Prospect theory

The theory describes the decision processes in two stages:[1] The formula that Kahneman and Tversky assume for the evaluation phase is (in its simplest form) given by: whereThe fourth item states expected attitudes of a potential defendant and plaintiff in discussions of settling a civil suit.This bias can lead to seemingly poorer decision making, as individuals may focus towards avoiding immediate losses instead of achieving long-term gains.Overall, the study by Gneezy and Potters emphasizes the existence of myopic loss aversion, demonstrating how this bias can result in non-optimal decisions.By analyzing how prospect theory and myopic loss aversion influence decision-making, it provides the ability for researchers and policymakers to create interventions that help people make more informed choices and attain their long-term goals.[1] Studies in behavioral finance analyzed this pattern, observing that there is a tendency to avoid high-reward options in the market, as the risk of short-term loss potentially influences the broker.This puzzle refers to the fact that stocks, in terms of historical statistics, exceed profits in comparison to bonds over extended periods of time.This behavior can lead to a decreases market predictability, as investors act on short-term losses by selling their stocks, there can be a ripple effect that intensifies dips in the economy.As investors that are heavily influenced by the market decline sell their stocks, the now increased amount of shares due to mass sell-offs further lower prices.An example of this effect was seen during economic crises such as the 2008 financial crash, when panic induced sell-offs heavily impacted market stability.An important implication of prospect theory is that the way economic agents subjectively frame an outcome or transaction in their mind affects the utility they expect or receive.Narrow framing is a derivative result which has been documented in experimental settings by Tversky and Kahneman,[6] whereby people evaluate new gambles in isolation, ignoring other relevant risks.Previous attempts at predicting consumer behavior have shown that utility theory does not sufficiently describe decision making under risk.The greater accuracy may be explained by the new model having the ability to correct for two behavioral irrationalities: The sunk cost fallacy and average auctioneer revenues above current retail price.[14] Both rational choice and game theoretical models generate significant predictive power in the analysis of politics and international relations (IR).But prospect theory, unlike the alternative models, (1) is "founded on empirical data", (2) allows and accounts for dynamic change, (3) addresses previously-ignored modular elements, (4) emphasizes the situation in the decision-making process, (5) "provides a micro-foundational basis for the explanation of larger phenomena", and (6) stresses the importance of loss in utility and value calculations.For example, they have found that politicians are more likely to phrase a radical economic policy as one ensuring 90% employment rather than 10% unemployment, because framing it as the former puts the citizenry in a "domain of gain," which is thereby conducive to greater populace satisfaction."[T]he disutility induced by loss aversion," even with minute probabilities of said insurrection, will dissuade the government from moving forward with the reform.[17] Barbara Vis and Kees van Kersbergen have reached a similar conclusion in their investigation of Italian welfare reforms.[18] Maria Fanis uses prospect theory to show how risk acceptance can help domestic groups overcome collective action problems inherent to coalition building.[19] Zeynep Somer-Topcu's research suggests that political parties respond more strongly to electoral defeat than to success in the next election cycle.[21] International relations theorists have applied prospect theory to a wide range of issues in world politics, especially security-related matters.[22][16] For example, in war-time, policy-makers, when in a perceived domain of loss, are more likely to take risks that would otherwise have been avoided, e.g. "gambling on a risky rescue mission", or implementing radical domestic reform to support military efforts.They developed detailed qualitative case studies of specific foreign policy decisions to explore the role of framing effects in choice selection.[23] Jeffrey Berejikian employed prospect theory to analyze the genesis of the Montreal Protocol, a landmark environmental agreement.[24] William Boettcher integrated elements of prospect theory with psychological research on personality dispositions to construct a “Risk Explanation Framework,” which he used to analyze foreign-policy decision making.Syndor (2010) suggests that the probability weighting aspect of prospect theory aims to explain the behaviour of the consumers who choose a higher premium for a reduced deductible even when the annualised claim rate is very low (approximately 5%).This is essentially the premise that expectations and context have a large impact on determining the reference point and therefore the perception of “gains” and “losses”.[11] Some critics have charged that while prospect theory seeks to predict what people choose, it does not adequately describe the actual process of decision-making.For example, Nathan Berg and Gerd Gigerenzer claim that neither classical economics nor prospect theory provide a convincing explanation of how people actually make decisions.

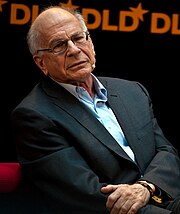

Daniel KahnemanNobel Memorial Prize in Economicsbehavioral economicsAmos Tverskycontrolled studiesindividualsloss aversionexpected utility theoryrational agentsbehaviorlotteryJohn von NeumannOskar Morgensternexperimental methodsRichard Thalerasymmetricalrisk averseconcaverisk seekingconvexmarginal utilitycognitive biasoverconfidence effectheuristicframing effectsutilitylineardominatesdisposition effectrisk aversionmental accountingdigital ageequity premium puzzlestatus quo biasintertemporal consumptionendowment effectauctionspsychologicalrational choicegame theoreticalinternational relationswar-timeRose McDermottSuez CrisisU-2 CrisisMontreal Protocolconsumer choicesstochastic dominanceintransitivitycumulative prospect theoryrank-dependent expected utilityreal numberpriority heuristicTheory and DecisionNature Human BehaviourDecision theoryDescription-experience gapMinimaxThe Paradox of ChoiceThinking, Fast and SlowTOTREPUltimatum gameCiteSeerXBaron, JonathanEasterlin, Richard A.Frank, Robert H.Kahneman, DanielTversky, Amos