Rædwald of East Anglia

Details about Rædwald's reign are scarce, primarily because the Viking invasions of the 9th century destroyed the monasteries in East Anglia where many documents would have been kept.A smaller ship-burial was also discovered in 1998 close to the original Sutton Hoo site, which is thought to have contained the body of his son Rægenhere, who died in battle in 616.The historian Barbara Yorke argues that East Anglia almost certainly produced a similar range of written materials, but they were destroyed during the Viking conquest in the 9th century.[5] The earliest and most substantial source for Rædwald is the Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People), completed in 731 by Bede, a Northumbrian monk.[9] The Battle of the River Idle, in which Rædwald and his forces defeated the Northumbrians, is described in the 12th century Historia Anglorum, written by Henry of Huntingdon.[15][16] The Bernician dynasty, allied by kinship to the kingdom of Wessex, gained ascendancy over Deira, forcing Edwin to live in exile in the court of Cadfan ap Iago of Gwynedd.Events that occurred during the early years of Rædwald's reign include the arrival of Augustine of Canterbury and his mission from Rome in 597, the conversions of Æthelberht of Kent and Saeberht of Essex, and the establishment of new bishoprics in their kingdoms.[26] Barbara Yorke argues that Rædwald was not willing to fully embrace Christianity because conversion via Æthelberht would have been acknowledgment of an inferior status to the Kentish king.If, as is supposed by some, Paulinus appeared to him in the flesh, the bishop's presence at Rædwald's court would throw some light on the king's position regarding religion.[32] Rædwald's pagan queen admonished him for acting in a manner dishonourable for a king by betraying his trust for the sake of money and wanting to sell his imperiled friend in exchange for riches.Kirby has argued that the battle was more than a clash between two kings over the treatment of an exiled nobleman but was "part of a protracted struggle to determine the military and political leadership of the Anglian peoples" at that time.After the death of the Christian Saebert of Essex, his three sons shared the kingdom, returning it to pagan rule, and drove out the Gregorian missionaries led by Mellitus.[44] His death is recorded twice by Roger of Wendover, in 599 and in 624, in a history that dates from the 13th century but appears to include earlier annals of unknown origin and reliability.In the centre of the ship was a chamber containing a collection of jewellery and other rich grave goods, including silver bowls, drinking vessels, clothing and weaponry.The gold and garnet body-equipment found with the other goods was produced for a patron who employed a goldsmith the equal or better than any in Europe and was designed to project an image of imperial power.[49] Yorke suggests that the treasures buried with the ship reflect the size of the tribute paid to Rædwald by subject kings during his period as bretwalda.[57] Swedish cultural influence has been detected at Sutton Hoo: there are strong similarities in both the armour and the burial with Vendel Period finds from Sweden.[58] There are also significant differences, and exact parallels with the workmanship and style of the Sutton Hoo artefacts cannot be found elsewhere; as a result the connection is generally regarded as unproven.[59][60] It is also possible that the mound is actually a cenotaph rather than a grave,[61] the only sign of body being a chemical stain which could have had other origins; indeed, the site includes burials of both meat and companion animals.

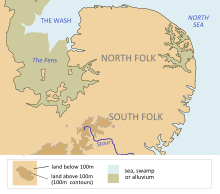

BretwaldaSutton Hoo helmetKing of the East AnglesTytilaEorpwaldSutton HooEorpwald of East AngliaDynastyWuffingasTytila of East AngliaOld Englishking of East AngliaAnglo-SaxonNorfolkSuffolkEast AnglesVikingmonasteriesÆthelberht of KentBattle of the River IdleÆthelfrith of NorthumbriaNorthumbriaHumber estuaryAnglo-Saxon Chroniclebecome a ChristianapostasyEnglishBarbara YorkeHistoria ecclesiastica gentis AnglorumGregorian missionEdwin of NorthumbriachroniclersRoger of WendoverannalisticAnglian collectionSt Gregory the GreatWhitbyRiver IdleHenry of HuntingdonAnglesSaxonsFrisiansBerctaFrankishCharibert ICeawlin of WessexMerciaCreodaBerniciaWessexCadfan ap IagoGwyneddÆthelfrith of BerniciaNorthumbrianSigeberhtEast Saxon dynastyWilliam of Malmesburykingdom of the East AnglesAugustine of CanterburymissionsacramentsEaldwulf of East AngliaRendleshamOswaldCearl of MerciaPaulinus of Yorkkingdom of LindseyD.P. KirbybretwaldasEadbaldSaebert of EssexMellitusquayside settlementIpswichNorth SeacemeteryRhinelandBritish MuseumbarrowsWoodbridge, SuffolkRiver DebensceptrewhetstonegoldsmithRupert Bruce-MitfordOxford Dictionary of National BiographySwedishVendel PeriodcenotaphEast Angliapublic domainChisholm, HughEncyclopædia BritannicaWayback MachineDictionary of National BiographyInternet ArchiveBruce-Mitford, RupertBruce-Mitford, R.L.S.Dumville, D.Cambridge University PressHunt, WilliamLee, SidneyStenton, F.M.Yorke, BarbaraProsopography of Anglo-Saxon EnglandEnglish royaltyTyttlaMonarchs of East AngliaRicberhtEcgricÆthelhereÆthelwoldEaldwulfÆlfwaldBeonnaAlberhtÆthelred IÆthelberht IIEadwaldCœnwulfCeolwulfBeornwulfÆthelstanÆthelweardEdmund the MartyrÆthelred II