Persian carpet

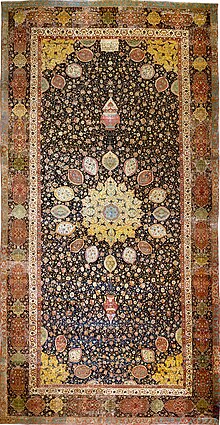

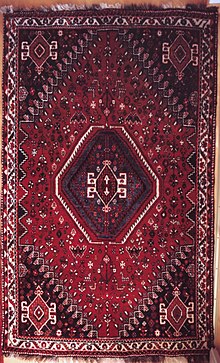

Persian rugs and carpets of various types were woven in parallel by nomadic tribes in village and town workshops, and by royal court manufactories alike.The carpets woven in the Safavid court manufactories of Isfahan during the sixteenth century are famous for their elaborate colours and artistic design, and are treasured in museums and private collections all over the world today.Their patterns and designs have set an artistic tradition for court manufactories which was kept alive during the entire duration of the Persian Empire up to the last royal dynasty of Iran.Carpets woven in towns and regional centers like Tabriz, Kerman, Ravar, Neyshabour, Mashhad, Kashan, Isfahan, Nain and Qom are characterized by their specific weaving techniques and use of high-quality materials, colours and patterns.Hand-woven Persian rugs and carpets have been regarded as objects of high artistic and utilitarian value and prestige since the first time they were mentioned by ancient Greek writers.Flat-woven kilims dating to at least the fourth or fifth century AD were found in Turfan, Hotan prefecture, East Turkestan, China, an area which still produces carpets today.[17] A Turkish carpet pattern depicted on Jan van Eyck's "Paele Madonna" painting was traced back to late Roman origins and related to early Islamic floor mosaics found in the Umayyad palace of Khirbat al-Mafjar.[19] More of these textiles were preserved in Tibetan monasteries, and were removed by monks fleeing to Nepal during the Chinese cultural revolution, or excavated from burial sites like Astana, on the Silk Road near Turfan.The high artistic level reached by Persian weavers is further exemplified by the report of the historian Al-Tabari about the Spring of Khosrow carpet, taken as booty by the Arabian conquerors of Ctesiphon in 637 AD.[20][21] Fragments of pile rugs from findspots in north-eastern Afghanistan, reportedly originating from the province of Samangan, have been carbon-14 dated to a time span from the turn of the second century to the early Sasanian period.Among these fragments, some show depictions of animals, like various stags (sometimes arranged in a procession, recalling the design of the Pazyryk carpet) or a winged mythical creature.Wool is used for warp, weft, and pile, the yarn is crudely spun, and the fragments are woven with the asymmetric knot associated with Persian and far-eastern carpets.The great Arabian traveller Ibn Battuta mentions that a green rug was spread before him when he visited the winter quarter of the Bakhthiari atabeg in Idhej.[31] Timurid period miniatures show carpets with geometrical designs, rows of octagons and stars, knot forms, and borders sometimes derived from kufic script.Large spirals and tendrils, floral ornaments, depictions of flowers and animals, were often mirrored along the long or short axis of the carpet to obtain harmony and rhythm.[36] Representative Safavid carpets made of silk with inwoven gold and silver threads were erroneously believed by Western art historians to be of Polish manufacture.In 1722, Peter the Great launched the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of Iran's Caucasian territories, including Derbent, Shaki, Baku, but also Gilan, Mazandaran and Astrabad.The centuries-old traditions of nomadic carpet weaving, which had entered a process of decline with the introduction of synthetic dyes and commercial designs in the late nineteenth century, were almost annihilated by the politics of the last Iranian imperial dynasty.Its characteristics and quality vary from each area to the next, depending on the breed of sheep, climatic conditions, pasturage, and the particular customs relating to when and how the wool is shorn and processed.This often results in faster pile wear in areas dyed in dark brown colours, and may create a relief effect in antique oriental carpets.Its occurrence suggests that a single weaver has likely woven the carpet, who did not have enough time or resources to prepare a sufficient quantity of dyed yarn to complete the rug.The main fields of Persian rugs are frequently filled with redundant, interwoven ornaments, often in form of elaborate spirals and tendrils in a manner called infinite repeat.Single design elements can also be arranged in groups, forming a more complex pattern:[25][34] Persian carpets are best classified by the social context of their weavers.However, during the twentieth century, the nomadic lifestyle was changed to a more sedentary way either voluntarily, or by the forced settlement policy of the last Persian emperors of the Pahlavi dynasty.They speak a Turkic dialect similar to that of Azerbaijan, and may have migrated to the Fars province from the north during the thirteenth century, possibly driven by the Mongol invasion.[60] As the truly nomadic way of life has virtually come to an end during the twentieth century, most Qashqai rugs are now woven in villages, using vertical looms, cotton warps, or even an all-cotton foundation.[57] The Afshar people are a semi-nomadic group of Turkic origin, principally located in the mountainous areas surrounding the modern city of Kerman in southeastern Iran.They produce mainly rugs in runner formats, and bags and other household items with rectilinear or curvilinear designs, showing both central medallions and allover patterns.Bakshaish carpets with a shield-shaped large medallion, less elaborate rectilinear patterns in salmon red and blue are labeled after the village of Bakhshayesh.[50] Major production centers in the West are Hamadan, Saruk with its neighbouring town of Arak, Minudasht also known under the trade name Lilihan and Serabend, Maslaghan, Malayer and Feraghan.

SafavidLouvreMuseo Poldi PezzoliMuseum für Kunst und Gewerbe HamburgKermanPersianromanizedPersiaPersian cultureIranian artOriental rugsroyal courthistory of IranIsfahanTabrizNeyshabourMashhadKashanGabbehnatural dyesancient GreekSoumakSuzaniFars provinceUNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Listswarp and weftpile rugthreadHermitage MuseumPazyrykScythianAltai MountainsSiberiaknots perSergei RudenkoAchaemenidsOdysseyPliny the Eldernat. VIII, 48kilimsTurfanHotan prefectureLop NurDura-EuroposXenophonAnabasisflat-weavingembroideryAchaemenianSeleucidParthianSasanian EmpireParthian EmpireByzantine EmpireCtesiphonZoroastrianismAnatoliaAntiochJan van Eyck"Paele Madonna"Khirbat al-MafjarChinese cultural revolutionSilk RoadAl-TabariSpring of KhosrowAfghanistanSamanganAl-SabahDar al-Athar al-IslamiyyahMuslim conquest of PersiaCaliphatesHudud al-'AlamAl-MuqaddasiYaqut al-HamawiAzerbaijānIbn BattutaatabegAbbasid CaliphateSiege of Baghdad (1258)Mongol EmpireHulagu KhanMamlukOttomanconquest of EgyptTurkish carpetSeljuqTurko-Persian traditionAlâeddin MosqueEşrefoğlu MosqueBeyşehirFostatBeysehirMongols"Ilkhan"GhazanTimurid Empire"White Sheep" TurkmenUzun HassanOttoman–Venetian War (1463–1479)Giosafat BarbaroRuy González de ClavijoHenry III of CastileSamarkandMuseum of Islamic Art, DohaArdabil CarpetIsmail IShi'a IslamTahmasp IAbbas ISafavid artOttoman–Safavid War (1603–18)Safavid dynastyPersian artminiature paintingsIslamic calligraphyHolbein carpetsarabesquesKurt ErdmannKamāl ud-Dīn BehzādArdabil carpetsSafi-ad-din ArdabiliArdabilCarlo CaliariMarino GrimaniSigismund III VasaVictoria and Albert Museum