Cheshire Lines Committee

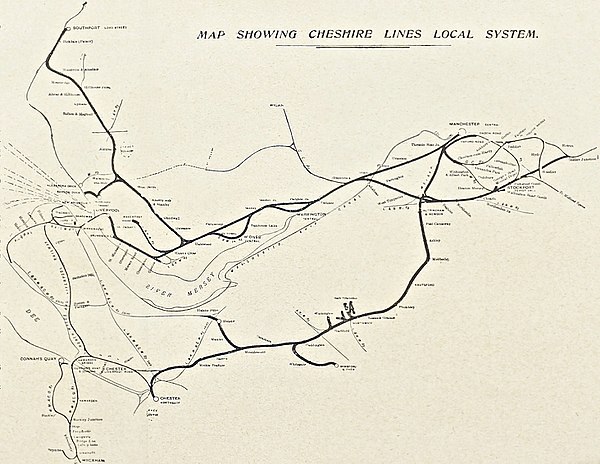

[3] The CLC operated in an area which included the rapidly growing major cities of Manchester and Liverpool, the developing Lancashire coal fields and the growth of the Mersey's seaborne trade.[note 2][17][18] This act had not, however, formally set up a separate legal body, providing instead for the two companies to manage and work the four railways through their existing structures.[20] Included within this act were running powers between Garston Dock and Timperley Junction using the lines of the LNWR through Widnes, Warrington and Lymm.[17] Liverpool Brunswick station was inconveniently situated near the Southern docks, a good distance from the city centre.[24] The MS&LR's Godley and Woodley Branch Railway was transferred to the CLC by the Cheshire Lines Act 1866 (29 & 30 Vict.[30] He had a point, as the lines were being used by three companies and had several curves that needed careful, and therefore slow, negotiation; there were 95 level-crossings and 60 or more signals in each direction.The building was so large, about 300 by 500 feet (91 m × 152 m), it was long enough to write the owners names in full Great Northern, Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire and Midland Railways.[41][42] The second diversion was between Glazebrook and West Timperley where both intermediate stations, Cadishead and Partington, were rebuilt on raised lines either side of the ship canal.[note 11][44] This was a natural extension of the CLC network and indeed authorised, albeit by a different company, what the West Cheshire Railway had applied, and failed, to do in 1861.It brought access to the county town of Chester, an important tourist centre and gateway to North Wales to the expanding network.[46] The junction at Mickle Trafford was made in 1875 to enable traffic between the CLC and Chester General but it was not used due to a dispute.[48] The CLC ran five trains in each direction daily between Manchester Oxford Road which was a MSJ&AR station and Chester Northgate.c. lvii), to build a new line 1 mile 20 chains (2.0 km) long from Cornbrook into Manchester, with all proper stations, approaches, works and conveniences connected therewith, terminating on the southern side of Windmill Street.[54] This station was a modest affair, with two platforms and two intermediate tracks, but it enabled the CLC to introduce an improved hourly express service to Liverpool taking 45 minutes which attracted passengers.[50][55] Even before the temporary Free Trade Hall station opened, the CLC had been authorised by the Cheshire Lines Act 1875 (38 & 39 Vict.[note 13] This station had two storeys, goods below and passengers above; it had eight platforms, later increased to nine, six of which were covered by an impressive 210 feet (64 m) single span roof, the other two were protected by an awning on the side of the shed.[61] The GNR worked goods trains into it from Colwick, using running powers over the Midland from Codnor Park Junction.[note 15][67] A condition of the joint railway was equal funding of the capital to build the line; the MS&LR was not forthcoming with their share and the Midland then petitioned for the undertaking to be transferred to its sole ownership, which was accepted.Despite improvements made during the 1870s and 1880s and connections with adjacent docks from 1884, the CLC was not able to compete with other railways in the area for the large freight market.[79][80] This connection at Aintree provided an additional route onto the CLC for Midland Railway traffic, which had access from the north via Colne and Preston.[note 1][17][18] The management committee (still at this time just MS&LR and GNR) became direct owners and operators of railways, by the Cheshire Lines Transfer Act 1865 (28 & 29 Vict.There followed another interim period, with Charlton and Blundell and the Indoor Assistant, William Oates, running the committee until a new manager, John Edward Charnley, was appointed in August 1911.[92] The CLC continued under this management arrangement through the Second World War until the railways were nationalised under the Transport Act 1947 (10 & 11 Geo.Its motive power was provided by the parent companies which, in practice, was the MS&LR, as it had a comparatively close locomotive works at Gorton in east Manchester.[93] Arbitration concluded that there was no viable alternative and the MS&LR (later the GCR/LNER) would provide locomotives for CLC needs, albeit at a slightly reduced rate.The CLC's only contribution to motive power was the introduction of four Sentinel-Cammell steam railcars that were introduced in 1929; they worked all over the network until were withdrawn in 1941 and scrapped in 1944.In 1904, the Gloucester Railway Carriage and Wagon Company supplied some eight-wheel bogie coaches to the CLC designed by John G. Robinson of the GCR.New articulated stock was introduced in 1937, designed by Nigel Gresley and with a teak finish, for the Liverpool to Manchester service; they were in two trains each of four twins.[115] Similarly, the CLC had its own fleet of wagons, which were painted a pale lead grey for the bodywork, with black running gear and white lettering.[124] Liverpool Central high-level has been demolished with local services on the former CLC line, operated by Merseyrail, running through an underground station on the same site.

