Battle of the Eurymedon

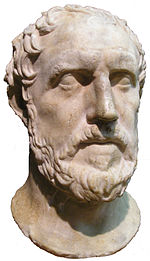

The Delian League had been formed between Athens and many of the city-states of the Aegean to continue the war with Persia, which had begun with the first and second Persian invasions of Greece (492–490 and 480–479 BCE, respectively).In the aftermath of the Battles of Plataea and Mycale, which had ended the second invasion, the Greek Allies had taken the offensive, besieging the cities of Sestos and Byzantium.Hearing of the Persian preparations, the Athenian general Cimon took 200 triremes and sailed to Phaselis in Pamphylia, which eventually agreed to join the Delian League.However, the Delian League do not appear to have pressed home their advantage, probably because of other events in the Greek world that required their attention.[1][2] The richest source for the period, and also the most contemporary with it, is the History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, which is generally considered by modern historians to be a reliable primary account.[3][4][5] Thucydides only mentions the pentekontaetia period in a digression, discussing the growth of Athenian power in the run up to the Peloponnesian War.[6][7] Nevertheless, historians have used Thucydides' account to construct a rough chronology for the period, as a basis for interpreting archaeological records and other writers.[8] In his biographies, Plutarch explicitly draws on many ancient histories that have not survived, preserving details of the period that Thucydides's account omits.The only other major extant source for the period is Bibliotheca historica, a universal history written in the 1st century BC by Diodorus Siculus.Much of Diodorus's description of this period seems to be derived from the much earlier Greek historian Ephorus, who also wrote a universal history which is now lost.[6] Thucydides also narrates Eurymedon after the revolt of Naxos, which the same author in turn associates with the flight of Themistocles to Persia and the death of Persian king Xerxes in 465, suggesting that the battle was fought no earlier than 466.Many historians hold that this was done because a great victory involving all generals had been achieved, and that the most likely candidate for such is the battle of Eurymedon, which will have taken place in the previous year, 469.[15][23] The Greco-Persian Wars had their roots in the conquest of the Greek cities of Asia Minor, and in particular Ionia, by the Persian Empire of Cyrus the Great shortly after 550 BC.[27] The Greek states of Athens and Eretria allowed themselves to be drawn into this conflict by Aristagoras, and during their only campaigning season (498 BC) they contributed to the capture and burning of the Persian regional capital of Sardis.[22] Cawkwell outlines the Persian strategic problems: "Persia was a land power which used its naval forces in close conjunction with its armies, not free ranging in enemy waters."[51] The nature of naval warfare in the Ancient world, dependent as it was on large teams of rowers, meant that ships would have to make landfall every few days to resupply with food and water.[52] This severely limited the range of an ancient fleet, and essentially meant that navies could only operate in the vicinity of secure naval bases.By capturing Phaselis, the furthest east Greek city in Asia Minor (and just to the west of the Eurymedon), he effectively blocked the Persian campaign before it had begun, denying them the first naval base they needed to control.[44] Although Thucydides's account is generally to be favoured, there may an element of truth in Plutarch's assertion that the Persians were awaiting further reinforcements; this would explain why Cimon was able to launch a pre-emptive assault on them.Despite the weariness of his troops after this first battle, Cimon, seeing "that his men were exalted by the impetus and pride of their victory, and eager to come to close quarters with the Barbarians", landed the marines and proceeded to attack the Persian army.[64] The alternative suggested by Plutarch is that the Persian king acted as if he had made a humiliating peace with the Greeks, because he was so fearful of engaging in battle with them again.[15] If the later date of 466 BC for the Eurymedon campaign is accepted, this might be because the revolt in Thasos meant that resources were diverted away from Asia Minor to prevent the Thasians seceding from the League.[62] The Persian fleet was effectively absent from the Aegean until 451 BC, and Greek ships were able to ply the coasts of Asia Minor with impunity.

Roman-Syrian WarBattle of the Eurymedon (190 BC)Wars of the Delian LeagueEurymedon RiverKöprüçay RiverAntalyaTurkeyDelian LeagueAchaemenid EmpireTithraustesPherendatisWars of the Delian LeagueThasosAthensPersian EmpireXerxes IKöprüçayPamphyliaAsia MinorGreco-Persian WarsAegeansecondPlataeaMycalebesiegingByzantiumtriremesPhaselissecond Persian invasionPeloponnesian WarpentekontaetiaHistory of the Peloponnesian WarThucydidesPlutarchParallel LivesAristidesthat have not survivedBibliotheca historicauniversal historyDiodorus SiculusEphorusCharles Henry OldfatherinscriptionsThemistoclesXerxesCyrus the GreattyrantMiletusAristagorasexpeditionAeolisIonian RevoltEretriaSardisDarius the Greatfirst invasionThraceMacedonBattle of Marathonsecond invasionThermopylaeArtemisiumPeloponnesusBattle of SalamisBattle of PlataeaBattle of MycaleChersonesosIstanbulPausaniasPontusAlexander the GreatCnidustalentstriremeBattle of LadehopliteEurymedon vaseHerodotusXenophonWayback MachinePhotiosCawkwell, GeorgeOxford University PressHarvard University PressDoubledayWorld History EncyclopediaFamily treeTimelineHistory of democracyAchaemenid Persian Lion RhytonOxus TreasureAchaemenid coinageApadana hoardDanakeArchitecturePersepolisApadanaGate of All NationsTacharaPalace of Darius in SusaTomb of CyrusPersian columnNaqsh-e RostamKa'ba-ye ZartoshtMausoleum at HalicarnassusTombs at XanthosHarpy TombNereid MonumentTomb of PayavaAchaemenid musicOld Persian cuneiformOld PersianBehistun InscriptionXerxes I's inscription at VanGanjnamehCyrus CylinderPersian RevoltBattle of HyrbaBattle of the Persian BorderBattle of PteriaBattle of ThymbraSiege of Sardis (547 BC)Battle of OpisConquest of the Indus ValleyFirst conquest of EgyptScythian campaign of Darius I