Maclura pomifera

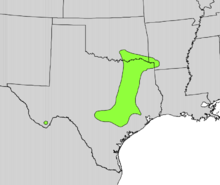

Maclura pomifera, commonly known as the Osage orange (/ˈoʊseɪdʒ/ OH-sayj), is a small deciduous tree or large shrub, native to the south-central United States.In 1810, Bradbury relates that he found two Maclura pomifera trees growing in the garden of Pierre Chouteau, one of the first settlers of Saint Louis, apparently the same person.[18] The trees were named bois d'arc ("bow-wood")[6] by early French settlers who observed the wood being used for war clubs and bow-making by Native Americans.[14] Meriwether Lewis was told that the people of the Osage Nation, "So much ... esteem the wood of this tree for the purpose of making their bows, that they travel many hundreds of miles in quest of it.Some historians believe that the high value this wood had to Native Americans throughout North America for the making of bows, along with its small natural range, contributed to the great wealth of the Spiroan Mississippian culture that controlled all the land in which these trees grew.Staminate flowers are pale green, small, and arranged in racemes borne on long, slender, drooping peduncles developed from the axils of crowded leaves on the spur-like branchlets of the previous year.Pistillate flowers are borne in a dense spherical many-flowered head which appears on a short stout peduncle from the axils of the current year's growth.[23] Osage orange's pre-Columbian range was largely restricted to a small area in what is now the United States, namely the Red River drainage of Oklahoma, Texas, and Arkansas, as well as the Blackland Prairies and post oak savannas.[24] The largest known Osage orange tree is located at the Patrick Henry National Memorial, in Brookneal, Virginia, and is believed to be almost 350 years old.[28] Because of the limited original range and lack of obvious effective means of propagation, the Osage orange has been the subject of controversial claims by some authors to be an evolutionary anachronism, whereby one or more now extinct Pleistocene megafauna, such as ground sloths, mammoths, mastodons or gomphotheres, fed on the fruit and aided in seed dispersal.[21][29] An equine species that became extinct at the same time also has been suggested as the plant's original dispersal agent because modern horses and other livestock will sometimes eat the fruit.[10] The fruit is not poisonous to humans or livestock, but is not preferred by them,[31] because it is mostly inedible due to a large size (about the diameter of a softball) and hard, dry texture.[6] John Bradbury, a Scottish botanist who had traveled the interior United States extensively in the early 19th century, reported that a bow made of Osage timber could be traded for a horse and a blanket.Palmer and Fowler's Fieldbook of Natural History 2nd edition rates Osage orange wood as being at least twice as hard and strong as white oak (Quercus alba).[31][48][49] In 2004, the EPA insisted that a website selling M. pomifera fruits online remove any mention of their supposed repellent properties as false advertising.

Bois d'arc (disambiguation)multiple fruitConservation statusLeast ConcernIUCN 3.1NatureServeScientific classificationPlantaeTracheophytesAngiospermsEudicotsRosidsRosalesMoraceaeMacluraBinomial nameSynonymsdeciduousorangemulberryforagingDaniel H. JanzenPaul S. Martinevolutionary anachronismcommon namesWilliam DunbarMississippi RiverOuachita RiverMeriwether LewisPresident JeffersonOsage NationSaint LouisPierre ChouteauAmerican settlersadventitious shootsbarbed wireFrenchNative AmericansComancheComancheríaSpiroan Mississippian cultureWilliam MaclureOsage Native Americansultraviolet lightspecific gravityarranged alternatelysimpleleaf axilsBranchletspistillatestaminateracemespedunclesOvariesorange (the fruit)tuberculatedsyncarpdrupescarpelscucumberRed RiverOklahomaArkansasBlackland Prairiespost oak savannasChisos MountainsPatrick Henry National MemorialBrookneal, VirginiaFort HarrodHarrodsburg, KentuckyPleistocene megafaunaground slothsmammothsmastodonsgomphotheresequinejust-so storysoftballsquirrelslivestockCrossbillsLoggerhead shrikescoppicingYugoslaviaRomaniaOsajinpomiferinisoflavonespectinfelledwindbreakFranklin Delano RooseveltGreat Plains ShelterbeltshelterbeltsChestertown, MarylandHMS SultanatreenailsJohn Bradburyfusticanilineheating valueQuercus albadecoctiontopicallyIUCN Red List of Threatened SpeciesBibcodeGermplasm Resources Information NetworkAgricultural Research ServiceUnited States Department of AgricultureWayback MachineArnoldiaWashington, D.C.United States Forest ServicePeattie, Donald CulrossBonanza BooksEconomic BotanyThe PantagraphUniversity of Nebraska LincolnUniversity of IllinoisWikidataWikispeciesiNaturalistMoBotPFNSWFloraObservation.orgOpen Tree of Life