LancashireCheshireStockport and Woodley Junction RailwayCheshire Midland RailwayStockport, Timperley and Altrincham Junction RailwayWest Cheshire RailwayGarston and Liverpool RailwayBritish RailwaysTrack gaugestandard gaugejoint railwayBig FourgroupingLiverpoolManchesterStockportWarringtonWidnesNorthwichWinsfordKnutsfordChesterSouthportManchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire RailwayGreat Northern RailwayLondon and North Western RailwayManchester London RoadLondon Kings Cross21 & 22 Vict.Cheshire MidlandStockport and Woodley JunctionGarston & LiverpoolStockport, Timperley & Altrincham JunctionWest CheshireParliament of the United KingdomCitation26 & 27 Vict.Garston and Liverpool Railway Act 186124 & 25 Vict.Garston DockManchester, South Junction and Altrincham RailwayCentral StationLiverpool Central Station Railway Act 186427 & 28 Vict.Midland RailwayLong title28 & 29 Vict.Royal assent29 & 30 Vict.GodleyWoodley30 & 31 Vict.Manchester Oxford RoadMSJ&AROld TraffordArdwickTimperleyGuide BridgeGodley JunctionPenistoneSheffieldRomileyMarpleStockport PortwoodStockport Tiviot DaleCheadleNorthendenBaguleyAltrinchamBroadheathBowdonAshleyMobberleyCressingtonPlumbleyMersey RoadLostock GralamOtterspoolSt MichaelsLiverpool BrunswickSandbachHartford and GreenbankCuddingtonDelamereWhitegateMouldsworthWinsford and OverHelsby and AlvanleyBirkenhead RailwayBirkenhead Joint RailwayEdward WatkinLancashire and Yorkshire RailwayGreat Eastern RailwayManchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (Extension to Liverpool) Act 1865Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (New Lines) Act 1866PadgateSankeyWarrington CentralManchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (Liverpool Extension) Act 1866Liverpool Central stationWidnes loop lineFarnworthWidnes CentralHough GreenManchester Ship CanalstationGlazebrookWest TimperleyCadisheadPartingtonChester and West Cheshire Junction RailwayChester and West Cheshire Junction Railway CompanyChester NorthgateTarvin & BarrowMickle TraffordChester General35 & 36 Vict.38 & 39 Vict.Manchester Centralgoods warehouseDeansgateManchester South District RailwayManchester South District Railway Act 187336 & 37 Vict.Chorlton-cum-HardyWithington