Tornadogenesis

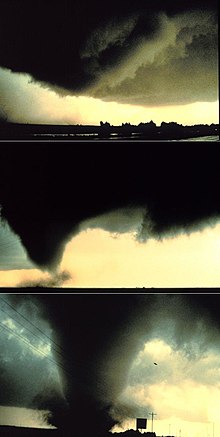

Despite ongoing scientific study and high-profile research projects such as VORTEX, tornadogenesis is a volatile process and the intricacies of many of the mechanisms of tornado formation are still poorly understood.[4] The process by which a tornado dissipates or decays, occasionally conjured as tornadolysis, is of particular interest for study as is tornadogenesis, longevity, and intensity.As rainfall in the storm increases, it drags with it an area of quickly descending air known as the rear flank downdraft (RFD).As the funnel descends, the RFD also reaches the ground, creating a gust front that can cause severe damage a good distance from the tornado.[6] Field studies have shown that in order for a supercell to produce a tornado, the RFD needs to be no more than a few kelvin cooler than the updraft.Tornadoes sometimes form from mesovortices within squall lines (QLCS, quasi-linear convective systems), most often in middle latitudes regions.

supercellularwall cloudfunnel cloudFalcon, ColoradoTornado AlleytornadoVORTEXcumuliformcloud basevorticityintensitythunderstormmesocyclonerear flank downdrafthelicityinflowMisoscale meteorologyWaterspoutmoisturewind shearland breezeslake effectLandspoutboundary layersquall linesmiddle latitudesFire whirlpyrocumulonimbiCyclogenesisConvective storm detectionBibcodeMarkowski, Paul M.Davies-Jones, RobertMarkowski, PaulRasmussen, Erik