Christianization

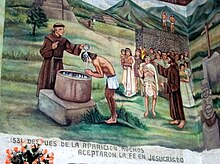

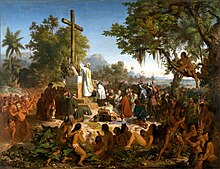

[39] Historian Philip Schaff has written that sprinkling, or pouring of water on the head of a sick or dying person, where immersion was impractical, was also practiced in ancient times and up through the twelfth century.[55][56] While many new subjects appear for the first time in the Christian catacombs - i.e. the Good Shepherd, Baptism, and the Eucharistic meal – the Orant figures (women praying with upraised hands) probably came directly from pagan art.According to historian Hans Kloft, that was because the Eleusinian Mysteries, Demeter's cult, ended in the 4th century, and the Greek rural population gradually transferred her rites and roles onto the Christian saint.For example, Christian historians recorded that Hadrian (2nd century), when in the military colony of Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), had constructed a temple to Aphrodite on the site of the crucifixion of Jesus on Golgotha hill in order to suppress veneration there.[101] Professor of Byzantine history Helen Saradi-Mendelovici writes that this process implies appreciation of antique art and a conscious desire to find a way to include it in Christian culture.[115] Ancient sites were viewed with veneration, and were excluded or included for Christian use based largely on diverse local feeling about their nature, character, ethos and even location.The Franks cut down the Irminsul, looted the accumulated sacrificial treasures (which the King distributed among his men), and torched the entire grove... Charlemagne ordered a Frankish fortress to be erected at the Eresburg".[129] Large numbers of pre-Christian names survive into the present day, and Sørensen says this demonstrates the process of Christianization in Denmark was peaceful and gradual and did not include the complete eradication of the old cultic associations.[180] Still, Bradbury notes that the complete disappearance of public sacrifice by the mid-fourth century "in many towns and cities must be attributed to the atmosphere created by imperial and episcopal hostility".In response, the Frankish King "enacted a variety of draconian measures" beginning with the massacre at Verden in 782 when he ordered the decapitation of 4500 Saxon prisoners offering them baptism as an alternative to death.[213] These events were followed by the severe legislation of the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae in 785 which prescribes death to those that are disloyal to the king, harm Christian churches or its ministers, or practice pagan burial rites.[224] Relying largely on recent archaeological developments, Lorcan Harney has reported to the Royal Academy that the missionaries and traders who came to Ireland in the fifth to sixth centuries were not backed by any military force.As M. L. Chaumont established in 1969, the latter, with the help of Gregory the Illuminator, adopted the Christian faith at the state level in June 311, two months after the publication of the Edict of Sardica "On Tolerance" by Emperor Galerius (293–311).[262] According to medieval Georgian Chronicles, Christianization began with Andrew the Apostle and culminated in the evangelization of Iberia through the efforts of a captive woman known in Iberian tradition as Saint Nino in the fourth century.[268] With the end of persecution in 312, churches, baptistries, hospitals and episcopal palaces were erected in most major towns, and many landed aristocracy embraced the faith and converted sections of their villas into chapels.[32][32][note 11] In the Christianization process of Bohemia, Moravia and Slovakia territories, the two Byzantine missionary brothers Saints Constantine-Cyril and Methodius played the key roles beginning in 863.[295][296] The conversion of Gyula at Constantinople and the missionary work of Bishop Hierotheus are depicted as leading directly to the court of St. Stephen, the first Hungarian king, a Christian in a still mostly pagan country.[314] From before the days of Charlemagne (747–814), the fierce pagan tribes east of the Baltic Sea lived on the physical frontiers of Christendom in what has today become Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the Kaliningrad oblast (Prussia).[326][327] In some cases, voluntary conversion of the local aristocracy—usually followed by the populace, under this influence—was recognized, and stayed the hand of war; in others, naked ambition and greed for material wealth resulted in military actions against ostensibly already-converted peoples.Medieval historian Aiden Lilienfeld says "In 1226, however, the Duke of Mazovia ... granted the Order territory in eastern Prussia in exchange for help in subjugating pagan Baltic peoples".[336] Christian clergy translated religious texts into local vernacular language which introduced literacy to all members of the princely dynasty, including women and the general populace.[341] The centuries long military struggle to reclaim the peninsula from Muslim rule, called the Reconquista, took place until the Christian Kingdoms, that would later become Spain and Portugal, reconquered the Moorish Al-Ándalus in 1492.In 1478, they established the Spanish Inquisition, telling the Pope it was needed to find heretics - specifically Jews pretending to be Christian so they could spy for Moslems who wanted their territory back.[347] Following the geographic discoveries of the 1400s and 1500s, increasing population and inflation led the emerging nation-states of Portugal, Spain, and France, the Dutch Republic, and England to explore, conquer, colonize and exploit the newly discovered territories.[352] He goes on to explain this is because, "Despite their role as allies of the empire, missions also developed the vernacular that inspired sentiments of national identity and thus undercut Christianity's identification with colonial rule".This common theory of the time asserts that history shows the normal progression of society is toward constant betterment; that humans could therefore eventually be perfected; that primitive nations could be forced to become modern states wherein that would happen.[388] Historian Jacob Schacter says these missions were universally Protestant, were based on belief in the traditional duty to "teach all nations", the sense of "obligation to extend the benefits of Christianity to heathen lands" (just as Europe itself had been "civilized" centuries before), and a "fervent pity" for those who had never heard the gospel.[407] Mark Boyle writes that: Christianity's historical alignment with the Western project and [the overlapping] histories of colonialism and imperialism raises questions about its capacity to serve as a progressive force in global affairs today.[404] Joseph Tse-Hei Lee observes that, historically, Christianity has long had a tendency to flourish in areas where there is suffering, dislocation and warfare, and that this is evident in its modern development in China.[149] According to Raymond Van Dam, "an approach which emphasizes conflict flounders as a means for explaining both the initial attractions of a new cult like Christianity, as well as, more importantly, its persistence".

