'étais sujet à faillir autant qu'aucun autre, je rejetai comme fausses toutes les raisons que j'avais prises auparavant pour Démonstrations; Et enfin, considérant que toutes les mêmes pensées que nous avons étant éveillés nous peuvent aussi venir quand nous dormons, sans qu'il y en ait aucune raison pour lors qui soit vraie, je me résolus de feindre que toutes les choses qui m'étaient jamais entrées en l'esprit n'étaient non plus vraies que les illusions de mes songes.[i][j] In Response to an Objection from Marin Mersenne, he wrote "cogito, ergo sum” in an extended form and, again, prefaced with ‘ego’: Cum advertimus nos esse res cogitantes, prima quædam notio est quæ ex nullo syllogismo concluditur; neque etiam cum quis dicit ‘ego cogito, ergo sum, sive existo,’[h] existentiam ex cogitatione per syllogismum deducit, sed tanquam rem per se notam simplici mentis intuitu agnoscit.In 1644, Descartes published (in Latin) his Principles of Philosophy where the phrase "ego cogito, ergo sum" appears in Part 1, article 7:Sic autem rejicientes illa omnia, de quibus aliquo modo possumus dubitare, ac etiam, falsa esse fingentes, facilè quidem, supponimus nullum esse Deum, nullum coelum, nulla corpora; nosque etiam ipsos, non habere manus, nec pedes, nec denique ullum corpus, non autem ideò nos qui talia cogitamus nihil esse: repugnat enim ut putemus id quod cogitat eo ipso tempore quo cogitat non existere.Ac proinde haec cognitio, ego cogito, ergo sum,[c] est omnium prima & certissima, quae cuilibet ordine philosophanti occurrat.[m] Descartes's margin note for the above paragraph is: Non posse à nobis dubitari, quin existamus dum dubitamus; atque hoc esse primum, quod ordine philosophando cognoscimus.1647,[17] originally in French with the title La Recherche de la Vérité par La Lumiere Naturale (The Search for Truth by Natural Light)[3] and later in Latin with the title Inquisitio Veritatis per Lumen Naturale,[18] provides his only known phrasing of the cogito as cogito, ergo sum and admits that his insight is also expressible as dubito, ergo sum:[4] ... [S]entio, oportere, ut quid dubitatio, quid cogitatio, quid exsistentia sit antè sciamus, quàm de veritate hujus ratiocinii: dubito, ergo sum, vel, quod idem est, cogito, ergo sum[c] : plane simus persuasi.A further expansion, dubito, ergo cogito, ergo sum—res cogitans ("…—a thinking thing") extends the cogito with Descartes's statement in the subsequent Meditation, "Ego sum res cogitans, id est dubitans, affirmans, negans, pauca intelligens, multa ignorans, volens, nolens, imaginans etiam et sentiens…" ("I am a thinking [conscious] thing, that is, a being who doubts, affirms, denies, knows a few objects, and is ignorant of many,-- who loves, hates,[q] wills, refuses, who imagines likewise, and perceives")."[28][s] While the Latin cōgitō may be translated rather easily as "I think/ponder/visualize", je pense does not indicate whether the verb form corresponds to the English simple present or progressive aspect.[31] Following John Lyons (1982),[32] Vladimir Žegarac notes, "The temptation to use the simple present is said to arise from the lack of progressive forms in Latin and French, and from a misinterpretation of the meaning of cogito as habitual or generic" (cf.'"[42] Descartes wrote this phrase as such only once, in the posthumously published lesser-known work noted above, The Search for Truth by Natural Light."[47] At the beginning of the second meditation, having reached what he considers to be the ultimate level of doubt—his argument from the existence of a deceiving god—Descartes examines his beliefs to see if any have survived the doubt.Descartes does not use this first certainty, the cogito, as a foundation upon which to build further knowledge; rather, it is the firm ground upon which he can stand as he works to discover further truths.As a consequence of this demonstration, Descartes considers science and mathematics to be justified to the extent that their proposals are established on a similarly immediate clarity, distinctiveness, and self-evidence that presents itself to the mind.The originality of Descartes's thinking, therefore, is not so much in expressing the cogito—a feat accomplished by other predecessors, as we shall see—but on using the cogito as demonstrating the most fundamental epistemological principle, that science and mathematics are justified by relying on clarity, distinctiveness, and self-evidence.[54] Spanish philosopher Gómez Pereira in his 1554 work Antoniana Margarita, wrote "nosco me aliquid noscere, & quidquid noscit, est, ergo ego sum" ('I know that I know something, anyone who knows is, therefore I am').[55][56] In Descartes, The Project of Pure Enquiry, English philosopher Bernard Williams provides a history and full evaluation of this issue.[57] The first to raise the "I" problem was Pierre Gassendi, who in his Disquisitio Metaphysica,[58] as noted by Saul Fisher, "points out that recognition that one has a set of thoughts does not imply that one is a particular thinker or another.The obvious problem is that, through introspection, or our experience of consciousness, we have no way of moving to conclude the existence of any third-personal fact, to conceive of which would require something above and beyond just the purely subjective contents of the mind.In order to formulate a more adequate cogito, Macmurray proposes the substitution of "I do" for "I think," ultimately leading to a belief in God as an agent to whom all persons stand in relation."[66] In the episode "Work Experience" of The Office, David Brent says, "We are the most efficient branch, cogito ergo sum, we'll be fine.

I Think, Therefore I AmTherefore I Am (song)René DescartesDiscourse on the MethodCartesianismRationalismFoundationalismMechanismDoubt and certaintyDream argumentEvil demonTrademark argumentCausal adequacy principleMind–body dichotomyAnalytic geometryCoordinate systemCartesian circleFoliumRule of signsCartesian diverBalloonist theoryWax argumentRes cogitansRes extensaRules for the Direction of the MindThe Search for TruthThe WorldLa GéométrieMeditations on First PhilosophyPrinciples of PhilosophyPassions of the SoulChristina, Queen of SwedenNicolas MalebrancheBaruch SpinozaGottfried Wilhelm LeibnizFrancine Descartesfirst principleFrenchdictummargin noteexistenceThe Search for Truth by Natural LightAntoine Léonard ThomasWestern philosophycertainfoundation for knowledgeradical doubtthinking entityPierre GassendiMarin Mersennesimple presentprogressive aspectJohn Lyonsgnomic aspectAnn BanfieldSimon BlackburnCharles Porterfield KrauthClassical LatinPrincipia PhilosophiaeKrauthnecessarily trueGeorge Henry Lewesinstantiation principleArchimedesÉtienne GilsonPrincipia philosophiae cartesianaesubstanceontologicalParmenidesAristotleNicomachean EthicssyllogismbeingsAugustine of HippoDe Civitate DeiIsaac BeeckmanAvicennaFloating Manthought experimentself-awarenessself-consciousnessAdi ShankaraGómez PereiraBernard WilliamsGeorg LichtenbergFriedrich Nietzscheimpersonal subjectSøren KierkegaardtautologyConcluding Unscientific Postscriptthird-personobjectiveintrospectionconsciousnessCartesian subjectivityMartin HeideggerDaseinJohn Macmurrayshort storyI Have No Mouth, and I Must ScreamHarlan EllisonsentienceJapanese animatedErgo Proxycomputer virusrobotsconsciousemotionsMonty PythonBruces' Philosophers SongDescarte'sWork ExperienceThe OfficeDavid BrentphilosopherCartesian doubtApperceptionAcademic skepticismBe, and it isBrain in a vatI Am that I AmTat Tvam AsiThe Animal That Therefore I AmVertiginous questionMiddle FrenchModern French