Utamaro

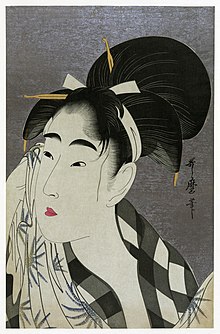

In 1804 he was arrested and manacled for fifty days for making illegal prints depicting the 16th-century military ruler Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and died two years later.The names of his parents are not known; it has been suggested his father may have been a Yoshiwara teahouse owner, or Toriyama Sekien,[9] an artist who tutored him[11] and who wrote of Utamaro playing in his garden as a child.[11] Sekien, although trained in the upper-class Kanō school of Japanese painting, had become in middle age a practitioner of ukiyo-e and his art was aimed at the townspeople in Edo.His next known works appear in 1775 under the name Kitagawa Toyoaki,[e][14]—the cover to a kabuki playbook entitled Forty-eight Famous Love Scenes[f] which was distributed at the Edo playhouse Nakamura-za.[13] As Toyoaki, Utamaro continued as an illustrator of popular literature for the rest of the decade, and occasionally produced single-sheet yakusha-e portraits of kabuki actors.Per custom, he distributed a specially made print for the occasion, in which, before a screen bearing the names of his guests, is a self-portrait of Utamaro making a deep bow.[16] Utamaro's first work for Tsutaya appeared in a publication dated as 1783: The Fantastic Travels of a Playboy in the Land of Giants,[g] a kibyōshi picture book created in collaboration with his friend Shimizu Enjū, a writer.Evidence of his prints for the next few years is sporadic, as he mostly produced illustrations for books of kyōka ("crazy verse"), a parody of the classical waka form.When artists and writers put out prints and books based on the Ehon Taikōki in the disparaged ukiyo-e style, it attracted reprisals from the government.In probably the most famous case of censorship of the Edo period,[24] Utamaro was imprisoned in 1804,[k] after which he was manacled along with Tsukimaro, Toyokuni, Shuntei, Shun'ei, and Jippensha Ikku for fifty days and their publishers subjected to heavy fines.[9] Utamaro is known primarily for his bijin-ga portraits of female beauties, though his work ranges from kachō-e "flower-and-bird pictures" to landscapes to book illustrations.[34] Utamaro experimented with line, colour, and printing techniques to bring out subtle differences in the features, expressions, and backdrops of subjects from a wide variety of class and background.His sensuous beauties generally are considered the finest and most evocative bijinga in all of ukiyo-e.[37] He succeeded in capturing the subtle aspects of personality and the transient moods of women of all classes, ages, and circumstances.[49] The painter character Seiji Moriyama in the British novelist Kazuo Ishiguro's An Artist of the Floating World (1986) has a reputation as a "modern Utamaro" for his combination of Western techniques Utamaro-like feminine subjects.The only surviving official record of Utamaro is a stele at Senkō-ji Temple, which gives his death date as the 20th day of the 9th month of the year Bunka, which equates to 31 October 1806.The book posited ukiyo-e as having evolved towards a late-18th-century golden age that began to decline with the advent of Utamaro,[54] which he condemned for his "gradual elongation of the figure, and an adoption of violent emotion and extravagant attitudes".[55] In his Chats on Japanese Prints of 1915, Arthur Davison Ficke concurred that with Utamaro ukiyo-e entered a period of exaggerated, manneristic decadence.[56] Laurence Binyon, the Keeper of Oriental Prints and Drawings at the British Museum, wrote an account in Painting in the Far East in 1908 that was similar to Fenollosa's, considering the 1790s a period of decline, but placing Utamaro amongst the masters.[57] He called Utamaro "one of the world's artists for the intrinsic qualities of his genius" and "the greatest of all the figure-designers" in ukiyo-e, with a "far greater resource of composition" than his peers and an "endless" capacity for "unexpected invention".

The Coiffure , drypoint and aquatint , c. 1890–91

Japanese namesurnameUkiyo-eJapaneseōkubi-eToyotomi HideyoshiImpressionistsEdo periodcourtesanskabukipleasure districtswoodblock printsKiyonagaShunshōKatsukawa schoolShunkōyakusha-eyama-ubaKintarōShamisenYoshiwaraKawagoeMusashi ProvinceSaitama PrefectureToriyama SekienKanō schoolJapanese paintingEishōsai ChōkieggplantshaikaiNakamura-zaTsutaya JūzaburōKitao ShigemasaKatsukawa ShunshōŌta NanpokibyōshikyōkashungaeroticaToyokunisamuraitheir crestsbunrakuShun'eiJippensha IkkudaimyōKatō KiyomasaIshida MitsunariDaigo-jiposthumous nameTsukimaroWoldemar von Seidlitzbijin-gakachō-ebody proportionssurimonoMary CassattThe CoiffuredrypointaquatintJaponismeSiegfried BingHokusaiHiroshigeGauguinToulouse-Lautrecshin-hangaGoyō HashiguchiTaishō periodKazuo IshiguroAn Artist of the Floating WorldFukaku Shinobu KoiPersona 5East Asian age reckoningUkiyo-e RuikōErnest FenollosaArthur Davison FickeLaurence BinyonBritish MuseumJames A. MichenerSukenobuSharakusumptuary lawsEdmond de GoncourtTadamasa HayashiJack HillierUtamakuraTen Types of Women's PhysiognomiesAnthology of Poems: The Love SectionFive Shades of Ink in the Northern QuarterTwelve Hours of the Green HousesRenowned Beauties from the Six Best HousesShinagawa no Tsuki, Yoshiwara no Hana, and Fukagawa no YukiThree Beauties of the Present DaySugatami Shichinin KeshōHari-shigotoTsuitate no DanjoJiji PressGlobal OrientalChazen Museum of ArtGreenwood Publishing GroupStanford University PressBritish Association for Japanese StudiesMetropolitan Museum of ArtShueishaFairleigh Dickinson Univ PressKodanshaKodansha InternationalLane, RichardDoubledayManchester University PressMichener, James AlbertUniversity of Hawaii PressTuttle PublishingThe StudioUniversity of Hawai'i PressWikisource1911 Encyclopædia BritannicaFujin Sōgaku Jittai and Fujo Ninsō JuppinKasen Koi no BuSeirō JūnitokiHokkoku Goshiki-zumiKasumi-ori Musume HinagataKōmei Bijin RokkasenFujin Tomari-kyaku no ZuOn Top and Beneath Ryōgoku Bridge