History of religionsFounding figuresChristianityMuhammadAbrahamJudaismSiddhartha GautamaBuddhismGuru NanakSikhismMahaviraJainismZoroasterZoroastrianismHamza ibn AliDruzismTaoismConfuciusConfucianismBaháʼu'lláhBaháʼí FaithReligious studiesAnthropologyComparative religionNeurotheologyGod geneOriginsPsychologyPrehistoricAncient Near EastAncient EgyptMesopotamiaSemiticIndo-EuropeanHistorical Vedic religionAncient Greek religionCelticGermanicAxial AgeVedantaŚramaṇaDharmaHellenismMonismDualismMonotheismIslamizationRenaissanceReformationAge of ReasonNew religious movementsGreat AwakeningFundamentalismNew AgePostmodernismAbrahamicBahá'í FaithHinduismEast AsianNeopaganChristNativityBaptismMinistryCrucifixionResurrectionAscensionOld TestamentNew TestamentGospelChurchNew CovenantTheologyTrinityFatherHoly SpiritApologeticsChristologyHistory of theologyMissionSalvationUniversalismHistoryTraditionApostlesEarly ChristianityChurch FathersConstantineCouncilsAugustineIgnatiusEast–West SchismCrusadesAquinasLutherDenominations(full list)NiceneCatholicEasternOld CatholicPalmarian CatholicIndependent CatholicSedevacantismEastern OrthodoxOriental OrthodoxChurch of the EastProtestantAdventistAnabaptistAnglicanBaptistFree EvangelicalLutheranMethodistMoravian [Hussite]PentecostalPlymouth BrethrenQuakerReformedUnited ProtestantWaldensianNondenominational ChristianityRestorationistChristadelphiansIglesia ni Cristo